When baby boomers speak of the first “rock ‘n’ roll” radio station in town, usually a station that began playing pop and rock music in the late-1950s to the early-’60s, they are in fact describing the first “Top 40” radio station in town. The birth of actual “rock” radio trailed behind Top 40, arriving in the late-’60s and early-’70s.

When baby boomers speak of the first “rock ‘n’ roll” radio station in town, usually a station that began playing pop and rock music in the late-1950s to the early-’60s, they are in fact describing the first “Top 40” radio station in town. The birth of actual “rock” radio trailed behind Top 40, arriving in the late-’60s and early-’70s.

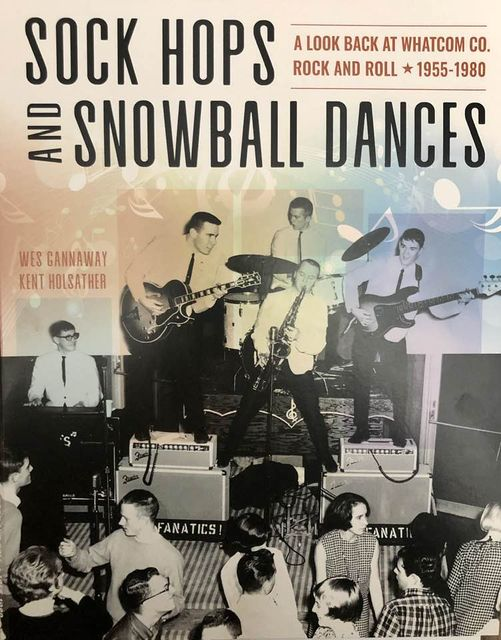

This article began in 2022 when I contributed material for the book Sock Hops and Snowball Dances: A Look Back at Whatcom County Rock and Roll 1955–1980 by Kent Holsather and Wes Gannaway. I realized that the evolution of Top 40 radio in the Pacific Northwest could be brought to life with vintage photos, news clippings, airchecks and video. This is the first of a two part series. Part 1 presents an overview of early radio stations, in northwest Washington and British Columbia, with the focus on the evolution of Top 40 radio. Part 2 describes, step by step, the history of Top 40 coming to the city of Bellingham in the northwest corner of Washington State. …. Steven L. Smith

The 1950s: Broadcasting in Transition

Television surpassed radio as the dominant broadcast medium in the early-1950s. Classic Golden Age of Radio programs – dramas, comedies, soap operas, quiz shows, live music and talent contests moved to television. Radio was losing its biggest stars: Jack Benny, Bing Crosby, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Red Skelton, Gene Autry and many more. Moreover, classic radio shows such as Truth or Consequences, Amateur Hour, Ozzie and Harriet, the Lone Ranger, Superman, Dragnet and Gunsmoke were migrating to TV.

Radio was Fading

In the early-1950s, radio was trying to find a new niche before it vanished into the abyss. The first broadcasters, in the ’20s, had hired local musicians to play live on-air. But that landscape changed dramatically after the national radio networks (NBC, CBS, Mutual and much later ABC) were founded. For a quarter of a century, many network affiliated stations had carried heavy doses of big name network entertainment and national news. With television moving in, suddenly radio stations were forced to experiment with new ideas. They were turning to local news, sports, talk, interviews and hometown deejays spinning popular records. That’s when legendary deejay Alan Freed moved from Cleveland to the Big Apple. Bob Salter and Don Hedman were on the air in Seattle. Red Robinson was a teenage deejay in Vancouver BC. And in Bellingham, Dave Hall and Lee White were deejays at KPUG. Around the country, radio programmers hoped to discover, or stumble on, something fresh and different. One innovation was key to revitalizing radio. That innovation became known as Top 40 radio.

In the early-1950s, radio was trying to find a new niche before it vanished into the abyss. The first broadcasters, in the ’20s, had hired local musicians to play live on-air. But that landscape changed dramatically after the national radio networks (NBC, CBS, Mutual and much later ABC) were founded. For a quarter of a century, many network affiliated stations had carried heavy doses of big name network entertainment and national news. With television moving in, suddenly radio stations were forced to experiment with new ideas. They were turning to local news, sports, talk, interviews and hometown deejays spinning popular records. That’s when legendary deejay Alan Freed moved from Cleveland to the Big Apple. Bob Salter and Don Hedman were on the air in Seattle. Red Robinson was a teenage deejay in Vancouver BC. And in Bellingham, Dave Hall and Lee White were deejays at KPUG. Around the country, radio programmers hoped to discover, or stumble on, something fresh and different. One innovation was key to revitalizing radio. That innovation became known as Top 40 radio.

Birth of the Top 40 Format

In 1951, a young entrepreneur named Todd Storz bought a radio station in Omaha. He sought a new format that would maximize listenership. Storz visited restaurants, nightclubs and bars that had jukeboxes. He discovered that the people feeding coins into the jukeboxes played the same 20 new release pop songs over and over again. That research led to his new radio format — Top 40. The ever changing playlist always consisted of the 20 most popular jukebox songs. To combat redundancy, Storz added 20 more records that were coming on strong or they’d begun to fade. A few recognizable oldies completed that first ever Top 40 playlist. A ratings smash in Omaha, soon radio stations in the U.S. and Canada were cloning the hot new format. That mix of pop (and soon to be early rock ‘n’ roll) blossomed into a cultural phenomenon in the mid-1950s and the ’60s. Although Top 40 began with a radio station in Omaha tracking jukebox hits, soon Billboard, Cashbox and other trade magazines were publishing weekly Hot 100 charts. Radio programmers would tailor those charts to local markets, but the first 40 singles on the Hot 100 could be considered the national Top 40.

What is Top 40?

“Top 40 playlists were never about genre,” according to Gary Shannon, a ’60s jock at KPUG in Bellingham and later the music director at KJR in Seattle. “It was always about putting front and center hit songs from artists of every type. That was Top 40’s DNA. In the early-1950s, a Top 40 playlist consisted almost exclusively of standard pop songs. Then what I call ‘chicken rock’ – bland covers of early rock and rhythm and blues (R&B) – crept onto Top 40 playlists. Pat Boone’s covers of Fats Domino and Little Richard are classic examples. Public acceptance of chicken rock helped grease the way for the modern era of Top 40.

