Before “Deregulation” (and Social Media), Radio-TV Jobs were Prized Catches.

“So, you want to be a radio star?” That question echoed a lot through our ears back in the day.

Few of us went into radio thinking we’d get rich. (Well, maybe some did.) Radio was fun and had a way of growing on you. It was a time when radio-TV careers got more respect. There was higher professional satisfaction – greater chances to show your skills and abilities. And there was certainly something special about the coordination and mixing of different sound sources with the human voice in reaching out to a listening audience.

Few of us went into radio thinking we’d get rich. (Well, maybe some did.) Radio was fun and had a way of growing on you. It was a time when radio-TV careers got more respect. There was higher professional satisfaction – greater chances to show your skills and abilities. And there was certainly something special about the coordination and mixing of different sound sources with the human voice in reaching out to a listening audience.

As most radio veterans will recall, that first job meant getting your foot in the door – probably lots of hours watching to learn how it was done at a local radio station. You also needed hands-on practice and experience, and some kind of training credentials. For some, it meant pursuing college or university studies in broadcasting, journalism (for those seeking more than DJ skills), or some related field. There were a number of solid university-based broadcasting schools providing broader communications opportunities.

As most radio veterans will recall, that first job meant getting your foot in the door – probably lots of hours watching to learn how it was done at a local radio station. You also needed hands-on practice and experience, and some kind of training credentials. For some, it meant pursuing college or university studies in broadcasting, journalism (for those seeking more than DJ skills), or some related field. There were a number of solid university-based broadcasting schools providing broader communications opportunities.

But for many, the four-year college path was too much classroom theory time which could better be spent in hands-on training in the studio or control room.

But for many, the four-year college path was too much classroom theory time which could better be spent in hands-on training in the studio or control room.

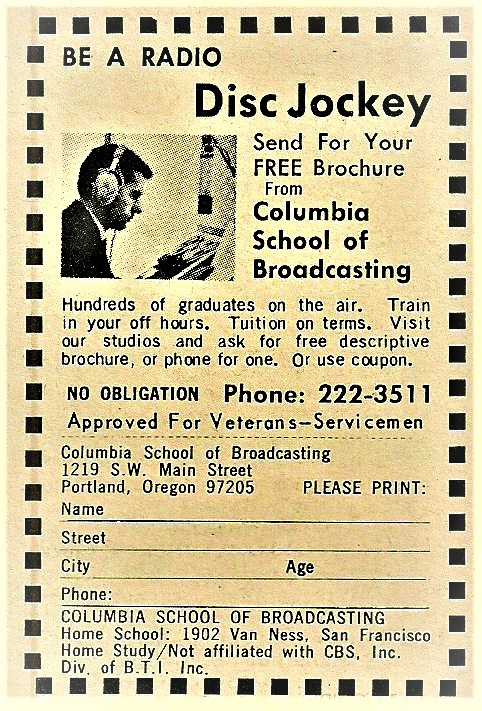

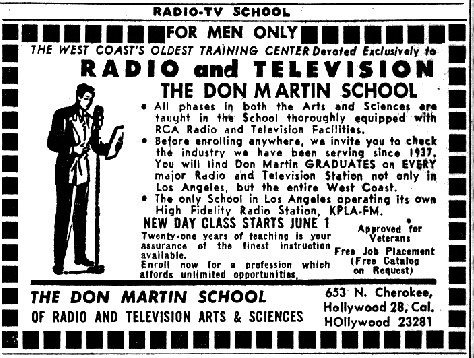

Voila! Enter the growing success of three-to-eight-month “ticket punch” schools – many gaining popularity in the 1950s and 1960s. A couple of them – the Don Martin School and Columbia School of Broadcasting – produced a number of big-name broadcast stars. Martin, based in Hollywood, trained (The Real) Don Steele, Don Imus and Bob Eubanks, plus Andy Barber, whose career took him to Spokane, Seattle and on to several big market gigs. Columbia, with schools across the country, claimed over 25,000 graduates since 1964.

Voila! Enter the growing success of three-to-eight-month “ticket punch” schools – many gaining popularity in the 1950s and 1960s. A couple of them – the Don Martin School and Columbia School of Broadcasting – produced a number of big-name broadcast stars. Martin, based in Hollywood, trained (The Real) Don Steele, Don Imus and Bob Eubanks, plus Andy Barber, whose career took him to Spokane, Seattle and on to several big market gigs. Columbia, with schools across the country, claimed over 25,000 graduates since 1964.

