KVOS radio was born in Seattle during the Roaring 20s. The “Great War” had ended in 1918. Silent Cal Coolidge was the president and the soon to be Great Depression was on the horizon. Prohibition (the 18th Amendment) had been the law of the land for six years. Bootlegging was rampant nationwide. Al Capone and his Chicago mob were getting rich off the illicit booze trade and the Pacific NW had its share of such goings on as well: Notorious rum-runner Roy Olmstead, who illegally transported and distributed Canadian liquor in the Puget Sound area, was a cop and a radio station owner. Olmstead’s radio station sent coded messages — offloading instructions for the contraband — to cohort rum-runners in speedboats laden with booze and moored off the coast of Washington. {1}

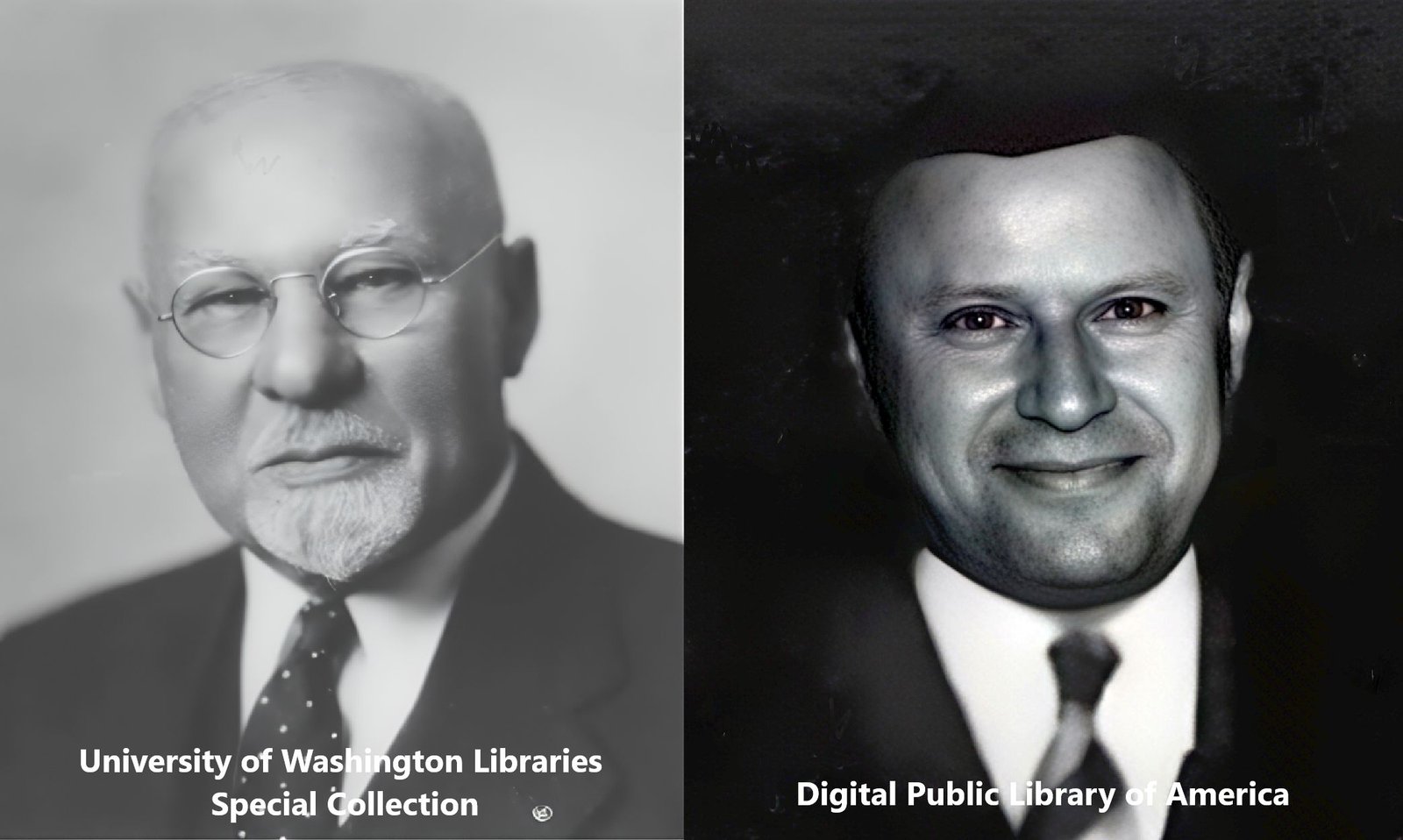

Louis Kessler

At year end 1926, KVOS debuted in Seattle becoming only the eleventh radio station in the Puget Sound region. KVOS was the dream of 30-year-old Louis Kessler. Born and raised in Seattle, Kessler had served as a U.S. Army bugler in France during the First World War. Lou had prior experience as an entertainer — musician, actor, public speaker and comedian — but not as a business owner. Kessler’s run in the radio business would be short-lived, but even after his experiment with radio ownership failed; Kessler had a productive life in the private sector and in government. {2}