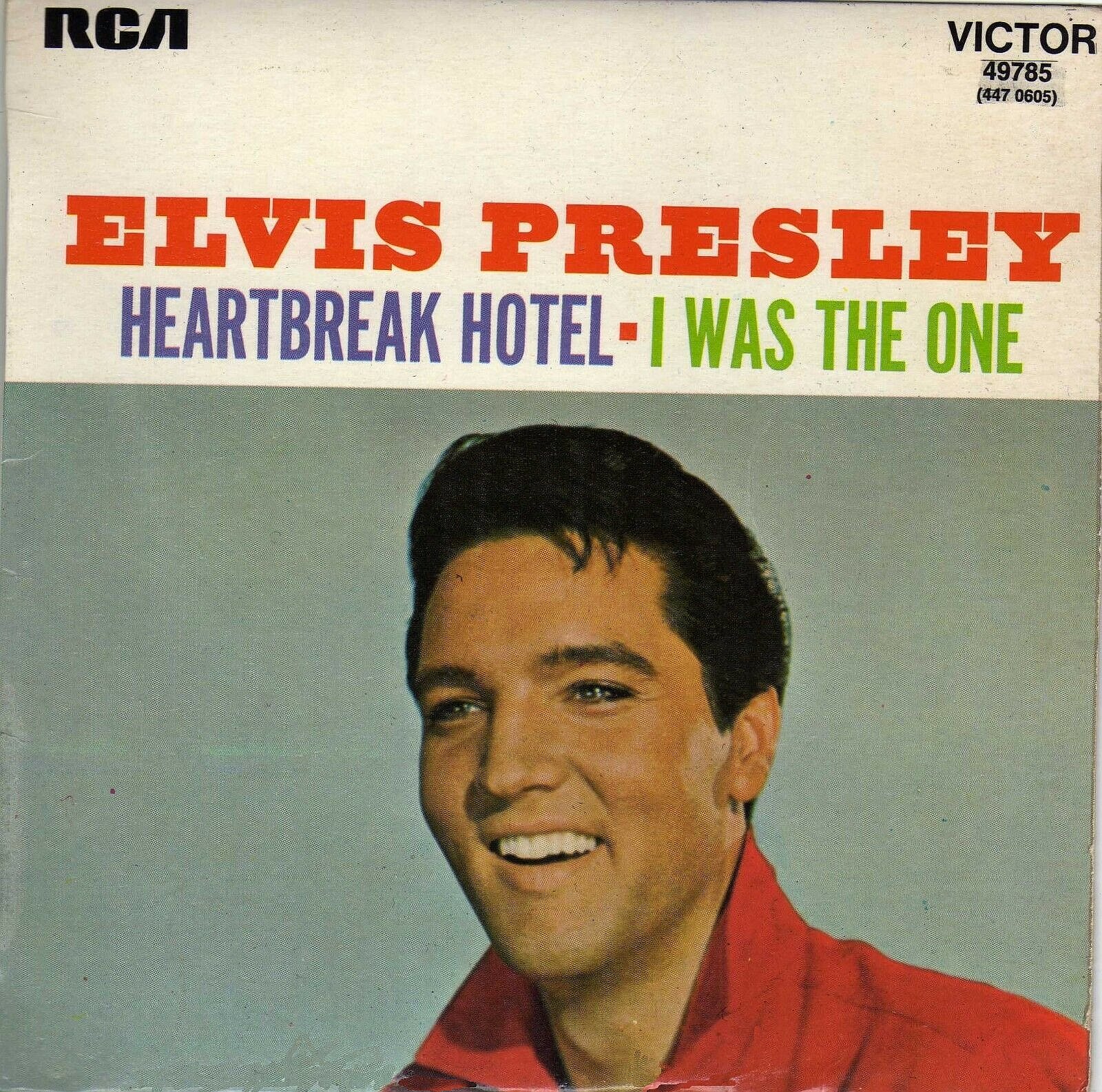

“Top 40 really took off with Elvis’ first No. 1 smash in 1956. “Heartbreak Hotel” opened the door wide for Ricky Nelson and R&B artists like Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Elvis’ breakthrough benefited many other stars of the era: Bobby Darin, Connie Francis, Neil Sedaka, Paul Anka, Johnny Mathis, Leslie Gore, Bobby Vinton, the Drifters and the Platters (their first hit dated back to 1955).

“Top 40 really took off with Elvis’ first No. 1 smash in 1956. “Heartbreak Hotel” opened the door wide for Ricky Nelson and R&B artists like Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Elvis’ breakthrough benefited many other stars of the era: Bobby Darin, Connie Francis, Neil Sedaka, Paul Anka, Johnny Mathis, Leslie Gore, Bobby Vinton, the Drifters and the Platters (their first hit dated back to 1955).

“When I was at KPUG in 1966 it was in every way a Top 40 station,” Shannon continued, “heavy on both pop and rock records, but inclusive of a few folk, country, gospel, patriotic, Chicano and novelty songs. The mid-20th century melding of rock and pop happened on AM radio and we called it ‘Top 40.’ Many of the early Beatles’ songs, especially those written by Paul McCartney, were more pop than rock. A Top 40 station wasn’t the same as a rock ‘n’ roll radio station. The first true ‘rock’ stations, mainly FMs, didn’t appear on the radio dial in the northwest until 1968 when KOL-FM and CKLG-FM transitioned to the format — often referred to as ‘underground’ radio.”

Top 40 Reached for the Stars

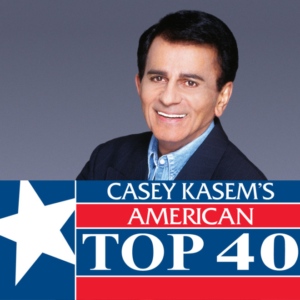

Several nationally syndicated TV and radio shows emerged when Top 40 became a force to be reckoned with. Those mass appeal programs reached an audience of millions — strongly influencing both pop culture and radio station playlists. Conversely, many of the shows that appealed to teens wouldn’t have existed without Top 40 radio. American Top 40, Casey Kasem’s weekly radio show that tracked Billboard’s chart hits, debuted in 1970 and it ran for 18 years. AT-40 was the backdrop to the lives of baby boomers and Gen Xers. Casey wasn’t ‘rockin’ when he counted down the Stones, Cream, Hendrix or Led Zeppelin – he was just playin’ the ever changing Top 40 hits!

Several nationally syndicated TV and radio shows emerged when Top 40 became a force to be reckoned with. Those mass appeal programs reached an audience of millions — strongly influencing both pop culture and radio station playlists. Conversely, many of the shows that appealed to teens wouldn’t have existed without Top 40 radio. American Top 40, Casey Kasem’s weekly radio show that tracked Billboard’s chart hits, debuted in 1970 and it ran for 18 years. AT-40 was the backdrop to the lives of baby boomers and Gen Xers. Casey wasn’t ‘rockin’ when he counted down the Stones, Cream, Hendrix or Led Zeppelin – he was just playin’ the ever changing Top 40 hits!

Speaking of Bubble Gum

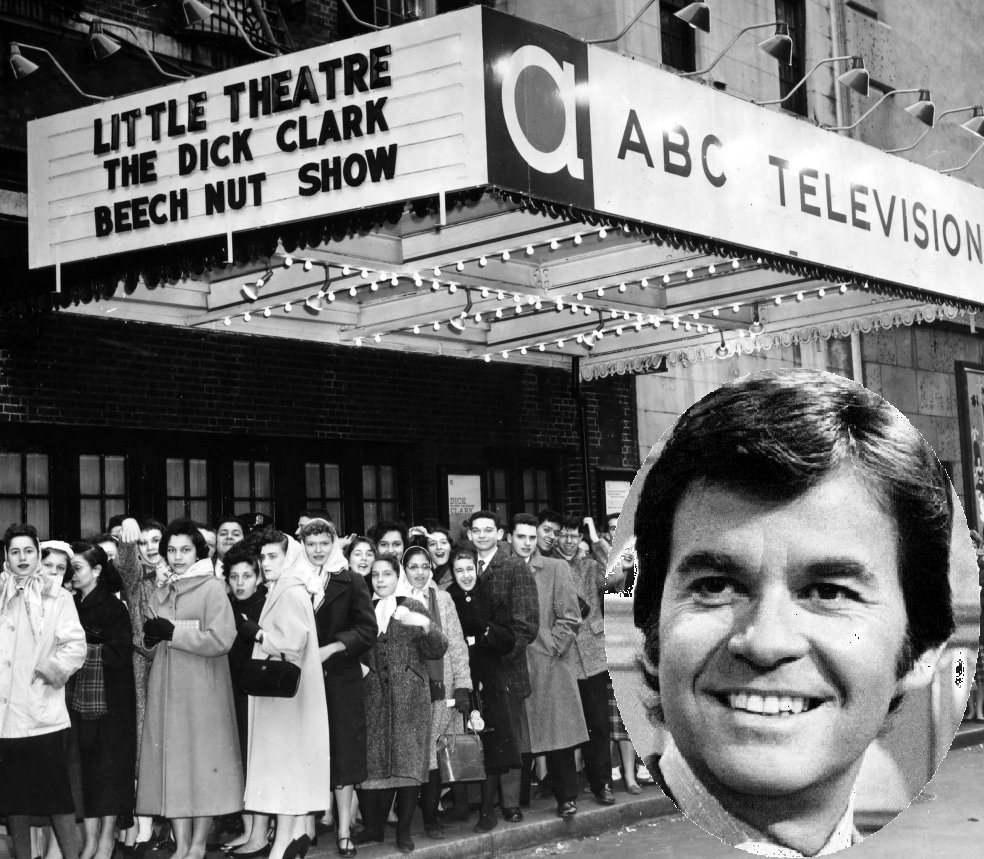

“A dozen years before Casey’s Top 40 countdown,” Gary Shannon explained, “there was Dick Clark’s Beech-Nut Show. It ran Saturday nights, from 1958 to ’60, on ABC TV. The performers were mostly Top 40 hit makers. When cameras zoomed in on the studio audience, everyone was sitting there chewing. Yes! Bubble gum was huge back then and gum wars ensued. Adolescents were often disparagingly referred to as ‘bubble gummers’ or they were described as being into ‘bubble gum’ music. Dick Clark’s iconic American Bandstand was another giant – three thousand TV episodes from 1952 to ’89. And there was Your Hit Parade, sponsored by Lucky Strike, beginning on radio in the 1930s and moving to television (1950 to ’59). Those shows all influenced Top 40 radio in a big way and vice versa.”

Those Fab ’50s

Stereotyped as hyped-up fast talkers, Top 40 disc jockeys had one thing in common – energy – which varied depending on the jock’s personality and the station’s image, jingles, etc. “The best deejays had plenty of energy and the ability to be conversational on the air,” according to Gary ‘Taylor’ Bruno, a former Bellingham DJ and a past program director at KJR in Seattle. “At more music and boss radio stations the jock talk was often limited to reciting call letters, song titles, artist’s names and giving time and temperature checks. At the personality-oriented stations, like KJR, the objective was to provide compelling entertainment. If an on-air personality had the skill to be funny then that was an extra benefit. Most Top 40 disc jockeys loved doing what they were doing and that was playing the hits.”

In the 1950s and deep into the ’60s, before FM started to catch on, Top 40 AM radio stations were highly competitive. Every Top 40 program director (the PD was almost always a guy back then) wanted his station to be the loudest and brightest signal on the dial. The unsung heroes were the broadcast engineers. Old vacuum tube radios, standard in every household through the early-’50s, weren’t easy to haul around. In 1954, manufacturers developed cheap, but often tinny sounding, battery-powered hand-held transistor radios. Kids could take radios to the beach or camping. Also popular were the tinny portable phonographs that opened and closed like suitcases. The 45 RPM records, mostly sold to teens and pre-teens, were recorded at maximum volume with little concern about distortion. Quality control deficiencies made audio processing critical to the success of any Top 40 radio station. With processing, the music sounded better on the radio than it did on a kid’s record player and the disc jockey’s voices sounded bigger than life even on those tiny and tinny transistor radios.

