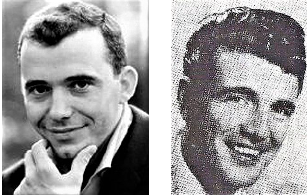

Within the archives of American pop music is the story of the guy who got credit for a huge hit song he didn’t sing. Although Bill Parsons (right) had his name on the 45 rpm record, it was Bobby Bare (left) who carried the song to within a guitar strum from #1 on pop music charts in early 1959.

The irony of the bizarre but true whose-on-first-story is that Parsons initially got the footlights and the glory while Bare was peelin’ potatoes in his Army greens. But Bare got the last laugh (though he held no grudge). His career took off and he eventually became world famous. The song, The All American Boy, was recorded by the then-unknown Bare, who eventually scored dozens of country and pop music hits during a highly successful lifetime career. But when the song got immediate radio air play back in December, 1958, Parsons and Bare were both unknowns. The All American Boy was a cleverly done talking blues parody about Elvis Presley’s upstart career getting short-circuited because of Uncle Sam’s Army draft. (In reality, Presley’s career hardly slowed, thanks to timely record releases by RCA Victor while Elvis was overseas. (See Holiday Greetings from Elvis, 1959.)

Here’s the famous mislabeled recording — Bare’s first hit song — which spent 16 weeks on both the Billboard and Cash Box Top 100 charts during the first four months of 1959. (Simply click on the record to listen to the song.)

The song peaked at #2 in early February, but was unable to surpass Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, The Platters’ huge record that owned the top spot for three straight weeks.

The song peaked at #2 in early February, but was unable to surpass Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, The Platters’ huge record that owned the top spot for three straight weeks.

The All American Boy got lots of airplay in the Seattle area, too.

Look closely and you’ll see the song riding at #18 on this KOL Top 40 survey from January 22, 1959, its third week on the chart after moving up from #29 the week before. Like the national Billboard and Cash Box charts, Bobby Bare’s hit climbed just short of the top spot on Seattle radio surveys in early February. KOL was the pop/rock leader in Seattle at that time, followed closely by KAYO and then KJR.

The Seattle market jocks spinning the records in those days? Ric Thomas, Chuck Ellsworth , Al Cummings and Art Simpson at KOL . . . Claude Brimm, Bob Fredericks, Ted Bell and Pat O’Day at KAYO. . . and Gil Henry, Dave Clark, Don Hedman and Bob Carmichael at KJR. (O’Day had just arrived at KAYO from Yakima, but Lan Roberts wasn’t yet at KOL. And KAYO was still four years from its switch to a country format.)

Neither Bobby Bare nor Bill Parsons toured Seattle when The All American Boy was running the charts. Bare did perform in Seattle in later years. But if you keep on reading, you’ll learn that Parsons’ career fizzled.

The U.S. Army certainly figured into events that led to the success of The All American Boy. While Parsons had just been discharged, Bare was drafted into the Army when the song was born.

The U.S. Army certainly figured into events that led to the success of The All American Boy. While Parsons had just been discharged, Bare was drafted into the Army when the song was born.

Bare wrote The All American Boy under the pen name Orville Lunsford. In November 1958, before his Army stint, Bare promised to help Parsons, a longtime friend, with some recording practice to help kick start his career. They hired some musicians and laid down a couple of tracks at a recording studio in Cincinnati. One was Parsons’ take on a song called Rubber Dolly, the other was Bare’s vocal of The All American Boy. Fraternity Records paid $500 for the master demos, liked Bare’s song and wanted to release it after several other labels rejected it. When the record was released, Fraternity put Parson’s name on it, perhaps because the label owners believed Bare was under contract with another record company.There’s another version of the story, that Bare didn’t want artist credit because the recording session was intended to help Parsons’ career, and that his own career was soon to be interrupted by the same Army entry steps Elvis Presley had taken nine months earlier.

Bare wrote The All American Boy under the pen name Orville Lunsford. In November 1958, before his Army stint, Bare promised to help Parsons, a longtime friend, with some recording practice to help kick start his career. They hired some musicians and laid down a couple of tracks at a recording studio in Cincinnati. One was Parsons’ take on a song called Rubber Dolly, the other was Bare’s vocal of The All American Boy. Fraternity Records paid $500 for the master demos, liked Bare’s song and wanted to release it after several other labels rejected it. When the record was released, Fraternity put Parson’s name on it, perhaps because the label owners believed Bare was under contract with another record company.There’s another version of the story, that Bare didn’t want artist credit because the recording session was intended to help Parsons’ career, and that his own career was soon to be interrupted by the same Army entry steps Elvis Presley had taken nine months earlier.

