February 3, 1959 is the 60th anniversary of the plane crash deaths of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J. P. Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper. But aside from volumes written and mountains of grief expressed from the loss, less is understood about the hows, whys and the aftermath of that tragic Iowa disaster. News of the crash shocked both rock music fans and casual observers.

Plane crash radio news bulletin (Running time :23)

Holly, Valens and Richardson were killed, their bodies thrown from the V-tailed Beechcraft Bonanza (pilot Roger Peterson was found in the wreckage) near Mason City, Iowa. A critical look at circumstances which led to the fate of the victims reveals a string of bad timing, poor planning and ignored or missed dangers. The result: the 24-day mid-winter rock ‘n’ roll show called the “Winter Dance Party Tour” became a national nightmare.

The youthful clamor for late-’50s rock and roll was feeding the rising careers of Holly, Valens and Richardson. By the end of 1958, Holly had two top-five hits and four others in the Top 40. Valens scored two charted hits, including the ballad “Donna,” which pegged at #2 after his death. And D.J. the Big Bopper was known for a novelty style that propelled two of his songs into the top 40 within four months. An audio montage of the trio’s songs comes across as a cavalcade of late ’50s radio.

Holly, getting his Texas start at age 15, had singing potential that challenged Elvis. His songwriting and performing influence was hailed by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Elton John, Eric Clapton and others. His original Norm Petty-produced rockabilly material with the Crickets proved to be the pioneering template for the direction of American pop music for years to come. Valens, the young Latino phenom — among the first to get nationwide radio airplay — was a singer/songwriter and probably America’s first Chicano rock star. Richardson, the Beaumont, Texas deejay who boasted having 20 novelty songs ready for production, was a crowd pleaser. Within a few weeks of the Iowa tragedy, another deejay, Tommy Dee (at that time on KFXM, San Bernardino), produced the first pop music tribute. “Three Stars” peaked at #11 during an eight-week chart run in late March and April, 1959.

Holly, getting his Texas start at age 15, had singing potential that challenged Elvis. His songwriting and performing influence was hailed by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Elton John, Eric Clapton and others. His original Norm Petty-produced rockabilly material with the Crickets proved to be the pioneering template for the direction of American pop music for years to come. Valens, the young Latino phenom — among the first to get nationwide radio airplay — was a singer/songwriter and probably America’s first Chicano rock star. Richardson, the Beaumont, Texas deejay who boasted having 20 novelty songs ready for production, was a crowd pleaser. Within a few weeks of the Iowa tragedy, another deejay, Tommy Dee (at that time on KFXM, San Bernardino), produced the first pop music tribute. “Three Stars” peaked at #11 during an eight-week chart run in late March and April, 1959.

The Winter Dance Party Tour headliners were Holly, Valens, Richardson and Dion & the Belmonts. Other participants included drummer Carl Bunch and guitarist Tommy Allsup — Holly’s replacements for Jerry Allison and Joe Mauldin (Crickets), who Holly broke with a few months earlier. Holly’s tour also included Waylon Jennings — a Texas deejay and another promising singer/guitarist.

The Tour From Hell…

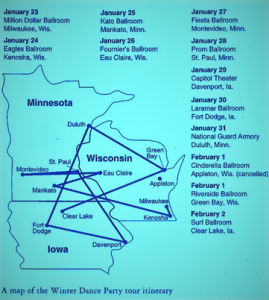

Problems with the Winter Dance Party Tour started weeks before its Jan. 23 opening in Milwaukee. It was to be 24 shows in 24 days at some of the country’s coldest cities in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky and Ohio. Winter weather conditions proved to be the tour’s undoing. The booking agency’s (General Artists Corp.) schedule didn’t account for the long distances and tough and dangerous winter road conditions. The original group of performers completed less than half the tour. The entire tour group traveled in a single bus. Due to frequent break-downs, they used three or four different (and UNHEATED) former school buses in the first (and final) 11 days.

It was slow going, sub-zero conditions and roads covered with ice and snow. The mood on the bus was pushed to anger, frustration and bitterness. The worst came after a cold and miserable Jan. 31 show in Duluth, Minnesota. En route overnight to Appleton, Wisconsin, the bus stalled in a snowbank near Ironwood, Michigan, requiring a local Sheriff’s Office rescue of the inadequately dressed and ill equipped musicians. Richardson and Valens complained of sickness and flu symptoms. Bunch was hospitalized with frostbitten feet. (That absence required other performers to trade off on drummer duties when not on the lead microphone). The Appleton show was cancelled and the group traveled by train to Green Bay. Buddy Holly historian Bill Griggs angrily blamed the booking agency’s poorly organized and zig-zag routing for turning those 11 days into “the tour from hell.” The tired, bewildered entourage finally completed the 350 miles from Green Bay to Clear Lake only hours before their Feb. 2 Surf Ballroom show. The performers had no inkling of the disaster yet to come.