Give ’em that Rock ‘n’ Roll

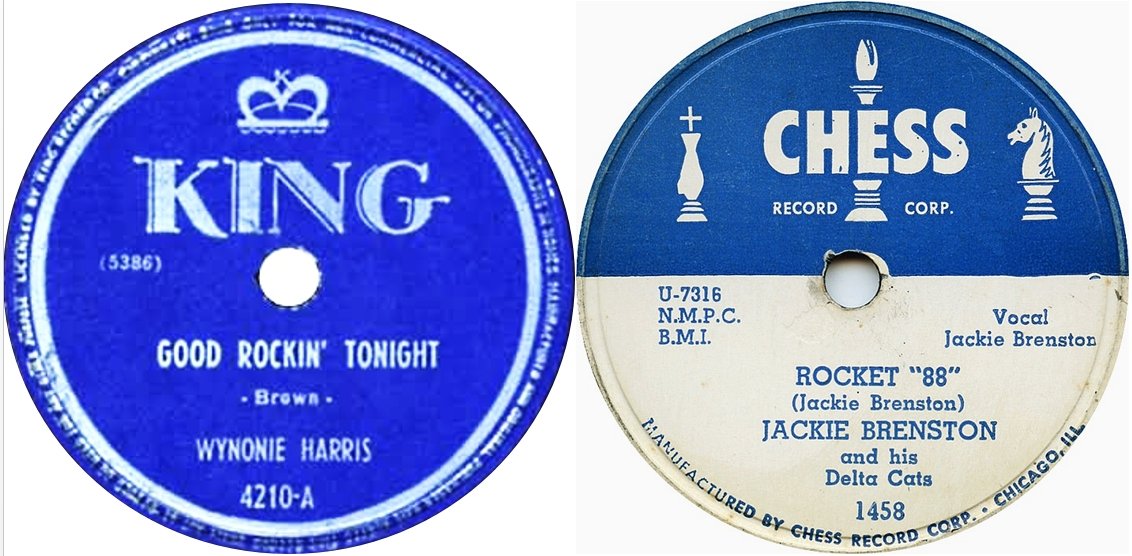

Early rock ‘n’ roll records were a staple of Top 40. Historians debate the identity of the first rock ‘n’ roll record. Two leading candidates are the 1948 jump blues tune “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” by Wynonie Harris, and 1951’s “Rocket 88,” by Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats. (Ike Turner wrote “Rocket 88” and his band backed lead vocalist Brenston, but the record label gave sole artist credit to Brenston.) “Good Rockin’ Tonight” and “Rocket 88” were first distributed as 78 RPM discs, although both records were eventually released as 45s.

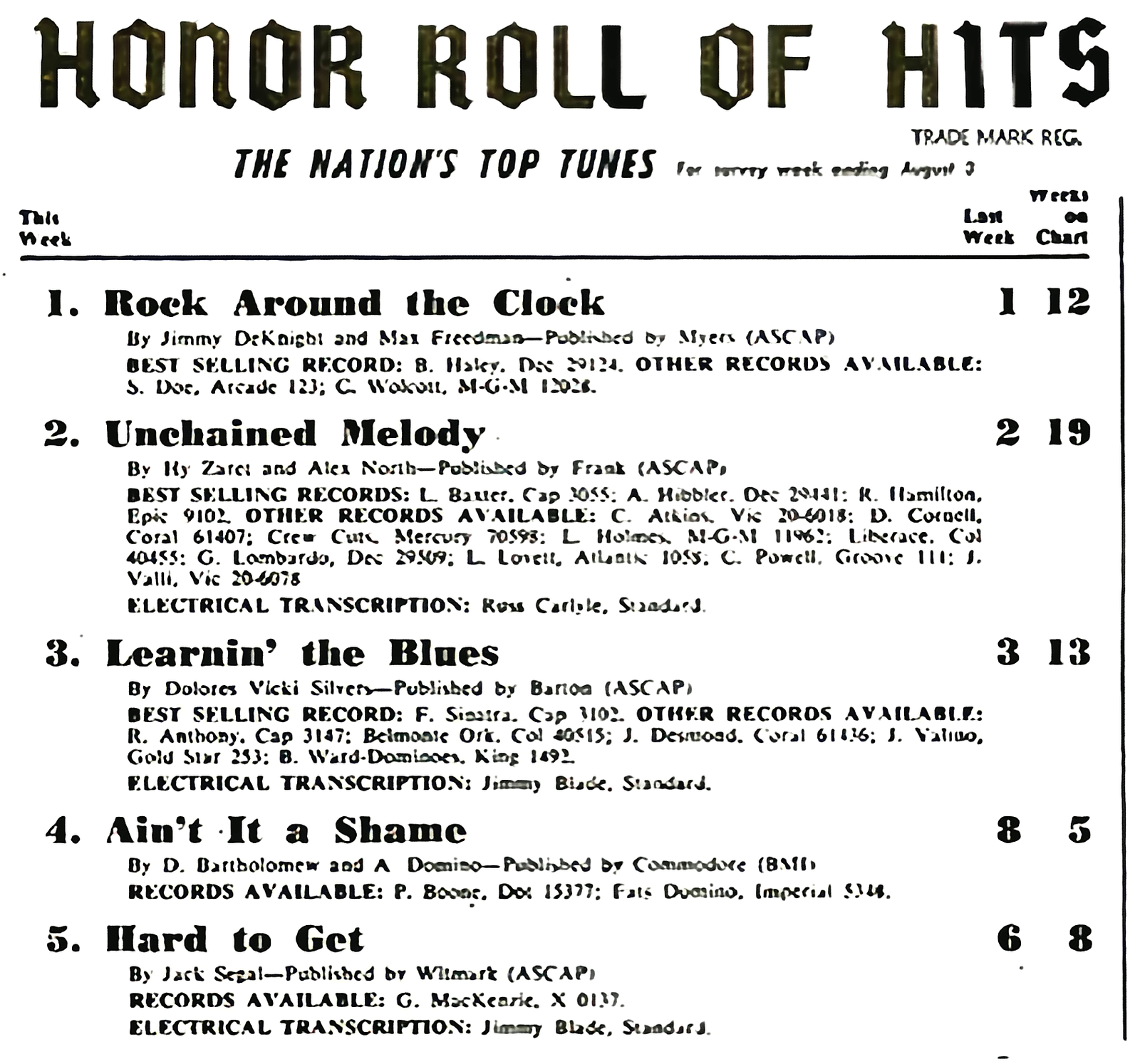

It’s far easier to name the first two rock ‘n’ roll “hits” than it is to pinpoint the first rock ‘n’ roll record. Music historian Joel Whitburn established that Billboard charts ranked “Rock Around The Clock,” by Bill Haley and his Comets, as the No. 1 record for the year 1955. And Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” ranked No. 21 for that same year. Those releases by Bill Haley and Chuck Berry were the first two “hits” of the rock ‘n’ roll era.

Beginnings: Race Music

Cleveland disc jockey Alan Freed played “race music” on his Moon Dog House radio show in 1951. Race music, a blend of blues, jazz and gospel, was created by African Americans for a black audience. Freed, a concert promoter on the side, booked the same artists he played on the radio. Moving to New York City in 1954, Freed continued with his radio show and appeared on teen-oriented TV programs. The ol’ Moon Dog himself made cameo appearances in some of the earliest rock ‘n’ roll themed motion pictures.

Cleveland disc jockey Alan Freed played “race music” on his Moon Dog House radio show in 1951. Race music, a blend of blues, jazz and gospel, was created by African Americans for a black audience. Freed, a concert promoter on the side, booked the same artists he played on the radio. Moving to New York City in 1954, Freed continued with his radio show and appeared on teen-oriented TV programs. The ol’ Moon Dog himself made cameo appearances in some of the earliest rock ‘n’ roll themed motion pictures.

As race music caught on, it got a new name — rhythm and blues. Freed criticized record companies for their vanilla covers of black artist’s music. Despite rumors to the contrary, Freed didn’t coin the phrase “rock ‘n’ roll.” However, his radio show took the expression mainstream. Alan Freed lived high on the hog in his rock ‘n’ roll world, until it all came crashing down: He was the biggest fish caught in the national pay for play payola scandal that rocked the radio and music industries in the early-1960s.

Down Seattle Way

Don Hedman and Bob Salter, the “Salty Dog,” were deejays at KJR in Seattle and innovators in bringing the Top 40 format to Washington State. As early as 1953, preceding the iconic Pat O’Day era at KJR, Salter compiled Seattle’s first Top 40 playlist. KJR went full bore with a Top 40 music format in January 1957. Hedman, at the time, told a newspaper reporter that “during the late morning and early afternoon when I am on the air not many teenagers are listening so the rock ‘n’ roll isn’t played up as much as on other shifts during the day and night. Rock ‘n’ roll is acceptable to many adults, if it isn’t played too much.”