A graduation certificate from those ’50s and ’60s broadcasting schools was really a by-product for the time and money invested. More important, the schools provided the knowledge and know-how to pass the FCC’s First Class Radio Telephone Operator License exam – which many broadcast owners once required as a condition of employment.

Most non-technical on-air radio staffers were able to side-step that First phone need by getting an easily obtainable FCC Third Class License, allowing them to record technical meter readings, plus – with a simple short written test – a “broadcast endorsement” stamp permitting them to be a sole station operator at any time on the broadcast clock. (The Third Class License and endorsement was only applicable at non-directional radio stations and most directional AMs required operator’s with the First Class License.) In the so-called spirit of what became known as broadcast “deregulation,” the FCC further eased Third Class License requirements (in 1980) and suspended test exams for First Class Licenses and created the new General Class License (in 1982).

That’s not all that changed with “deregulation.” More on that after a bit more history . . . With broadcasting’s growth and success came demands for more hands-on training. To no one’s surprise, a number of radio personalities launched namesake schools, such as Ron Bailie and Paul Oscar Anderson (Paul E. Brown). Both carved solid 1960s footprints, Bailie at Seattle’s KJR and KOL, Anderson in several markets,including Portland and briefly in Seattle (KOL). He had been an on and off jock for Don Burden’s famed Star Stations. It’s believed Anderson was one of the disgruntled guys who brought down the Burden radio empire (read “Don Burden – Radio Stardom, Stormy End” by clicking here.)

Anderson’s Portland radio school wasn’t a big success. Bailie’s, on the other hand, grew beyond Seattle to five other locations – Spokane, Phoenix, Denver, San Francisco and San Jose. Between 1963 and 1990, Bailie’s schools enrolled more than 17,000 students.

Anderson’s Portland radio school wasn’t a big success. Bailie’s, on the other hand, grew beyond Seattle to five other locations – Spokane, Phoenix, Denver, San Francisco and San Jose. Between 1963 and 1990, Bailie’s schools enrolled more than 17,000 students.

Here’s a Bailie School radio commercial, which got airplay in all six markets, and more — until the Bailie boom went bust in the late 1980s.

Ron Bailie School Radio Ad :57

More than a Wrist-Slap

Although Bailie’s training was highly regarded, his handling of some of the school’s finances was not. In 1995, Bailie, his wife and daughter each were convicted of embezzling some of their students’ Perkins Loan repayments. Bailie was sentenced to three years in prison and ordered to pay more than $700,000 in fines and restitution. His wife and daughter got over two-year sentences and were required to each

Although Bailie’s training was highly regarded, his handling of some of the school’s finances was not. In 1995, Bailie, his wife and daughter each were convicted of embezzling some of their students’ Perkins Loan repayments. Bailie was sentenced to three years in prison and ordered to pay more than $700,000 in fines and restitution. His wife and daughter got over two-year sentences and were required to each

pay over $200,000 in fines and restitution.

The Ron Bailie example notwithstanding, broadcast training advanced beyond 90-day ticket punch courses to meet radio-television specialty skill needs. Demands for only board-shift disc jockeys were changing because the business was changing, as reflected in revamped broadcast training school curriculam—often toward Associate Degree programs. Many broadcast schools today place heavier emphasis on apprenticeships and student intern programs, a training path even more valuable to students when existing on-campus radio/TV station operations are available.

The Ron Bailie example notwithstanding, broadcast training advanced beyond 90-day ticket punch courses to meet radio-television specialty skill needs. Demands for only board-shift disc jockeys were changing because the business was changing, as reflected in revamped broadcast training school curriculam—often toward Associate Degree programs. Many broadcast schools today place heavier emphasis on apprenticeships and student intern programs, a training path even more valuable to students when existing on-campus radio/TV station operations are available.

Among those who’ve progressed: Bates Technical College, which started with basic radio training elements as Tacoma’s original Vocational Technical School back in the 1940s. Today it boasts some of the Northwest’s larger numbers of on-air and behind-the-scenes broadcast alumni.

There’s been similar success at Bellevue College, and, until otherwise just recently announced, Oregon’s Mt. Hood Community College, which reportedly plans to drop its long-successful radio-TV program. (read “Mt. Hood Community College Drops Broadcast Course” by clicking here.)

The Mt. Hood CC announcement is yet another development in how things have dramatically changed, in part due to the negative side of broadcast deregulation and likely consequential economic realities at the Oregon school. For potentially interested future broadcasters, there are clearly diminished job/career incentives. Some would say NO INCENTIVES.