Don Powell was the Dayton, Ohio guitarist who backed Bare in the original recording session. He said Bare felt his rapidly approaching Army duty would prevent him from promoting and performing the song, which Powell’s group, “The All-American Boys,” was anxious to do when the record was released.

Parsons was allowed to take Bare’s place, which led to another interesting twist: While Bare was at Fort Knox, Kentucky, Powell said Parsons fronted the full backup group in performing The All American Boy at various clubs and auditoriums from Detroit to St. Louis. But Powell said it didn’t work. “We couldn’t pull it off because Bill simply was no Bobby Bare. Bobby had the magic ability to be at one with an audience. He was truly one of a kind.”

Parsons was allowed to take Bare’s place, which led to another interesting twist: While Bare was at Fort Knox, Kentucky, Powell said Parsons fronted the full backup group in performing The All American Boy at various clubs and auditoriums from Detroit to St. Louis. But Powell said it didn’t work. “We couldn’t pull it off because Bill simply was no Bobby Bare. Bobby had the magic ability to be at one with an audience. He was truly one of a kind.”

It was some time before the record label name-swap was revealed. Bare learned of the song’s quick climb up the charts while in basic training, and was stunned to learn radio jocks were raving about the song’s exciting new artist – Bill Parsons.

Parsons was soon lip syncing the record on American Bandstand and other TV and public appearances, about which Bare later recalled Parsons saying he was at first shocked and scared to death. “In the beginning Bill didn’t even know the song,” Bare said, “and can you image how hard it was to lip sync a talkin’ record?” It would be long after The All American Boy was off the charts, off the air and forgotten before Bare would get his lip syncing debut on Dick Clark’s national TV show.

Parsons was soon lip syncing the record on American Bandstand and other TV and public appearances, about which Bare later recalled Parsons saying he was at first shocked and scared to death. “In the beginning Bill didn’t even know the song,” Bare said, “and can you image how hard it was to lip sync a talkin’ record?” It would be long after The All American Boy was off the charts, off the air and forgotten before Bare would get his lip syncing debut on Dick Clark’s national TV show.

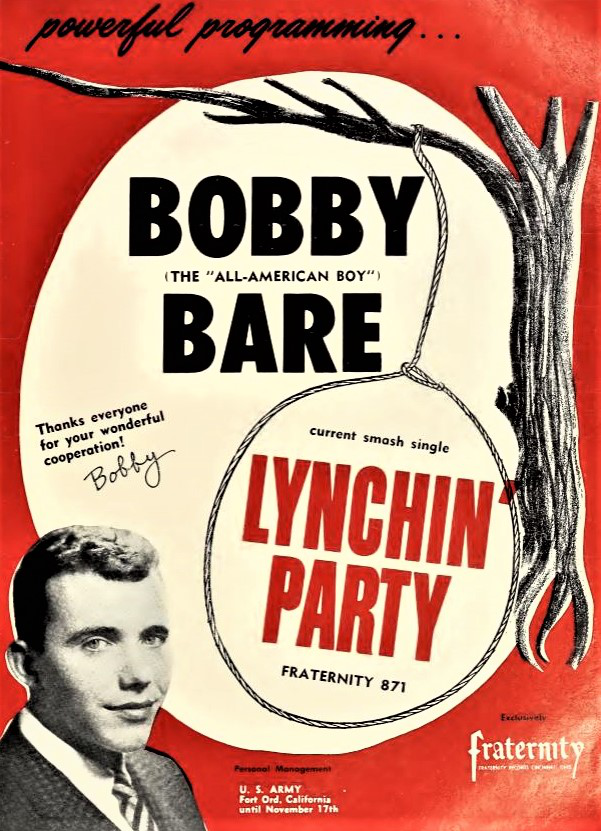

As The All American Boy was scaling the Hot 100, Fraternity began to release several correctly credited Bobby Bare sides, promoting them via Cash Box and Billboard Magazine ads.

As The All American Boy was scaling the Hot 100, Fraternity began to release several correctly credited Bobby Bare sides, promoting them via Cash Box and Billboard Magazine ads.