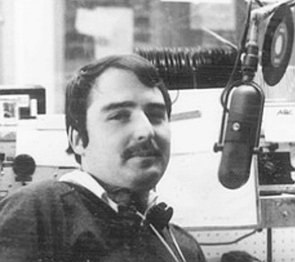

In 1958, Hedman revealed that he “admired and defended” the antics of Elvis, but personally he was “partial to big band music such as Ted Heath and Glenn Miller styles – folk songs, Harry Belafonte and Frank Sinatra.” Not every purveyor of early rock ‘n’ roll was a huge fan of the genre. Hedman relocated to Bellingham in 1962, taking a position with radio automation manufacturer and music programming service International Good Music (IGM). Don eventually left IGM, but he remained in Bellingham and worked into the new millennium as a Whatcom County Realtor. Click HERE to read more about Don Hedman’s broadcasting career.

Airchecks from the era of Salter and Hedman are rarities, but the Hedman family has retained a few of Don’s KJR promos from the late-’50s (coinciding with the popular TV show The Real McCoys). The clips below include Don’s promos mixed with era appropriate KJR jingles. Tagged on, at the end, are two jingles from Don’s years (1959-’62) at Top 40 KAYO in Seattle.

(Four of Don Hedman’s promos (Amos McCoy voice) combined with KJR jingles, followed by two of Hedman’s KAYO jingles. Running time 2:24)

It Was All Red Up North Canada Way

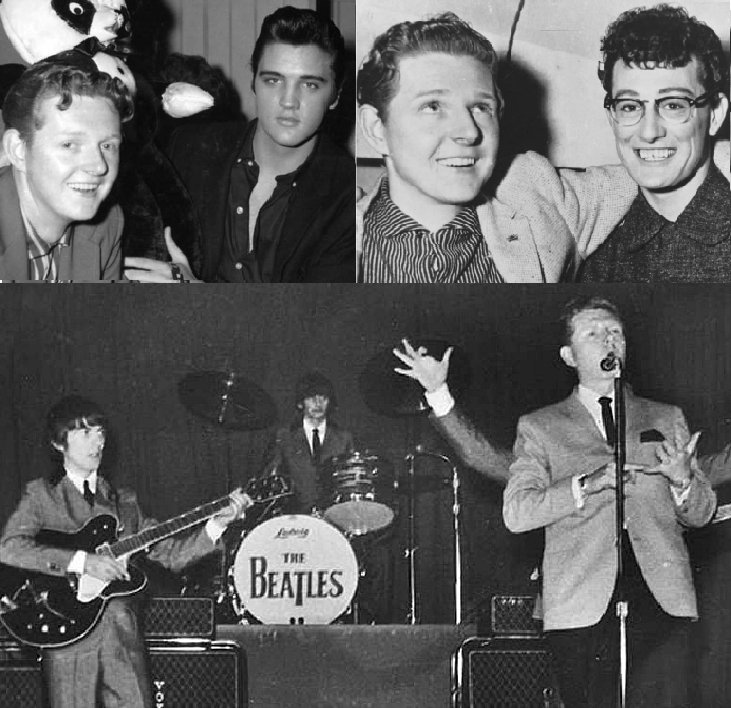

Many a teen in the Pacific Northwest developed an appetite for rock ‘n’ roll music by listening to CJOR in Vancouver, BC. The station’s powerful signal reached into Whatcom County and other parts of the state. In 1954, CJOR gained a fan base in the U.S. when Red Robinson, a high school age disc jockey, first went on the air. His Theme for Teens ran after school weekday afternoons. Red was exciting: He emceed pop and rock concerts and hobnobbed with the stars — Elvis in 1957, after that Buddy Holly, Guy Mitchell, Roy Orbison and in 1964 the Beatles.

Dateline 1958: Organizers of a teen dance in the small border town of Sumas, WA hired Red to cross-over into the U.S. to spin his personal stash of hit records. Red was always a big deal. Even after his retirement in 2017, Red remained one of Canada’s most famous disc jockeys. On Vancouver radio for more than 60 years, he was the host of Red’s Classic Theater — a movie night feature that ran Sundays (1989-2000) on KVOS TV in Bellingham. Click HERE to explore Red’s early years and to hear an aircheck from 1957. To watch a video of Red appearing on KVOS-TV, click HERE.

Dancing the Night Away

In the 1950s, Whatcom County radio stations didn’t play much, if any, rock ‘n’ roll. But teen dances were on the upswing. By 1956, local organizations including the Bellingham YMCA, the Old Settler’s Picnic in Ferndale, the Northwest Youth Council, the Sumas Community Days Festival and private promoters were sponsoring record hops, sock hops (we ain’t got no shoes on!) and dances with live music. Top entertainment spots for teens were the Bloedel Park clubhouse, the Elk’s Lodge and the Eagle’s Hall in Bellingham, the Ferndale and Sumas skating rinks, Ferndale’s Pioneer Park pavilion, Everson City Hall, the Holiday Ballroom near Burlington, Seven Cedars dance pavilion in Mount Vernon, and many school gymnasiums and grange halls. Three popular ’50s bands that played in the northwest corner were the Frantics (Werewolf), the Continentals (Cool Penguin) both out of Seattle, and the Swags (Rockin’ Matilda) from Whatcom County. By the mid-1960s, several new dance venues debuted: the Assumption Gym in Bellingham, Village West, the Forest Grove Ballroom and the Beacon Ballroom all in Birch Bay-Blaine.

Big Name Acts

Buddy Knox played at the Assumption Gym as the highlight of the 1963 Blossom Time Festival. KPUG announcers Gary Bruno, Danny Holiday and Dick Stark teamed up to bring Knox to town. Knox’s single “Party Doll” had been a No. 1 hit in 1957. Another nationally recognized rockabilly artist, Robin Luke, played at the Holiday Ballroom in 1958. His song “Susie Darling” was inspired by, and named after, his 5-year-old sister.

Whatcom County Radio Stations in the ’50s

In spring 1958, three AM radio stations were on the air in Bellingham: KVOS, KPUG and KENY. (In 1961, the KVOS call letters changed to KGMI and in 1968 KENY became KBFW.) In north Whatcom County, the town of Blaine had KARI AM: The religious format, aimed at British Columbia, drew very few American listeners. To the south, KBRC AM in Mount Vernon didn’t impact listenership in Whatcom County. But, for many years, KBRC serenaded adults in the Skagit Valley with easy listening pop music, except in the nighttime hours they played more rock ‘n’ roll for teenagers. FM radio didn’t gain much traction with listeners in Whatcom County until the mid-’80s.

KVOS AM Radio (later KGMI)

KVOS radio didn’t have much to do with the evolution of Top 40 radio in the northwest. However, KVOS was one of the first radio stations in the state, and it’s the only Bellingham radio station with roots going back to the early days of radio’s Golden Age. Therefore, KVOS’ story will be told here in part 1 of this series.

In December 1926, KVOS went on the air as the eleventh radio station in Seattle. Original licensee, Louis Kessler, was the president, general manager, program director and, for much of the time, the only staff announcer. Kessler’s talents lay in entertainment: public speaking, comedy and music. His father, a Seattle clothier, as well as another Seattle (formerly from Bellingham) businessman, held financial stakes in KVOS.

Fledgling station KVOS broadcast with 50-watts — not much power, but not uncommon at the time. About two years later, the Federal Radio Commission (precursor to the FCC) authorized upping the power to 100-watts. After multiple incremental power increases over three decades, in 1960 KVOS began operating at its present 5000-watts daytime power.

Voice of Seattle

The “K” at the front of the KVOS call sign was assigned by the government. Kessler had input into the remaining letters and he promoted “KVOS” as standing for “Kessler’s Voice of Seattle.” For awhle, KVOS’ studio and transmitter were located at the 13 story New Washington Hotel on Second Avenue and Stewart Street downtown. Actually, that was the station’s second and last Seattle location. For the first four months of its life, KVOS was housed on the roof of the Rosita Villa apartments on Queen Ann Hill.

Escalating Debt

Revenue was elusive. Radio was still experimental, an amusing curiosity. Newspapers generated much of their income from paid subscribers. Radio’s best hope for survival, at least by lawful means, required selling advertising or bartering airtime for goods and services. Unfortunately for broadcasters, merchants didn’t look upon radio as a necessary part of any advertising budget. Therefore, operating costs at a radio station had to be kept lower than low.

Kessler didn’t land sponsors often enough to stave off chronic money problems. Seattle’s larger operations such as KOMO and KJR could afford to compensate local musicians for live performances. Lou, running his part-time radio station that was initiall6 on the air mainly at night, usually spent his evenings spinning low fidelity 1920’s era 78 rpm phonograph records. Sometimes he’d select records to fit with a theme – all dance tunes, all big bands, or maybe kid’s songs. As KVOS’ operating hours expanded gradually, a new daily morning show, the “Housecleaning Hour of Music,” was themed to offer “peppy jazz” for housewives who were dedicated to vacuuming their homes.