Like it or not, radio – particularly AM – is dying in the face of changing technology and the FCC’s notorious ignoring and abuse of the AM signal band (I’ll let the audio engineer types address that). AM has lost hundreds of stations, and probably ten times that many on-air employees over recent years. But fewer than a dozen mega-owners thrive while the on-air product (mostly FM) has declined into stagnation.

Like it or not, radio – particularly AM – is dying in the face of changing technology and the FCC’s notorious ignoring and abuse of the AM signal band (I’ll let the audio engineer types address that). AM has lost hundreds of stations, and probably ten times that many on-air employees over recent years. But fewer than a dozen mega-owners thrive while the on-air product (mostly FM) has declined into stagnation.

Here’s Big Reason We Got into this Mess . . .

Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the start of the dismal state of what’s on your radio dial these days. The push for deregulation started 10 to 15 years before that because large company broadcast owners wanted a bigger piece of the radio industry with fewer restrictions.

Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the start of the dismal state of what’s on your radio dial these days. The push for deregulation started 10 to 15 years before that because large company broadcast owners wanted a bigger piece of the radio industry with fewer restrictions.

They pretty much got their way, despite glowing but unfounded arguments the changes would be the best for everyone. The act removed the cap on nationwide station ownerships and increased the number of stations one entity can own in a single market. In reality, America now has a small but elite ownership cartel that laps up about 90 percent of all radio broadcast revenue.

They pretty much got their way, despite glowing but unfounded arguments the changes would be the best for everyone. The act removed the cap on nationwide station ownerships and increased the number of stations one entity can own in a single market. In reality, America now has a small but elite ownership cartel that laps up about 90 percent of all radio broadcast revenue.

And that only begins to tell the story. Less competition has meant homogenized programming and limited news and information with fewer community-based points of view and less diversity in the needs of a broader range of American citizens. Corporate America’s mega-ownership broadcasting whims took over the industry and left little room for local ownerships or local creativity.

And that only begins to tell the story. Less competition has meant homogenized programming and limited news and information with fewer community-based points of view and less diversity in the needs of a broader range of American citizens. Corporate America’s mega-ownership broadcasting whims took over the industry and left little room for local ownerships or local creativity.

To many of us reading and relating to this issue, the biggest collateral damage is a fatal shot in the gut to successful radio’s critical element – the human professional communicator, whether called a deejay, announcer, host, narrator or moderator. The business clearly needs the quality skills of these people. We cannot expect broadcasting schools alone to change the course of things. But we can continue to look to those who have the best resources in apprenticing, mentoring and real-world training.

To many of us reading and relating to this issue, the biggest collateral damage is a fatal shot in the gut to successful radio’s critical element – the human professional communicator, whether called a deejay, announcer, host, narrator or moderator. The business clearly needs the quality skills of these people. We cannot expect broadcasting schools alone to change the course of things. But we can continue to look to those who have the best resources in apprenticing, mentoring and real-world training.

Does that mean better broadcasting schools and streamlined associate and bachelor’s degree programs? Perhaps, but with the caveat those broadcast curricula be more realistic, appealing and affordable. That, of course, leads to other issues and concerns that can’t be dealt with in the available space here.

Does that mean better broadcasting schools and streamlined associate and bachelor’s degree programs? Perhaps, but with the caveat those broadcast curricula be more realistic, appealing and affordable. That, of course, leads to other issues and concerns that can’t be dealt with in the available space here.

We’ve gone from the days of analog radio’s ticket-punch-talent to today’s far more complicated and politically challenging digital world. It’s not the first time people have considered radio on the ropes or near death. But most critical observers believe we have one—or maybe two—decades to find more balanced solutions to right the ship. Many think it rests with rekindling the kind of human touch skills that made radio the historic winner most of us remember.

Do we have the will or know-how to restock the talent tank drained by bottom line-conscious corporate suits who don’t know (or care?) what real broadcast success could be ?

What a great article, thank you! I am a 1972 Ron Bailie Seattle grad, and I got here via a link I encountered last night after I googled the name of the school just for old times sake. Imagine my surprise when the first link was to a Spokane newspaper article re the Bailie family’s prison sentences! My experience there was solid, in retrospect. I learned a lot, and ultimately got hired via the school’s referrals (WILD story on that subject). I “earned” my first class FCC license via rote memorization of hundreds of Q&As somehow obtained by the school. Our class was also trained in ad sales, which didn’t interest me at the time. Seattle AM radio dj’s were my heroes from the mid-60’s on, and the school changed my life by launching me on the then career of my dreams….long since abandoned, but what a ride! (Oh, and btw….one of our teachers was a co-founder of Starbucks….a then-risky venture he would talk about with us during class breaks!)

I look forward to further exploration of your website….and thanks again!