KVOS was a shoestring operation and Kessler served as a jack of all trades: president, general manager, program director, salesman and, for a long time, the only staff announcer. Initially, KVOS went on-the- air for two hours in the early evening: Kessler spun 78 RPM records but, after two weeks, he expanded his hours to incorporate live musicians into the programming. Even then, KVOS retained a very limited broadcast schedule, transmitting for a couple hours late mornings and again in late afternoons into the evening. KVOS was dark a lot more often than it was on-the-air.

Voice of Seattle, Inc.

Kessler selected the KVOS call letters, all except for the “K” at the front which was assigned by the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) to designate that the station was located west of the Mississippi River. The FRC would be replaced by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in June 1944. Lou said the call sign stood for “Kessler’s Voice of Seattle.” On July 26, 1927, seven months after KVOS had debuted in Seattle, the Seattle Daily Times published a legal notice referencing the formation of a new company called Voice of Seattle, Inc.

Corporate Officersayaa

Voice of Seattle, Inc. listed three incorporators: Louis Kessler, Herman Kessler (Lou’s father, a Seattle clothier), and Sol Esfeld (a civic leader and a successful Seattle insurance broker). The Kessler and Esfeld families were friendly with one another and both prominent in Seattle’s Jewish community and B’nai B’rith. Esfeld was a corporate officer; however, it appears that he did not hold a financial stake in the company. Newspapers in Seattle also reported that broadcasting engineer L.L. Jackson was Kessler’s business partner, yet FRC records had Louis Kessler as the station’s sole licensee. Jackson might have helped get the transmitter and the studio on-the-air, but he was not a co-licensee, nor was he a registered stockholder in Voice of Seattle, Inc.

Taking Stock

Voice of Seattle, Inc. issued 150 shares of stock valued at $15,000. Herman Kessler held 25% of the company. Lou Kessler owned 35%, and the largest stockholder, with a 40% share, was Seattle businessman Albert Lobe. Lobe came from an entrepreneurial Bellingham family. His money was from mining, real estate/commercial development, retail sales, automobile parts manufacturing and propagating tulip bulbs he’d imported from Holland and grown locally for U.S. distribution.

In 1914, Al Lobe and his wife Lettie founded Lobe’s Suit & Cloak, later renamed Lobe’s Ready to Wear. Lobe’s Bellingham store was the largest women’s apparel outlet north of Seattle. After five years of ownership, the Lobes sold their mercantile and moved to Oakland where Al operated a company that manufactured geared axles for early Ford vehicles. Circa 1921, Al and Lettie left California and settled in Seattle, where they were living when Albert invested in Voice of Seattle, Inc. Better known in Bellingham than Albert was his brother Carl, who’d in 1905 accepted an entry level job at the Bellingham Bay Furniture Company (B.B. Furniture). Over the years, Carl Lobe climbed the corporate ladder to become the owner of the prestigious furniture store.