North to Bellingham

When KVOS was operating in Seattle, Kessler occasionally ran live in-studio musical performances. But he didn’t have a Seattle-sized budget that could compete with the large stations. In less than one year, upon his request, the radio commission granted Kessler approval to move his radio station 90 miles north to the small city of Bellingham, WA. The call letters remained the same, but the “Voice of Seattle” moniker was dropped. In Bellingham, KVOS was known as the “Mount Baker Radio Station,” an allusion to a nearby mountain peak/ski area.

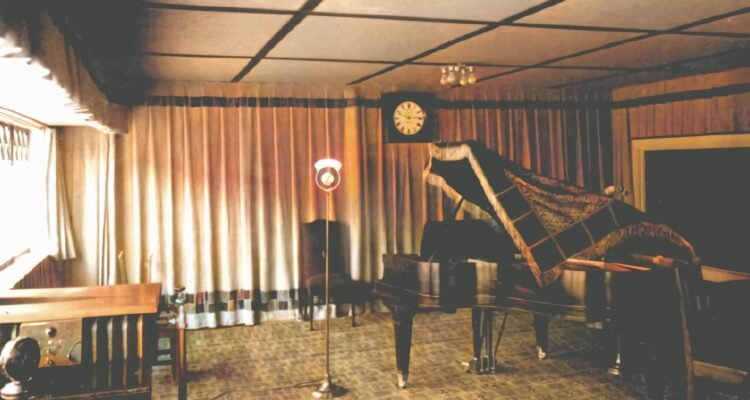

Live from Bellingham

In the latter years of the Roaring Twenties, the Mount Baker Radio Station’s first broadcast originated from a new studio in Bellingham’s historic Hotel Henry (the Bellingham YMCA since 1944). It was far easier to move a radio studio and a transmitter back then when the transmitting antenna was a long horizontal wire on the roof of a building versus a tall stationary steel tower with a complex grounding system. That first extravaganza from Bellingham took place on Halloween Eve 1927. Live music and the proverbial speeches by local politicians and dignitaries prevailed. In the short time he was in Bellingham, Louis Kessler made an indelible impression. Thirty years later, he was remembered by the business community as that “cigar toting sharp-dresser who had owned the wireless station.”

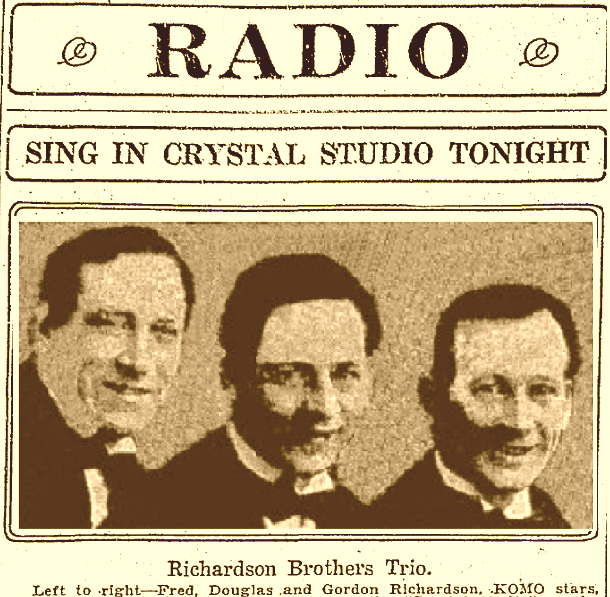

Kessler hoped to mostly retire his phonograph records when he got to Bellingham. Five days before the Halloween broadcast, he signed a talent agreement with Douglas Richardson and, shortly after, with Richardson’s two brothers. Douglas, Fred and Gordon Richardson were tenors and, together or individually, they performed on radio stations in Seattle and Los Angeles. Kessler’s deal with the Richardsons put Bellingham on that list of cities. Doug Richardson became a national star, later appearing on the NBC Radio Network and signing a recording contract with Columbia Records.

Beginning in fall 1927, the Oofty Goof Show became a hit in Whatcom County. A corny Scandinavian themed musical comedy, its roots went back to Kessler’s days in Seattle. Lou re-cast the program with Bellingham talent. The main “extemporaneous fun makers,” according to the Bellingham Herald, were Fairhaven High School student Marion Bodiker (Oofty) and Whatcom High School student Ione Roll (Goofty). The girls sang silly ditties and played (respectively) banjo and ukulele. Einar Moen, a pianist and later a Bellingham music instructor and well-known organist, directed the Oofty Goofs Orchestra and shared his wit and warm personality.

More than two dozen local musicians performed on Kessler’s KVOS when it was in Bellingham. If Lou wasn’t presenting live music, the programming fell back on staples of the era: farm reports, religion, politics, interviews, poetry, education, sports, a few records and brief news reports.

Financial Reckoning

Prohibition was the law of the land, and the country teetered toward the Great Depression, when the owner of a Bellingham radio shop asked a judge to force KVOS into receivership. Kessler had failed to pay a $175 overdue invoice. Immediately after, in January 1929, the Bellingham Herald reported on Kessler’s financial problems and many more creditors came forward: Debts exceeded the assets by five-fold. A judge ruled that Kessler was out, no longer the station manager. A local businessman was appointed as the receiver and KVOS was to be auctioned off. (Kessler lost his radio station, but after moving back to King County he worked in sales, law enforcement and filled important positions with county and state governments.)

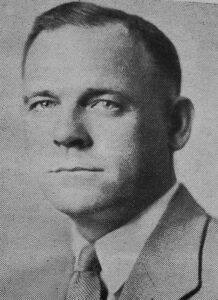

Along Came Jones

The court ordered forced sale of KVOS took place on April 15, 1929. The high bidder was a banker, a print shop owner and the head of the Bellingham Chamber of Commerce. He acquired the ailing radio station for $8,500. Within a week, at a price of $9,000, he sold KVOS to a company headed by Lafayette “Rogan” Jones. (Rogan was the principal buyer and his minority partner was Harry Spence, a veteran of Tacoma radio.) Jones was of Irish heritage, born in Tennessee, and as a youth he’d moved to Aberdeen, WA with his family. He had been a banker and a commercial landlord with no interest in radio. Then radio station KXRO that leased space in one of his buildings went dark. To recover the losses, in summer 1928, Rogan and his brother Goodbar Jones reluctantly took control of the defunct Aberdeen radio station. Rogan soon realized that the radio business showed promise. He and Spence, who’d been raised in Bellingham and was the manager of the Aberdeen station, purchased KVOS in spring 1929. By October 1929, Jones’ firm had ownership interests in a total of four radio stations: Seattle, Wenatchee and, of course, Aberdeen and Bellingham. Initially, Spence commuted and managed both the Aberdeen and Bellingham stations. Then Spence’s brother-in-law, Fred Goddard, took over in Bellingham. In spring 1931, Rogan moved north to personally manage KVOS. Years later, Jones stated that by purchasing four radio stations in such a short period of time he’d depleted his finances and that led to hard times as the Great Depression deepened.

Bringing Back the Music

The live in-studio musicians had started to fade away when Lou Kessler was running out of money in 1929. Gradually, Jones brought back a few of the live musicians. One triumph was locally grown and nationally renowned violinist Catherine Wade-Smith. A child prodigy, playing her first concert at age 7, she performed across North America. Wade-Smith’s classical violin concerts turned to wedding bells in 1931 when she wed Rogan Jones. Her touring years over, Catherine became active in local civic organizations and charities. She settled in as a valuable partner in Rogan’s many business enterprises and they raised a family. Rogan and Catherine were together until he passed away in 1972.

Jones didn’t retain dozens of musicians on his staff, as had his predecessor. However, Rogan maintained ties with a number of popular local performers: pianist Anna Spees, baritone Ralph Hennes (the Carolina Street Canary), Gordon Smith (singer, guitar and ukulele) and Einar Moen (the keyboardist who’d been with the Oofty Goofs Show). As the 1930s ebbed and the 1940s commenced, few musicians remained at KVOS other than Moen. He was with KVOS for 21 years, until 1948, although other live performers were mostly gone by 1946 as KVOS became affiliated with the ABC Radio Network and its full gamut of variety entertainment and news.

Politically Jones

Jones, a liberal democrat, focused less on music and more on airing politics and opinions that would shake-up the county’s then conservative leaders. Controversy attracted an audience. But to keep emotions from boiling over, KVOS mixed in low-key programs: cooking shows, farm news, sermons, kid’s spelling bees, do-it-yourself advice, and educational, medical, fitness, and financial information. In the late-1920s and the early-’30s, KVOS hosted some pretty unusual characters.