It was slow going, sub-zero conditions and roads covered with ice and snow. The mood on the bus was pushed to anger, frustration and bitterness. The worst came after a cold and miserable Jan. 31 show in Duluth, Minnesota. En route overnight to Appleton, Wisconsin, the bus stalled in a snowbank near Ironwood, Michigan, requiring a local Sheriff’s Office rescue of the inadequately dressed and ill equipped musicians. Richardson and Valens complained of sickness and flu symptoms. Bunch was hospitalized with frostbitten feet. (That absence required other performers to trade off on drummer duties when not on the lead microphone). The Appleton show was cancelled and the group traveled by train to Green Bay. Buddy Holly historian Bill Griggs angrily blamed the booking agency’s poorly organized and zig-zag routing for turning those 11 days into “the tour from hell.” The tired, bewildered entourage finally completed the 350 miles from Green Bay to Clear Lake only hours before their Feb. 2 Surf Ballroom show. The performers had no inkling of the disaster yet to come.

The Clear Lake show at the historic Surf Ballroom was not on the original tour schedule, but it was added at the last-minute. After the stuck-in-the-Michigan-snow incident, Holly wanted to eliminate travel mishaps for the rest of the tour. He was concerned about the upcoming 365-mile trip north to Moorhead, Minnesota, and openly upset they would have to backtrack through towns they’d already played a week earlier. With frostbitten drummer Carl Bunch out and Richardson begging to avoid another long, uncomfortable bus ride, Holly chartered a plane to transport some of the musicians from Clear Lake to the Fargo airport.

The Clear Lake show at the historic Surf Ballroom was not on the original tour schedule, but it was added at the last-minute. After the stuck-in-the-Michigan-snow incident, Holly wanted to eliminate travel mishaps for the rest of the tour. He was concerned about the upcoming 365-mile trip north to Moorhead, Minnesota, and openly upset they would have to backtrack through towns they’d already played a week earlier. With frostbitten drummer Carl Bunch out and Richardson begging to avoid another long, uncomfortable bus ride, Holly chartered a plane to transport some of the musicians from Clear Lake to the Fargo airport.

Clear Lake, Iowa: The Final Show…

Bad Weather & Pilot Error…

Accounts differ as to how passengers were selected for the flight. But when the plane piloted by Roger Peterson took off after midnight Feb. 3, Holly, Richardson and Valens were on board. Holly was originally to be accompanied by Waylon Jennings and Dion DiMucci. But the two men gave up their seats — to learn later that their lives had been spared by a coin toss. These events changed the course of American music history. It was well after daylight when the remains of the overdue flight were discovered. Most damning were later investigation findings of the CAB (Civil Aeronautics Board, precursor of the Nat’l Transportation Safety Board).

Young pilot Peterson (age 21) unwisely agreed to the fly the plane, yet pre-dawn conditions were changing beyond his VFR (Visual Flight Rules) qualifications. Pilot inability to distinguish low clouds, visible horizons and ground lights weren’t factors during flight preparation, but those conditions became fatal upon takeoff. (Just before 1 a.m., takeoff time, the barometer was dropping and a snow squall was developing over the Mason City area). Peterson also was unfamiliar with the 1947 Beechcraft’s older style altitude gyroscope — which he mistakenly believed wouldn’t be a problem. The CAB cited pilot error and “spacial disorientation” as the primary reasons for the crash. Less than 10 minutes after becoming airborne, one of the plane’s wingtips hit the ground, cartwheeling the craft repeatedly over a 200-yard distance and throwing all three passengers from the aircraft. And lastly, CAB said, the pilot was not given adequate updated weather warnings before takeoff — a serious oversight on the part of Dwyer Flying Service, which managed the charter flight.

The Show Goes On…

In spite of the tragedy, the Winter Dance Party Tour continued as scheduled, with the 12th show the night of Feb. 3 in Moorehead, Minnesota. Waylon Jennings, Tommy Allsup and Dion & the Bellmonts took front stage for the three crash victims. That’s when Fargo native Bobby Vee got his first big stage start when show producers filled gaps in the lineup with local talent. Frostbitten Carl Bunch recovered in time to rejoin the tour on Feb. 4 in Sioux City, Iowa. Several days later there were Texas funerals for Holly and Richardson, a California service for Valens and an Iowa burial for Roger Peterson. Jennings, Allsup and Bunch pulled out of the last 11 tour engagements. The sad and infamous Winter Dance Party Tour finished on schedule February 15 in Springfield Illinois — but with a different playbill. Frankie Avalon, Jimmy Clanton and Fabian headlined the last two weeks, joined by two of Holly’s friends from the Crickets, Jerry Allison and Joe Mauldin. Despite the indescribable shock of the loss, memories of Valens and Richardson soon faded. But Holly’s better known stature in pop music has been lasting. His legacy, established in less than three years, gradually grew and was galvanized over the many years that followed. Unlike other musicians of the time, Holly doubled as one of the most prolific singers AND songwriters of early rock His smooth ballads and famous Holly “hiccup” were all over the radio in ’57-’58. Decca, Brunswick and Coral labels released dozens of Holly and the Crickets’ songs on 45 and 78 rpm records (34 were on the Hot 100, eight reached the top 10), plus three studio albums. But record executives had never before seen the kind of after-death record sales surge (especially in Europe) that Holly’s death created. The scramble for demo tapes, B-sides, alternate takes and other previously unheard material led to unprecedented stepped-up vinyl pressings and record releases. Perhaps most astounding is the 59-year run of 29 Holly compilation albums (three shown below), between 1959 and 2018, culminating with the November, 2018 “True Love Ways,” backed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