On-the-Air in Seattle

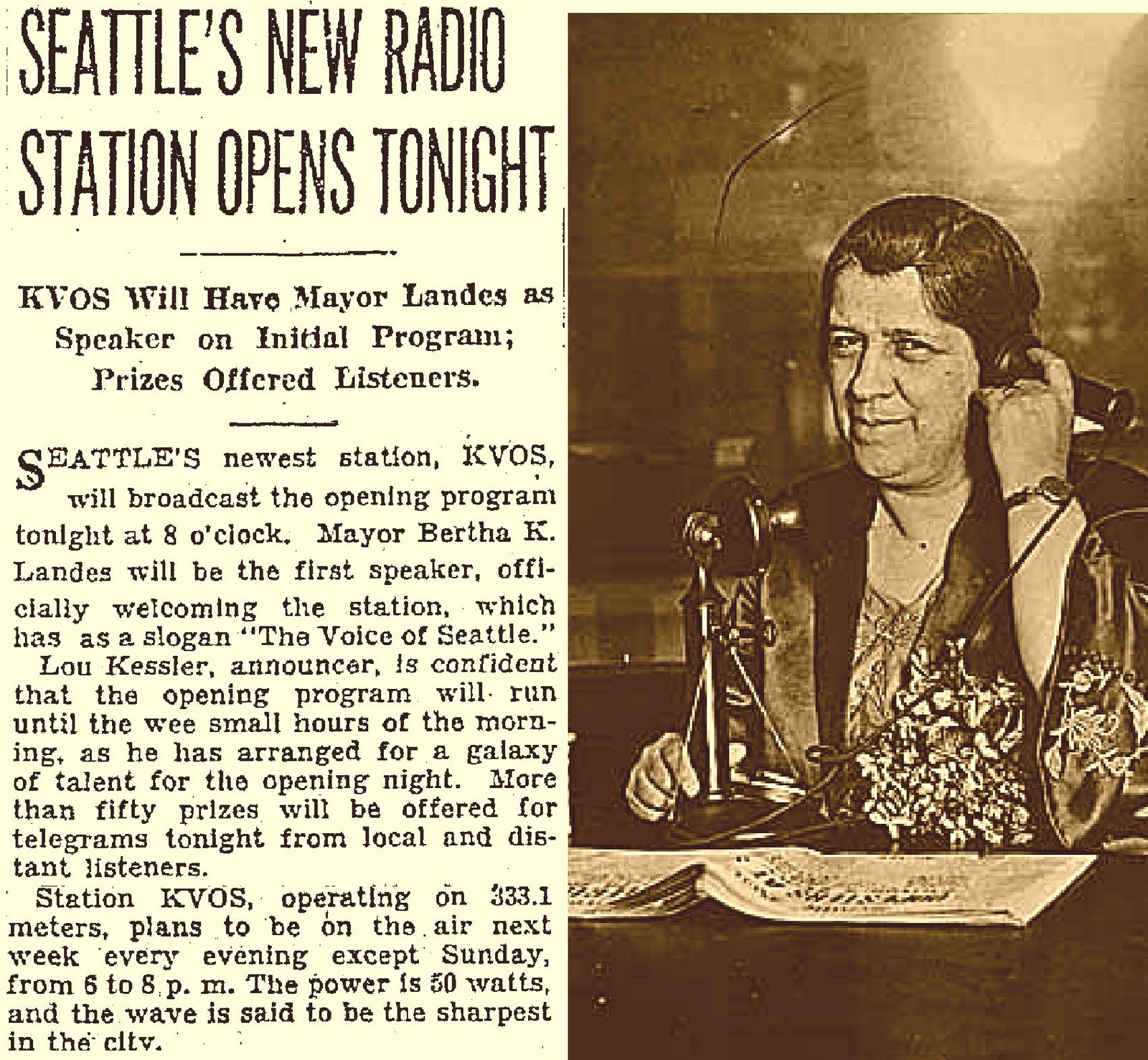

The December 11, 1926 inaugural broadcast of radio station KVOS was highly touted in Seattle newspapers. There was a welcoming speech by Seattle Mayor Bertha K. Landes. A straight talker, and an enthusiastic supporter of Prohibition, Landes was the first female to be elected mayor (1926-1928) of a large American city. Women had been elected to similar positions in smaller towns in the U.S.A., but never before in a major city.

Seattle Studios

The KVOS studio, transmitter and antenna were first located on the rooftop of the Rosita Villa Apartments on Queen Ann Hill. Six months later, Kessler moved his operation downtown to the swanky New Washington Hotel at Second Avenue and Stewart Streets. That downtown location made KVOS more visible to potential listeners and to the community, but financial problems persisted. KOMO, KJR, and KVI were well-established Seattle radio stations with deep pockets that made life difficult for startup KVOS.

Radio’s Uncertain Future

In the 1920s, the jury was still out as to whether or not wireless operators (a nickname for early radio broadcasters) had a future. Technical problems with the new electronic gadgetry were abundant. At the transmitting end, engineers had to string together banks of car batteries to keep the current-guzzling direct current powered vacuum tube transmitters operating. Even then, as the batteries faded, a radio station’s transmitter might also fade away into the ether. At the listener’s end, radio receivers tended to be large and not very portable. And they too were dependent on battery power: Receivers that plugged into wall outlets didn’t come along until the late 1920s. Another complication, early radio receivers required a ground connection to a water pipe or to a metal rod driven into the earth.

The first radio receivers were simplistic crystal sets. In the audio clip, gleaned from a 1961 program that acknowledged KVOS’ more than 30 years in business, longtime KVOS announcer Haines Fay described the big differences between 1960’s radio receivers and the crystal sets listeners relied on in the ’20s.

Haines Fay, Aug. 1961 broadcast: Center for Pacific NW Studies, “1927 Days,” Rogan Jones Papers, Western Libraries, Archives & Special Collections, Western Washington University (Running Time: 1:10)

Disturbing Interference

Federal regulations were necessary to avoid overpopulation and chaos on the radio band. But some of the FRC’s preliminary rules were problematic for the fledgling industry. As examples, many radio stations were limited to very low power outputs: 50 to 100 watts was typical. Even with only a few radio stations in the ’20s, low power signals were prone to mechanical and electrical interference. Equally annoying, the FRC regularly tinkered with broadcaster’s dial positions. A weak and interference prone signal that flipped around on the dial made it difficult to build loyal listenership.