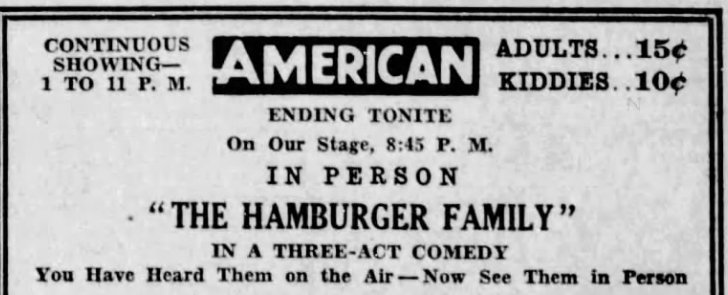

Hamburger, Bridge, Quackery, Teeth and the Occult

The Hamburger Family was a locally written and produced soap opera. The cast, including Rogan Jones’ mother-in-law, occasionally made guest appearances between movies at Bellingham’s American Theater. The Bridge Game by Radio satiated the cravings of card sharks looking for trump cards. Dr. Delbert Darst, a chiropractor and a holdover advertiser from Lou Kessler, was a “drugless physician” able to cure maladies, ranging from high blood pressure and cancer to male and female sexual disorders, with concoctions of sauerkraut juice, salt elixir and induced electric currents derived from fluctuating magnetic fields. Healthy teeth were assured by following the sage advice offered on the weekly Dental Clinic of the Air. Madame Clotho R. Hansone (real name Katherine Ellis) shared her prognostications after gazing into her crystal ball and offering expert analysis of spent tea leaves. A fortune teller and a Bellingham resident for most of her life, Hansone appeared internationally as the vaudevillian psychic and spirit medium often billed as the “Feminine Mental Wizard.”

Young Bill Mock

The first KVOS staff announcer, not counting the owner of the station or a musician standing in as an announcer, was Bill Mock. Graduating from Whatcom High School in 1925, he’d excelled at speech, writing and theater (a founder of the Bellingham Theater Guild in 1929). For a few years, Bill worked retail in downtown Bellingham. His first broadcasts on KVOS (sports reports) came about in 1931. Leaving the station after a year, Mock headed to the Palouse to attend Washington State College (now Washington State University). Earning his degree with honors, Bill returned to KVOS for two years (1936-’37), then he accepted a job as news director at KEX in Portland. By the late-1950s, Mock was a sportscaster at KIRO radio in Seattle and, come the early-’60s, he’d moved to KVI. Mock quit radio in the mid-60s, taking a sales position at an athletic supply company in Seattle.

No News was Bad News

The state of broadcast news in the 1930s frustrated Rogan Jones. The Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI) wire services, kowtowing to newspaper publishers, discontinued news services for radio broadcasters. A one-sided Press-Radio Agreement was offered — a compromise where radio was limited to two 5-minute newscasts per day and the morning news couldn’t air before 9:30 and the evening report had to be delayed until 9:00 at night. Going on, it said all news stories were limited to 30 words or less. Jones was having none of that. He refused to sign the compromise deal. His next move turned the newspaper industry upside down.

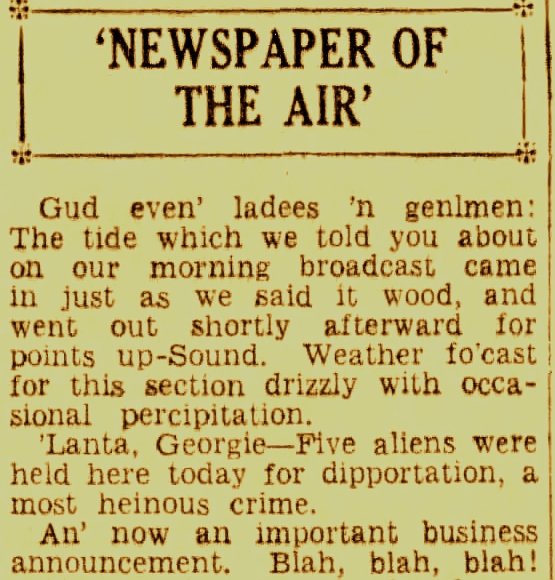

Newspaper of the Air

The Newspaper of the Air began small in 1933, but it grew into five daily 30-minute newscasts, commentaries and editorials. The newscasts unabashedly came from the pages of the Bellingham Herald, the Seattle Times and the Seattle PI. Sometimes announcer Bill Mock, or two reporters (who were charged with procuring early editions of the newspapers) read the news on the air. But the firestorm that caught national attention was largely because of L.H. Darwin — the man Rogan Jones chose as the commentator and sometimes newscaster.

Leslie H. Darwin was an infamous and cantankerous local character. Born in Decatur, AL, he’d moved to New Whatcom in the 1890s (the town was consolidated into Bellingham in 1903). Darwin’s first traceable job, in 1894 at age 19, was with the Seattle PI’s circulation department in Whatcom County. Four decades, and many jobs later, he joined KVOS’ Newspaper of the Air. Darwin had a unique sound. A Bellingham businessman, who listened to Darwin, said: “His dribble puss tone sounded like slush coming off a corrugated roof. All the while, you could hear him rustling the pages of the newspaper he was reading from at the time. He said he sympathized with poor ‘widders ‘n’ orphums,’ meaning widows and orphans.” Darwin’s strange dialect was often lampooned by the Bellingham Herald in unflattering articles and cartoons.

The Ramblings of L.H. Darwin

Les Darwin’s life, before the Newspaper of the Air, is easy enough to track in old news clippings. Darwin got his start with the newspaper business at the confluence of the 19th and 20th centuries. At first he worked for other publishers, but in the mid-1920s he owned his own newspaper in Bellingham. His political positions made him a force in the liberal faction of the local Democratic Party. Awarded a political plum when his party won the gubernatorial race, Les was appointed to the dual positions of Washington State Fish Commissioner and the state’s Chief Game Warden. When he joined KVOS, a dozen years after he’d left his position with the state, Darwin was pushing 60 years of age and employed as a court appointed estate tax appraiser. Leslie it seems had some heavy baggage: Arrested for blackmailing advertisers at newspapers he’d managed; failure to pay employees back wages; convicted of criminal libel (later overturned); and accused of playing favorites and arbitrary enforcement of state fish and game laws. The left-leaning views Darwin espoused over KVOS riled-up Frank Sefrit, the conservative managing editor of the Bellingham Herald. Sefrit had once canned Darwin and from then on they became arch enemies. The Herald called Darwin the “radio howler,” and Rogan Jones was nicknamed the “radio pirate.”

During the Newspaper-Radio War that followed, Sefrit reviled Darwin as a “madman,” a “Marxist,” and a “blackmailer.” Darwin responded in kind, comparing Sefrit to Nero the cruel Roman emperor. Darwin had many public tiffs with politicians and powerful adversaries; for example, he took on local dairy farmers and administrators at Western (now Western Washington University). The media chaos helped KVOS attract more listeners and it sold newspapers for the Herald. Darwin was fearless, if not always discerning. He deployed Rogan Jones’ radio station to push for the ouster of a county commissioner. That commissioner happened to be the father of Jones’ wife Catherine. As divisive as Darwin was, during those depression years, 40% of KVOS’ ad revenue came from sponsorship of his rants. Jones had little choice but to fire Darwin when in 1937 the two U.S. Senators from Washington State (both democrats) warned that the then Federal Communications Commission would deny the renewal of KVOS’ broadcast license unless Darwin was silenced. The Newspaper of the Air was only a memory by the early 1940s, replaced by shorter newscasts that reported current events without the obvious political slant. Alan Miller, a familiar morning voice during the WWII years, was one of the first of that new breed of KVOS newscasters.

The Supreme Court Rules

In 1936, the Newspaper of the Air led Rogan Jones into the hallowed halls of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Associated Press, egged on by the Bellingham Herald, sued KVOS for “hijacking” AP copy. Initially, the court ruled in favor of KVOS. On appeal, the decision was reversed. At the Supreme Court, the justices determined that the original ruling, in favor of KVOS, could stand. Summarized, the ruling said that once a story appeared in a newspaper, it entered the public domain and it was fair game for other media. That decision changed how broadcasters reported the news, and shortly after, the AP and UPI began offering unrestricted news services to radio stations.

The Man Called Red Ryder

After the rift with the Associated Press, Jones didn’t care to do business with the company that had sued him and the AP wasn’t keen on Jones. He chose to subscribe to the UPI wire service. A story of historical interest transpired in the early years of KVOS’ relationship with UPI. In December 1941, announcer and PD Brooke Temple was at the KVOS microphone as Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor. Alone in the studio, with the teletype’s alarm bells ringing and the noisy printer clanking away in the other room, Temple went live with the incoming news flashes as he scrambled back and forth between the control room and the teletype. That continued until Rogan Jones arrived at the studio to help out. As the war raged on, Brook Temple moved to California where he was an announcer at KSFO in San Francisco and at KHJ in Los Angeles. Both stations were owned by the Don Lee-Mutual Network, an American radio network with affiliates across the nation. Temple had a manly voice that attracted attention at the network. In 1946, he was cast as the star of the old radio show Red Ryder. Millions of kids from coast to coast listened to the famous fighting cowboy. It’s little known, but interesting, that one of KVOS’ early announcers became a cowboy star during the Golden Age of Radio. (QZVX has obtained a recording of Brooke Temple’s historic Pearl Harbor broadcast on KVOS and it will be included in a future article.)