In spite of the tragedy, the Winter Dance Party Tour continued as scheduled, with the 12th show the night of Feb. 3 in Moorehead, Minnesota. Waylon Jennings, Tommy Allsup and Dion & the Bellmonts took front stage for the three crash victims. That’s when Fargo native Bobby Vee got his first big stage start when show producers filled gaps in the lineup with local talent. Frostbitten Carl Bunch recovered in time to rejoin the tour on Feb. 4 in Sioux City, Iowa. Several days later there were Texas funerals for Holly and Richardson, a California service for Valens and an Iowa burial for Roger Peterson. Jennings, Allsup and Bunch pulled out of the last 11 tour engagements. The sad and infamous Winter Dance Party Tour finished on schedule February 15 in Springfield Illinois — but with a different playbill. Frankie Avalon, Jimmy Clanton and Fabian headlined the last two weeks, joined by two of Holly’s friends from the Crickets, Jerry Allison and Joe Mauldin. Despite the indescribable shock of the loss, memories of Valens and Richardson soon faded. But Holly’s better known stature in pop music has been lasting. His legacy, established in less than three years, gradually grew and was galvanized over the many years that followed. Unlike other musicians of the time, Holly doubled as one of the most prolific singers AND songwriters of early rock His smooth ballads and famous Holly “hiccup” were all over the radio in ’57-’58. Decca, Brunswick and Coral labels released dozens of Holly and the Crickets’ songs on 45 and 78 rpm records (34 were on the Hot 100, eight reached the top 10), plus three studio albums. But record executives had never before seen the kind of after-death record sales surge (especially in Europe) that Holly’s death created. The scramble for demo tapes, B-sides, alternate takes and other previously unheard material led to unprecedented stepped-up vinyl pressings and record releases. Perhaps most astounding is the 59-year run of 29 Holly compilation albums (three shown below), between 1959 and 2018, culminating with the November, 2018 “True Love Ways,” backed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

Ten years after Holly’s death, MCA Records unveiled “Giant,” the eighth posthumous album, and the fifth to include previously unreleased material. Promoters called it Holly’s last “new” album, which created quite a buzz because of the production enhancements added to its lead song on Side A. “Love is Strange” (also released as a single) was written in the mid-’50s by rhythm & blues pioneer Bo Didley. Holly laid down the simple voice/guitar track the month before he died. But the studio recording was unreleased until instrumentation was added and then Coral Records pressed it. (Vocal duo Mickey & Sylvia rode the song to #11 on Billboard in early 1957). In the spring of 1969, Holly’s version received air play, although it didn’t chart in the top 40. Many people, who were not around when Holly died, were fascinated to learn how his final version of “Love is Strange” came to be.

Buddy Holly won numerous national/global awards, reflecting accomplishments before and after his death. Inducted into the Rock and Roll and Songwriters Halls of Fame in 1986 and the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999, Holly is ranked #13 on Rolling Stone Magazine’s list of 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.

Grieving Survivors…

Family and personal friends of the deceased were stricken by the fateful plane crash. Holly’s mother screamed and collapsed to the floor when she heard on the radio of her son’s death. Ironically, she later wrote a letter of sympathy to pilot Roger Peterson’s family — not to blame, but to comfort them in that shared time of sadness. Holly’s wife of six months, Maria Elena, also learned of the accident from a news broadcast. She was pregnant and claimed to suffer a miscarriage as a result of the overwhelming psychological trauma. Equally shocking was Maria’s decision to not attend her husband’s funeral. She was too distraught and blamed herself for Holly’s death — she said she should have been on the tour to stop him from getting on that airplane. The Holly party deaths, and other high-profile fatality incidents, led to new policies in which authorities withheld victims’ names until notification of next of kin. (A practice military sources and some news organizations said had actually been in place well before 1959).

Valens wrote the song “Donna” for his southern California high school sweetheart, Donna Ludwig. In a phone conversation in late 1958 he promised her he’d write the song. It was released the Christmas after his death and “Donna” became a huge national hit. At her father’s urging, Donna Ludwig later recorded a two-song tribute to Valens, which she said made her feel uncomfortable at the time. The songs (on one 45 rpm record),“Now that You’re Gone” and “Lost Without You,” received little air play and fell into obscurity. (The single eventually became a

Buddy Holly’s 1958 hit song “Peggy Sue” was based on a real person. Peggy Sue Gerron was Holly’s classmate and a close friend at Lubbock High School. When Holly wrote the original song he planned to title it “Cindy Lou.” But a fellow Cricket, Jerry Allison, convinced Buddy to change it because Allison wanted to impress Gerron. Allison and Gerron did marry (doing a double-couple honeymoon with Buddy and Maria Holly in 1958), but they divorced in the mid-1960s.

Don McLean’s giant 1971-’72 hit American Pie revived interest in “the day the music died.” Read that interesting story here.

Some comments may be held for moderation. (New users)