Focusing on changes at KVOS, the station began with 50 watts output at a frequency of 333.1 meters (900 kHz). Six months later, in mid-1927, the frequency was changed to 209.7 meters (1430 kHz), but the power output remained the same. In fall 1928, KVOS moved to 1200 kHz with a power boost to 100 watts. For the remainder of Kessler’s reign, the power and the frequency remained stable.

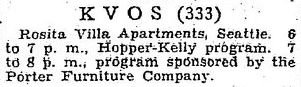

The various frequency changes, applicable to Kessler’s years of ownership, are seen in these clippings from the Seattle Daily Times and the Bellingham Herald. Note that in1928, newspapers began referencing radio frequency in kilohertz vs. old-fashioned meters.

Paying the Bills

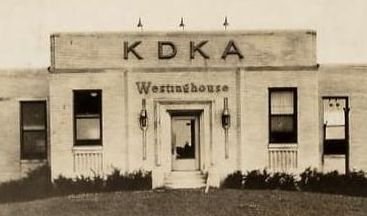

Technical deficiencies, regulations and overall unpredictability presented challenges for early broadcasters. But the bigger concern was trying to figure out how to pay the bills. Even before the Great Depression hit with full force in 1929, generating revenue from a radio station was difficult. It is not a mystery why some of the first radio stations in the country were built by companies that manufactured and/or sold radio receivers. The concept was that the more radio stations in the market place, the more demand there would be for radio receivers. America’s first radio station, KDKA in Pittsburgh, was owned and built by Westinghouse. KFC, a short-lived Seattle radio station (Dec. 1921-Jan. 1923) was owned by the Northern Radio and Electric Company. KFC was among the first radio stations in the Northwest and it was housed at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer building.

Technical deficiencies, regulations and overall unpredictability presented challenges for early broadcasters. But the bigger concern was trying to figure out how to pay the bills. Even before the Great Depression hit with full force in 1929, generating revenue from a radio station was difficult. It is not a mystery why some of the first radio stations in the country were built by companies that manufactured and/or sold radio receivers. The concept was that the more radio stations in the market place, the more demand there would be for radio receivers. America’s first radio station, KDKA in Pittsburgh, was owned and built by Westinghouse. KFC, a short-lived Seattle radio station (Dec. 1921-Jan. 1923) was owned by the Northern Radio and Electric Company. KFC was among the first radio stations in the Northwest and it was housed at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer building.

Surviving off the spoils of selling radio receivers worked for some manufacturers and distributors, but it was a non-starter for independent operators. A viable option had been discovered in the 1700s. That’s when newspapers and magazines began selling print advertising and subscriptions. Subscriptions were off the table, anyone with a receiver could listen to the radio. Spoken word advertising, presented on-air by a radio announcer, seemed to have revenue potential. But radio was not an easy sell. It was seen as an amusing novelty, a curiosity and a non-essential that held little intrinsic value in the minds of the titans of business and industry.

With tenacity, and pushing forward despite the odds, some radio stations saw dribs and drabs of paid and bartered ad revenue begin to trickle in. The first radio ads were often sold as full program sponsorships. The shows and the sponsors could be cross-promoted in local newspapers. Two days after he signed on-the-air in Seattle, Kessler had two sponsors: Hopper-Kelly Music and Porter Furniture. It is unknown if the sponsors paid cash for the advertising or if they were bartered “trade out” deals.

Roaring ’20s Radio

In the first half of the Roaring ‘20s, radio programming was by necessity of local origin (the first national network didn’t come along until NBC in 1926). Before networks, broadcasters ran music, hometown farm reports, lectures, poetry readings, politics, religion, quacks hawking miracle cures and the occasional news story. Music was the most popular programming and it was available in only two formats: a staff person played 78 RPM phonograph records, or local musicians performed live in-studio. The latter was more costly, but it was the preferred option since the sound quality of radio microphones far exceeded the fidelity of tinny and often scratched 78 RPM records.

Doing it his Way

Kessler signed on hoping to compete with Seattle’s market leaders KOMO and KJR. For the first two weeks, he spun records for a couple hours most evenings. He often grouped together recordings that fit with a theme: big bands, dance tunes, show songs or music for kids. The “Housecleaning Hour of Music” was one such program — peppy jazz to help motivate housewives. Kessler would play requests if listeners would make the effort to write them down and mail them in.