Surviving the Great Depression

KVOS survived the Great Depression, a testament to Jones’ business acumen and a fair bit of penny pinching. The radio commission didn’t help much either, the agency kept changing KVOS’ frequency (dial position) and that wasn’t conducive to long-term stability. Those were desperate times: Fred Goddard, Rogan’s longtime business associate, recalled the day the studio and transmitter were moved from the Hotel Henry to another downtown hotel: “A transfer company was hoisting the transmitter up the side of the building and over the roof [an 8-story building]. If the rope should break, KVOS would have no transmitter and KVOS would not go on the air. I asked Rogan if he had insurance to cover the transmitter. I always remembered his remarks, dictated of course by the depression. Said Rogan, ‘No, I haven’t and I am going to stand right under it. If it falls all of my worries will be over.’ And believe me he did just that. He stood under the transmitter until it was successfully over the top of the firewall.”

Golden Age of Radio

In 1946, KVOS became the northernmost affiliate of the ABC Radio Network. That gave KVOS access to network news and many of the classic Golden Age of Radio shows: Bing Crosby, George Burns & Gracie Allen, Don McNeill’s Breakfast Club, Walter Winchell’s Jergen’s Journal, and for the kids, the Lone Ranger, Tarzan, Hopalong Cassidy, Dick Tracy, and Lassie.

News, Information & Community

Hourly newscasts and special reports from ABC helped KVOS develop a reputation as the news and information leader in Whatcom County. Paul Harvey’s broadcasts from ABC ran first on KVOS and later on KGMI. Accompanying the news and information, KVOS played easy listening music (hosted by live deejays through 1958). The staff appeared at civic events, grand openings, club meetings and school assemblies. From the 1940s into the early-1960s, KVOS sponsored barn dances, big band and jazz dances for adults in Whatcom and Skagit counties.

The Haines Fay Era

Baby boomers of the Top 40 generation will remember Haines Fay. A standout basketball player at Bellingham High, and then at Western. Fay was only 19 when he began at KVOS in 1946. Fay’s sportscasts were part Whatcom County’s sports lore for two generations of high school students. Haines was equally prominent as a newsman and a talk show host. He was elected to the Bellingham City Council in 1976. Then, in the early-‘80s, he campaigned for the position of mayor of Bellingham. In a gentlemanly contest, Haines was defeated by fellow city council member Tim Douglas.

The audio tracks below feature the familiar voice of Haines Fay. First, when he was running for mayor, Haines described his vision for Bellingham’s future. In the second track, Haines was 18 years retired when he spoke of his long career with KVOS-KGMI.

(Track 1: Haines and Rachel Grossman on KBFW, 1983. Track 2: Haines and Deb Slater on KVOS TV, 2010. Running time 1:55)

For the Ladies

Elaine Wise, probably better-known as Elaine Horn, was the county’s first female radio personality. On KVOS, beginning in the late-‘40s, she hosted Wahl’s Social Letter, Woman’s World,” and Here’s Elaine.” Leaving the radio side of KVOS, she moved to KVOS television shortly after it went on the air in 1953. In 1957, she moved over to KPUG radio. Within a year, she was back at Channel 12. Her daytime TV show Woman’s World, the title appropriated from her radio days, ran for 20 years. All of Elaine’s radio and TV programs were carefully crafted to appeal to an important demographic – mid-20th century housewives.

International Good Music

Rogan Jones was a pioneer of radio automation systems and recorded programming: taped music and canned announcer’s voices all controlled by crude electro/mechanical brains. KVOS automated in 1959, making it one of the first radio stations in the country to do so. That wasn’t a big surprise since Jones owned International Good Music, a manufacturer of automation systems and taped programming. Jones had founded IGM with the vision of providing symphonic classical music and Broadway show tunes to a group of west coast FM stations (including his own KGMI-FM). Soon his vision changed and IGM was producing several popular radio formats. In the early-’60s and ’70s, the easy listening tunes heard on KVOS (KGMI) arrived at the radio station on reel to reel tapes supplied by IGM. The deejay’s voices were the pre-recorded sounds of Don McMaster, Del Olney and Jim French.

KVOS Top 40 NOT!

Rogan Jones said that his musical tastes favored Bach, Brahms and Beethoven. He was dead set against the pop, early rock and Top 40 songs that were emerging in the 1950s. Alarmed by what he heard, in a staff memo, Jones prohibited KVOS employees from playing “modern pop.” He described it in the memo as “neurotic, instrumentalized hysteria, a type of musical epilepsy.”

Rogan Jones retired in 1961 and Jim Hamstreet (formerly with KPUG management and a veteran of Seattle radio), took over as KGMI’s manager. Yet, as the owner and the president of the company, Jones’ didn’t relinquish full control until fall 1969 when he stepped down due to ongoing health considerations. At that point, Hamstreet was appointed president/general manager of KGMI Inc. Given Rogan Jones’ continued ownership of the station, and his distaste for “instrumentalized hysteria,” it’s not a surprise that when Top 40 radio came to Whatcom County in the early-’60s, weekday mornings KGMI was still running the NBC Network’s Golden Age radio show Don McNeill’s Breakfast Club.

KPUG-AM Radio

KPUG went on the air in 1948. Promoted initially as female operated, the majority owner was Jessica Longston. Of the three co-owners, the most actively involved was C.V. “Vicki” Zaser, KPUG’s first local manager. The two remaining co-owners were Mrs. Berenice Brownlow (who held other business interests with Longston) and Mr. Edward Jansen (a Tacoma broadcaster).

Longston and Zaser went back a few years. They’d served together in the Women’s Army Corps during WWII. Zaser had been Longston’s commanding officer. After the war, their roles flipped with Longston taking the lead in matters of business. Together they pursued mutual business interests and formed a tight personal bond. Jessica Longston got her start in the media as a newspaper reporter. Later, she purchased a few small-town newspapers. Then Longston Enterprises began investing in radio stations.

More than forty years ago, Washington State University interviewed Jessica Longston. She described the early days of KPUG and all the obstacles she had to overcome to finally get the station on the air for the first time.

(Jessica Longston interview, recorded in the late-70s (credit to Professor Hugh Rundell, WSU NW Radio Hall of Fame Collection. Running time 5:02)

Robert Pollock

The most consequential KPUG employee ever was Robert Pollock. A newspaperman who worked for Longston, in 1949 he tried his hand at selling radio ads for KPUG. That same year, Vicki Zaser moved back to the company’s Seattle office. Bob Pollock stepped in to become the manager of KPUG. In 1952, he was transferred to Seattle to oversee the operations of all of Longston’s radio stations and newspapers. Jim Hamstreet (later at KGMI) was then appointed manager. After four years, he was chosen by Longston to run KAYO in Seattle. The next manager, taking over in ’56, was John DiMeo. As part of a familiar pattern, DiMeo left KPUG for Longston’s Seattle office. Jim Tincker took DiMeo’s place in 1960. He was the GM until 1976 when Bob Pollock returned to Bellingham to personally manage KPUG. Pollock had purchased KPUG from Longston in 1964, but instead of moving back to Bellingham, he had stayed with Longston for several more years and let Tincker run KPUG (and the FM sister station the company had acquired in 1972).

Early KPUG

Paul Herbold, a decorated navy bomber pilot in the Pacific during WWII, was one of KPUG’s first announcers. The golden-voiced Herbold began in 1948, but he didn’t stay long. Returning to school, he earned his PhD and spent the remainder of his professional career as a speech and communications professor at Western. (In the early-’70s this author spent many entertaining and worthwhile hours in Herbold’s classes.)

Another contemporary of Paul Herbold was “Dynamite” Jackson. In the late-’40s, KPUG was trying to build an audience by appealing to all musical tastes. The station ran “block” programming — individual musical segments that featured exclusively classical, popular, western or Scandinavian tunes. Perhaps the most popular show of the time was Cowboy Capers (every Monday through Saturday) with host Ken “Dynamite” Jackson. “Dynamite” played country-western music and, appropriately so, incorporated farm news into his very popular early morning radio show.

Live in-study recitals by Bellingham organist Gunnar Anderson were a remnant of radio’s Golden Age. Debuting in 1948, for three decades, Anderson’s music remained part of KPUG’s regular Sunday morning programming. In later years, Gunnar recorded his show at a home studio and delivered ready to air reel to reel tapes to KPUG.

National Programming

The Mutual Broadcasting System, a national radio network, provided much of KPUG’s early programming — hourly newscasts, commentators Gabriel Heatter & Fulton Lewis Jr. and the break your heart sob stories heard on Queen for a Day. From the late -1940s into the early-’60s, KPUG played easy listening pop records. And the announcers presented news, farm reports, and sports. Weekdays KPUG ran “ringo,” which was another way of saying radio bingo.