The same trade mags also included a Fraternity spread calling Parsons “a great new star on the horizon” (that’s buried in the fine print on the right photo) and introducing a quick followup song to The All American Boy. But music critics, who saw through it all, later said Educated Rock ‘n’ Roll, which was Bill Parsons’ second vocal release (Rubber Dolly, the B-side to The All American Boy, was his first), would likely have been ignored without the attention Bobby Bare generated. And yet, when Bare got out of the Army, Presley’s career was flying high again and most people cared little about Bare’s role in that chiding song about The King….

The same trade mags also included a Fraternity spread calling Parsons “a great new star on the horizon” (that’s buried in the fine print on the right photo) and introducing a quick followup song to The All American Boy. But music critics, who saw through it all, later said Educated Rock ‘n’ Roll, which was Bill Parsons’ second vocal release (Rubber Dolly, the B-side to The All American Boy, was his first), would likely have been ignored without the attention Bobby Bare generated. And yet, when Bare got out of the Army, Presley’s career was flying high again and most people cared little about Bare’s role in that chiding song about The King….

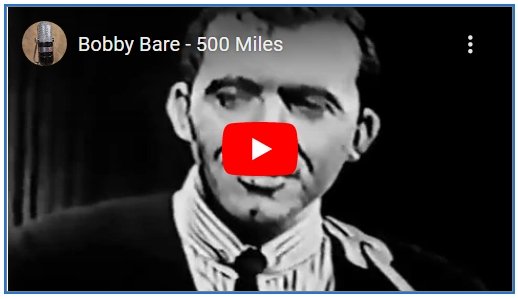

Four years after Parsons’ unc omfortable appearance on American Bandstand, Bare got his turn. But the AB producers were kinder to Bare, still requiring him to lip sync the sung lyrics, but showing cover shots of the teen crowd during the talking bridge portion of Bare’s hit song 500 Miles Away from Home.

omfortable appearance on American Bandstand, Bare got his turn. But the AB producers were kinder to Bare, still requiring him to lip sync the sung lyrics, but showing cover shots of the teen crowd during the talking bridge portion of Bare’s hit song 500 Miles Away from Home.

Here’s Bobby Bare’s AB performance on Nov. 16, 1963 (Run time 2:59)

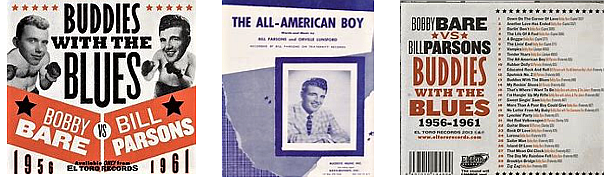

Years later, Bare laughed at the incorrect record labeling affair, saying “I told Bill to take the money and run. I was in the Army, so what would I have done with it? I told him It’s only rock ‘n’ roll and the song would be forgotten in a few months.” But some producers and record companies didn’t forget. For many years after, there were numerous Bill Parsons-Bobby Bare records and CDs — some bootlegged — featuring both original and alternate takes of the singers’ very early recordings—some never before released.

There was little question where Bare got his inspiration for The All American Boy. He was watching Elvis’ career events and thinking about his own career, which in the early and mid ’50s had less than mediocre success. Songwriter Bare knew the song had potential because it was about a blockbuster singer no one could ignore, though Elvis Presley’s name was never mentioned in the lyrics. Certainly, The All American Boy was a novelty song.

Many radio jocks called it controversial. Music critics said people seemed to either love or hate the song along gender lines. On one side was Presley’s hordes of female fans, many of whom cried their eyes out over his induction into the Army.

Conversely, a lot of males felt the song was poetic justice for Elvis’ almost hypnotic spell over all those women. It was a huge tavern jukebox song, and while a lot of radio deejays overplayed the battle of the sexes angle, others aired the song with little comment. It was, after all, a pretty conservative time when most program directors wanted to avoid controversy. And that may explain why several record labels rejected The All American Boy — regardless of whose name was on it.

By the end of 1963, Bare’s country music career moved into high gear with pop chart hits Shame on Me, Detroit City and 500 Miles Away From Home. He became one of the nation’s prolific country singer-songwriters, releasing more than three dozen albums, and scoring eight Hot 100 pop chart single hits (seven of them crossovers from country), and an astounding 69 songs on Billboard’s Top 100 Country charts. He is a Grammy Award winner and a member of both the Grand Ole Opry and the Country Music Hall of Fame. Bill Parsons exited the music business in the early 1960s after none of his several single releases charted.

Some comments may be held for moderation. (New users)