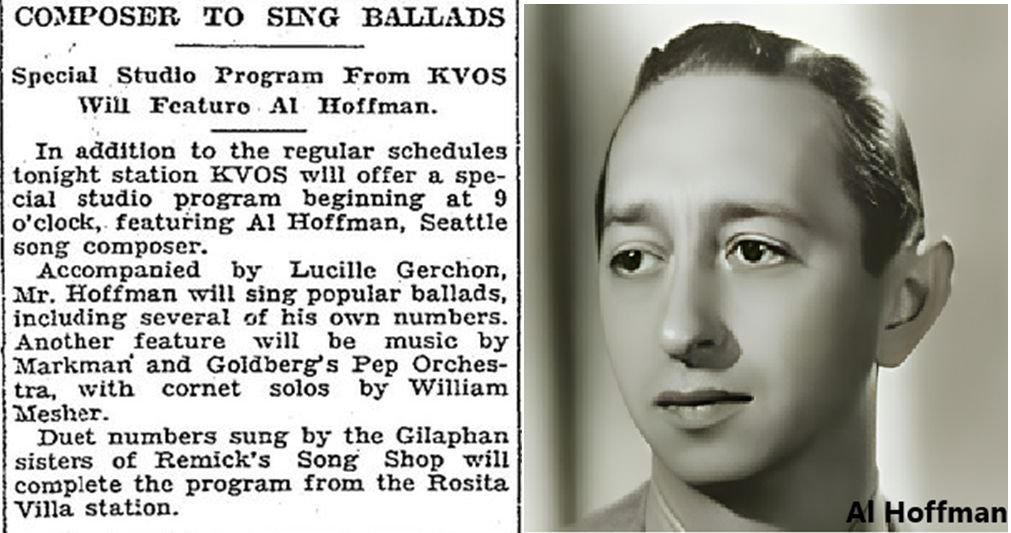

About two weeks after KVOS’ debut, Kessler offered his first live in-studio musical program. It featured up and coming Seattle composer, singer and drummer Al Hoffman. Later Hoffman would become a successful songwriter and co-composer of hits for Perry Como, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Patsy Cline and for Walt Disney’s classic 1950’s movie “Cinderella.” The catchy No.1 tune “Mairzy Doats” by the Merry Macs (1944) and later the “Hawaiian Wedding Song” by Andy Williams (1958) and three years later recorded by Elvis, were songs Hoffman co-wrote. In 1984, he was posthumously elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