Local Personalities

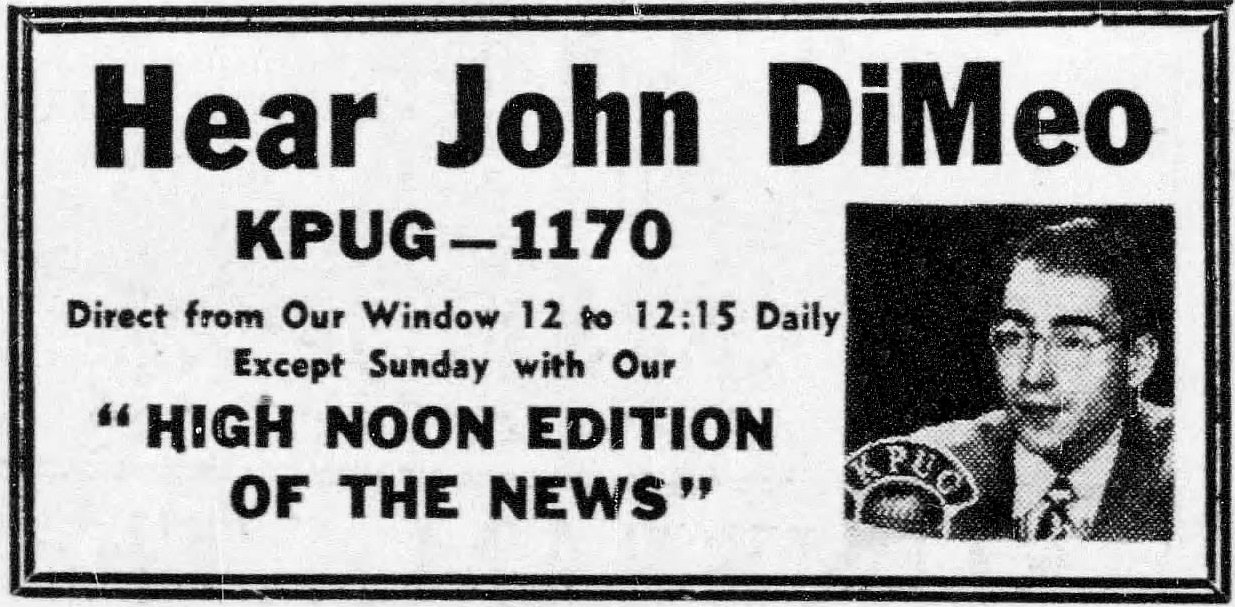

Sports has always been a big part of KPUG’s public persona. Some of the early sportscasters (before Dick Stark arrived in the early-’60s) were Norrie Adams, Bob Dorr (a high school coach in Bellingham), Mal Alberts and Bill Anderson (also news director). Seattle sportscaster Ted Bell was sometimes heard on KPUG. Other voices belonged to newscasters John DiMeo, Phil Ross and Ed Triplett and announcers John Munroe, Tad Jones, Lee White, Bob Concie, Dave Hall, Don Pinney and Bill Berry (future owner of KAGT radio in Anacortes). Ken Jackson (referenced previously) handled farm news for many years and Elaine Horn entertained the ladies.

Just the News

John DiMeo was a standout KPUG employee. He began as a combo news director/sportscaster in 1949. By 1955, he was selling airtime and a year after that he was the GM. DiMeo was elected to the Bellingham City Council and, for a few months in 1957, he was the acting Mayor of Bellingham. In 1960, after transferring to Longston’s Seattle office, DiMeo as a sideline began purchasing radio stations. The DiMeo family still owns several stations in the Pacific Northwest.

The Big Three at KPUG in 1957

The aged KPUG newspaper ad featured John Munroe, program director in the late-’50s. In fall 1958, Munroe took a hiatus from radio to teach school. A decade later, returning to broadcasting, he accepted a position at KGMI. Elaine Horn (the same Elaine who began at KVOS) hosted Party Line, a Monday through Friday show for women. Ed Triplett was the KPUG news director. Briefly, he moved across town to KENY. Then in 1960, he joined the staff of the Spokesman Review newspaper in Spokane.

KENY-AM Radio (later KBFW)

KENY was the new radio station in town. Debuting in 1958, it was licensed by the FCC as a daytime only radio station — required to sign-off the air each night at sundown (as early as 4:15 pm in the winter). Dual licensed to Bellingham and Ferndale, for a few years KENY maintained studios in both cities. KENY’s owner-manager, Tom Haveman, was born in Lynden and raised in Bellingham. Haveman was the student body president, and a senior at Bellingham High School, when Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941. The next year, he enrolled at Western. But not unexpectedly, Tom’s college education was disrupted by a four-year tour with the Navy Air Corps.

With the war over, and his military service complete, Haveman entered broadcasting. Starting out in Idaho, Tom gravitated back to the Pacific Northwest, working at KBRC in Mount Vernon and at KVOS in Bellingham. When 1958 rolled around, Tom founded KENY radio.

Early KENY

KENY’s format was fully dependent on local programming. There was no affiliation with a national radio network. The local announcers auctioned off merchandise provided by local sponsors, they hosted radio bingo and played mellow pop tunes. Listeners could tune in for the music and information heard on Spinner Sanctum, Supper Songs or the Kounty Show. Chuck Cavanaugh, Gary Vance, Clate Holm, Ted Beauchamp, Jack Pierce, Bill Lehr, Jack “Dailey” Bailey and station owner Tom Haveman were regulars on early KENY.

When Pop Ruled

In the 1950s, all three Bellingham radio stations were playing easy listening pop music. Any record that could be categorized as rock ‘n’ roll was avoided. Some of Bellingham’s old timers still retain fond memories of that bygone era. Bruce Day, a former Bellingham resident, loved listening to soft pop music on KPUG in the late -1940s and the ’50s.

“As kids, every night my six brothers and I tuned in to disc jockey Don Pinney. We could see the KPUG tower lights from our upstairs window on Superior Street in Bellingham. Pinney had such a quiet, soft voice and the music was very soothing. It was before Elvis and early rock ‘n’ roll. The music was great at bedtime. Pinney played artists like Teresa Brewer, the Browns (‘The Three Bells‘), the Ink Spots, Rosemary Clooney, Vic Damone, etc., before escalating to the Penguins and the Crew-Cuts [both sang ‘Earth Angel’], the Brothers Four, Johnnie Ray [‘Little White Cloud That Cried’], Frankie Lane and even Mario Lanza [‘Cara Mia’], et al.

“I am always amazed I can still remember most of the lyrics to all of those old songs. My brothers and I were so young, ranging in age from 4 to 14 years, that none of us were keen on Frank Sinatra, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway or any of the big bands or jazz musicians. That style was not for us,” Day recalled, “but we sure liked lots of the pop music Don Pinney played on KPUG.”

Don Pinney moved to Bellingham in 1949. Before that he’d been at an Idaho radio station owned by Jessica Longston. Older than most of KPUG’s deejays, Don left radio by 1960 and worked retail in downtown Bellingham (see newspaper clipping) until his retirement.

That’s a wrap for part 1 of this series. As the l950s were winding down, all of the Bellingham radio stations were sticking with mellow pop music playlists and shunning both early rock ‘n’ roll and Top 40. But the 1960s were on their way and change was in the air. Part 2 of this series is now available. In the early-1960s not one but two Bellingham radio stations would flip to Top 40 formats. Click HERE to read: The Road to Top 40: Bellingham – PT 2.

Thank yous and acknowledgements:

Dick Stark, Gary “Taylor” Bruno, Gary “Shannon” Burleigh, Jay Hamilton, Kirk Wilde, Steve West, Don Hedman Jr., Diane “Haveman” Puckett, Tom Cline (Mark Williams), Bill Hamelin, Bill Ogden, Dan Strode, Keith Shipman (WSAB), Dick Goodman

Click on the names below to learn more about these other Pacific NW broadcasters:

Danny Holiday (KPUG & KOL)

Dick Stark (KENY & KPUG)

Kirk Wilde (KPUG)

Gary Shannon (KPUG & KJR)

Mike Forney (KPUG)

Jay Hamilton (KPUG & KBFW)

Bob O’Neil & Marc Taylor (KPUG)

John Christopher Kowsky (KPUG)

Haines Faye & Rogan Jones (KVOS & KGMI)

Tom Haveman (KENY & KVOS)

Red Robinson (Vancouver B.C.)

Pat O’Day (KJR & KYYX Seattle)

Don Hedman (KJR & KAYO Seattle)

I really like this article. Can’t wait for part 2 and that Pearl Harbor broadcast.

Jeffrey..I have published part 2 of the Road to Top 40…mainly about KENY and KPUG…but not yet the 3rd detailed piece exclusive to early KVOS. Much of it is written but still a ways from publication. Many irons in the fire at this moment. Do you have a tie in to Bellingham? Or just interested in radio as it used to be?

Yes, after I posted the message I saw you had posted Part 2. The answer to your question is “both”. I grew up in Whatcom County. Dad talked a bit about listening to KVOS as a child- I listened to KPUG in the 60’s- then I heard Boss Radio CKLG. And of course everybody remembers Haines Fay.

Thanks…Interesting info. I am sure you will like the more detailed history of KVOS….when I have it done

Pat…I plan to do a similar piece with Unusual’s history. Including audio clips.

Steve:

That’s a lot of history. Brings back many memories. Lots of fun!

I am glad you like it Mike. The upcoming second part has some pretty cool history in it too. Including an aircheck of all the original top 40 jocks at KPUG….all of whom had great careers in and out of radio.

A comprehensive history of Top 40’s beginnings and Bellingham radio. Well done!

Jason…I have part 2 close to ready. And I plan to do the full details of KVOS including audio back to the 1920s in a future article. KVOS was a way more interesting story than I had realized…some of it in this article.