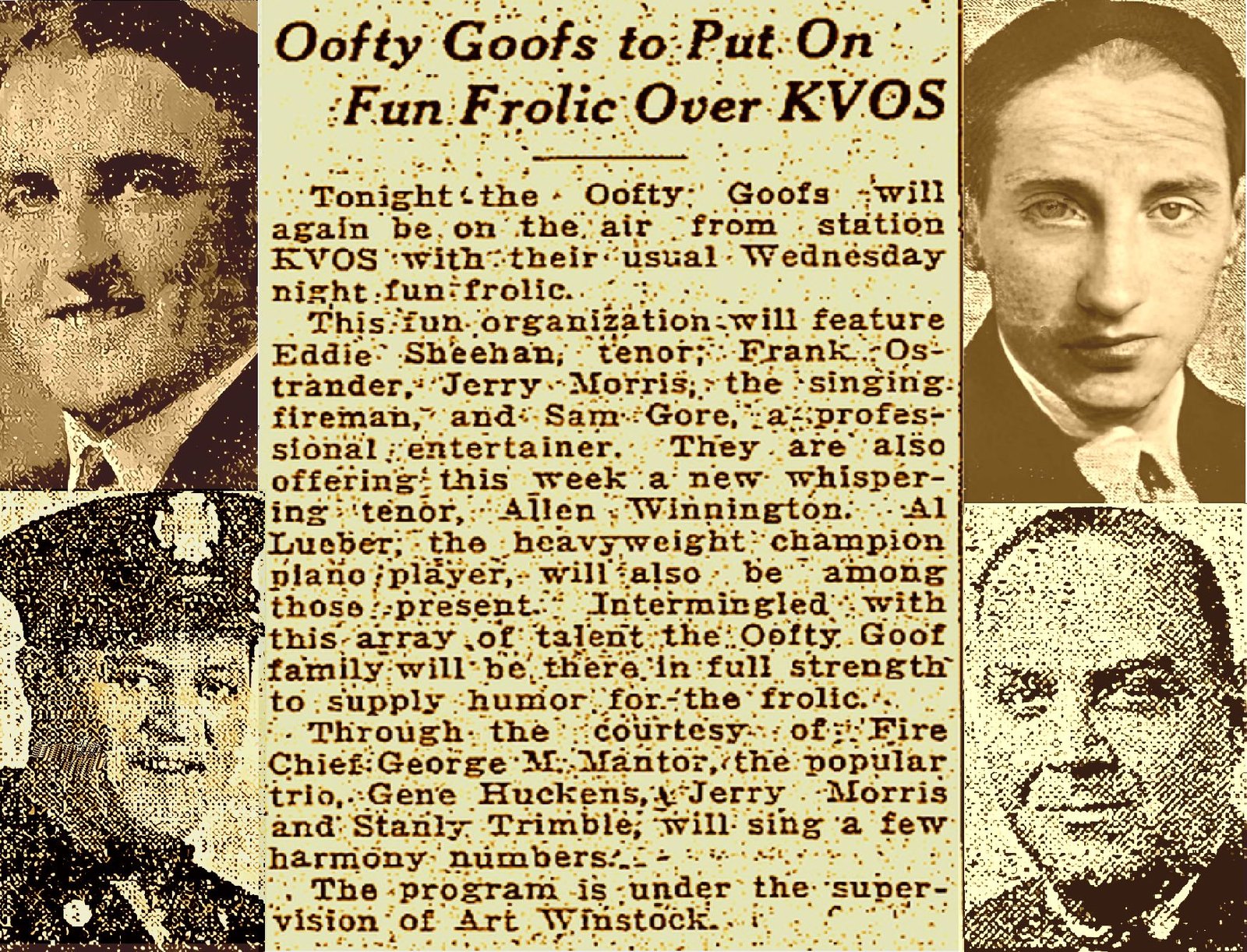

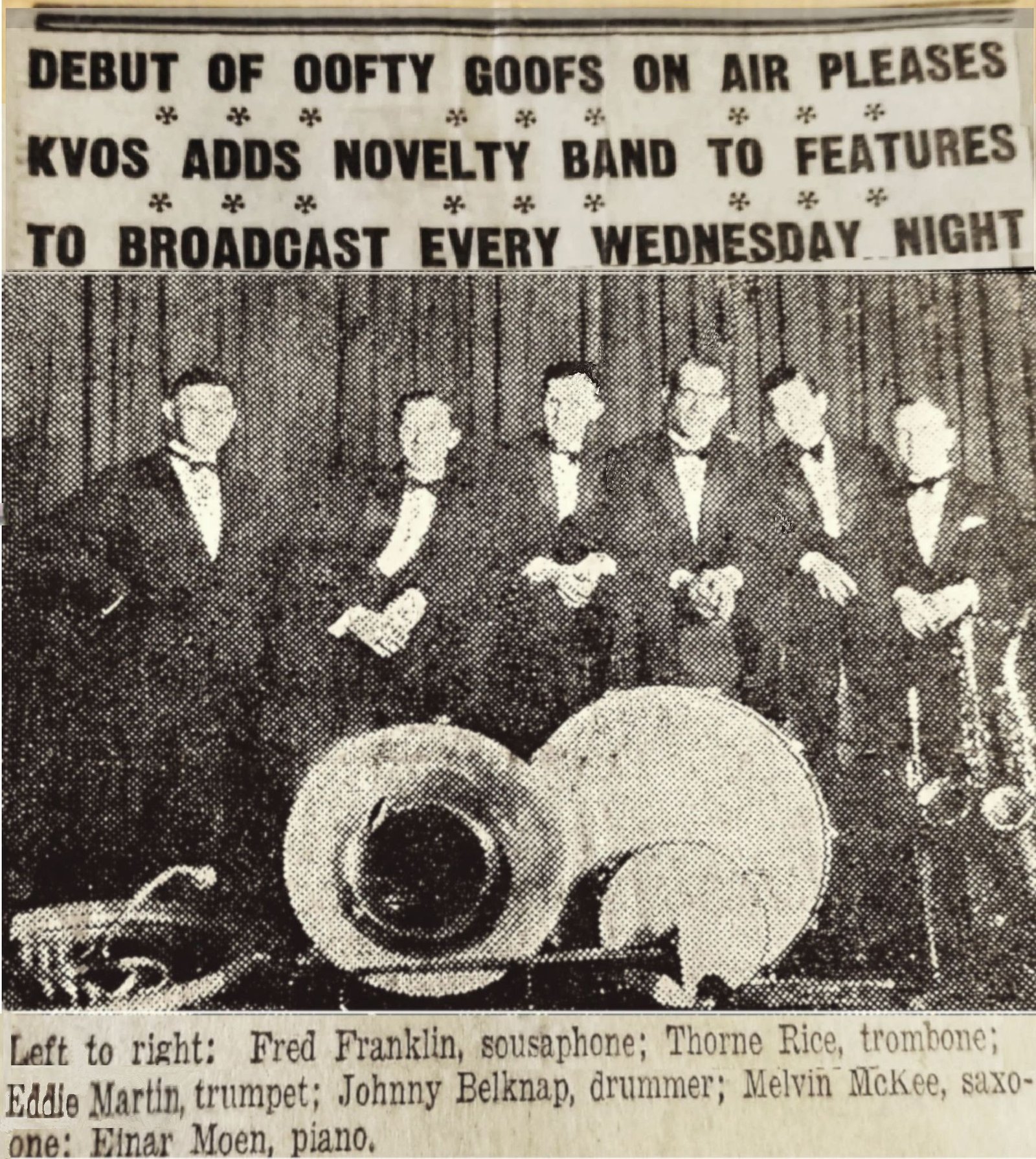

When the Oofty Goofs Prevailed

Kessler was broadcasting from Seattle when he conjured up the musical variety show known as the “Oofty Goof Frolic.” Billed as a Scandinavian musical spoof, it would be the only show from Kessler’s Seattle days to survive his soon to be move to Bellingham, WA. In the late ’20s, the Seattle Daily Times promoted the Oofty Goofs in a news story. The publicity photos of some of the stars also came from Seattle newspapers. At the top right, that’s “whispering tenor” Allen Winnington. “Whispering tenors” seemed to be a big deal 100 years ago. Now they belong to a long forgotten singing craze.

Kessler’s enthusiasm for live on-air entertainment began with a burst of activity, but it did not keep up the momentum. Live talent required compensation and the expense did not fit well with KVOS’ limited finances. Tightening his belt, Kessler returned to playing mostly 78 RPM records. The live talent didn’t go away entirely, but local musicians were appearing less frequently. Some of the artists who were associated with KVOS during the station’s Seattle days were drummer Bill Perry and his dance band, University of Washington pianist Marion Elwell, UW soprano Alberta McPhie, clarinetist Nick Carter, and Seattle’s Bethel Temple Orchestra and Choir.

Quackin’ for Cash

As Lou Kessler discovered, employing live in-studio musicians required an outlay of cash or barter deals. Sometimes performers agreed to work free or at little cost if they could promote their services on-air or if they received a portion of the goods and services that were “traded-out” with the station’s advertisers.

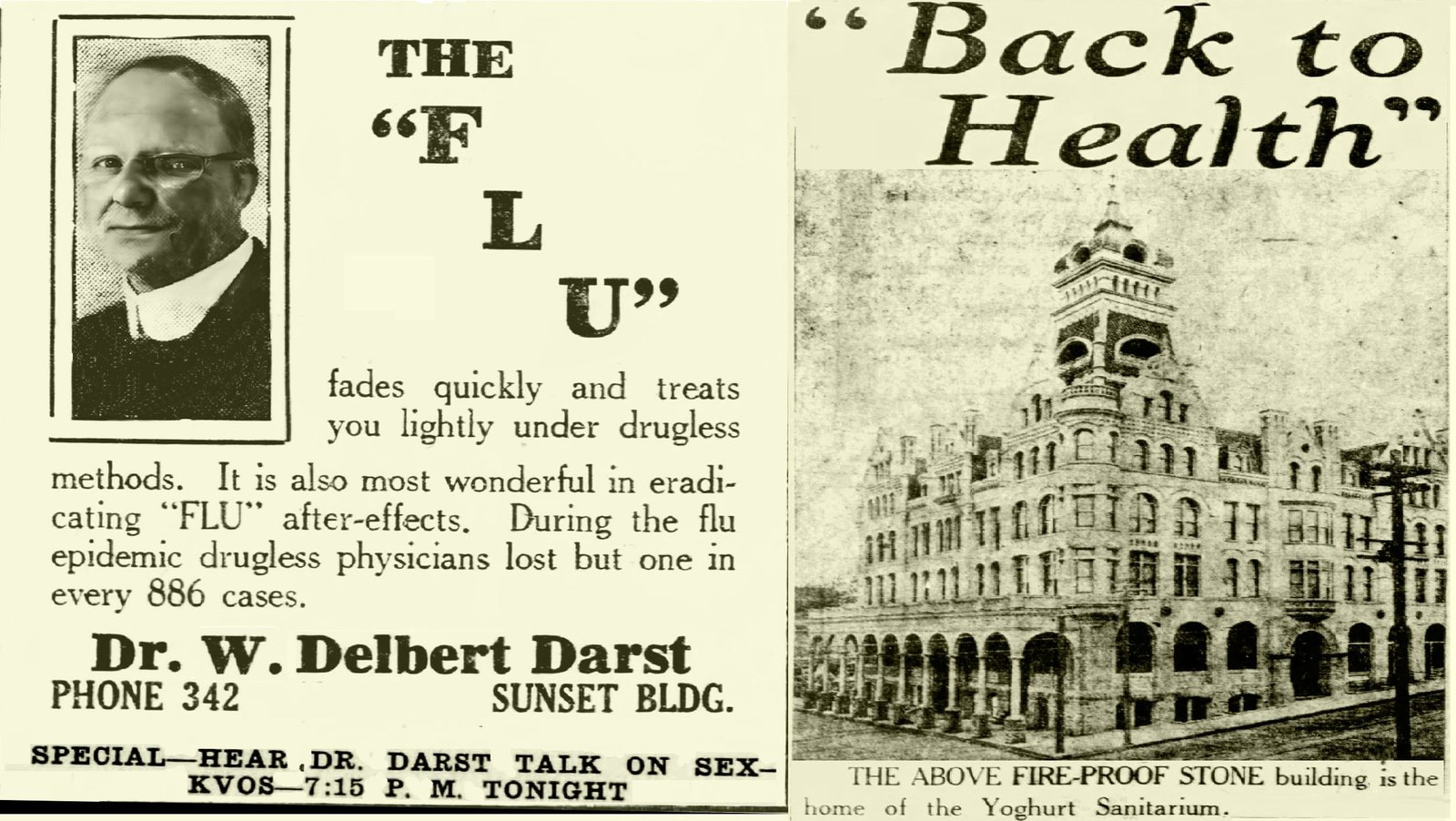

More lucrative for a cash deprived radio station was selling paid programming: A sponsor would shell out money for an opportunity to launch into an on-air spiel. That naturally led to the “Quack” market, where unlicensed medical practitioners sold their sketchy remedies, not unlike the questionable medical advice and products currently promoted on YouTube and on social media. In the 1920s and ’30s, unregulated snake oil salesmen bought lots of airtime on local radio. When KVOS was in Seattle, the station aired the Mar-Va-Sol radio lectures: A pitchman would promote a dubious miracle elixir that supposedly treated rheumatism, neuritis and high-blood pressure.

National Talent on Seattle Radio

The smaller Seattle broadcasters got a lucky break when the Brunswick and Columbia Record labels released a number of 78 RPM records featuring Seattle and West Coast artists. Kessler and the other little guys didn’t have the financial means to entice Seattle’s biggest musical stars to perform live, but they could play the records. Vic Meyers, a favorite live performer at KJR, was a Seattle-centric recording artist who appeared on national record labels. Meyers, best known nationally as an orchestra leader, was prolific. From 1919 to 1929 he and his orchestra recorded more than 20 singles.

The smaller Seattle broadcasters got a lucky break when the Brunswick and Columbia Record labels released a number of 78 RPM records featuring Seattle and West Coast artists. Kessler and the other little guys didn’t have the financial means to entice Seattle’s biggest musical stars to perform live, but they could play the records. Vic Meyers, a favorite live performer at KJR, was a Seattle-centric recording artist who appeared on national record labels. Meyers, best known nationally as an orchestra leader, was prolific. From 1919 to 1929 he and his orchestra recorded more than 20 singles.

Meyers was much more than just an accomplished musician. In Washington State he was dubbed the “Clown Prince of Politics.” Vic leveraged his fame as a fun-loving jokester into a long and colorful political career. There was the time he campaigned from a beer wagon during Prohibition and on another occasion he attended a campaign event outfitted as Mahatma Gandhi with a goat in tow.

Meyers ran as a democrat and was elected Washington State Lieutenant Governor in 1932. Reelected five times, he lost the seat in the Dwight Eisenhower GOP landslide of 1952. Returning to music in the interim, he soon jumped back into politics. Elected to the position of Washington State Secretary of State in 1956, Meyers was re-elected four years later. In total, Vic served eight years as Secretary of State. He and his Hotel Butler Orchestra were the first to record the University of Washington’s fight song “Bow Down to Washington.” Click below to listen to this favorite on the west side of Washington State.

“Bow Down to Washington,” 1928 release, Vic Meyers & his Butler Hotel Orchestra (Running Time: 2:59)

Bing-go

According to musical lore, Vic Meyers said that one time a “jug-eared young crooner” auditioned for a singing role with his orchestra. After the audition, Meyers told the kid to “get out of the business and to look into some other profession.” That young crooner from Spokane was Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby Jr., who has since been anointed as one of the top stars of the 20th Century. Before hitting it really big in 1931, Crosby and his singing partner, Al Rinker, performed as a duo and then as two-thirds of the Rhythm Boys — a trio comprised of Crosby, Rinker and singer/songwriter Harry Barris. They sang on more than two dozen records by Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra. Perhaps the biggest star to ever come from the Evergreen State, Bing’s first solo was in 1927 on Whiteman’s “Mississippi Mud.” Bing and the Rhythm Boys appeared with Whiteman in the 1930 Universal motion picture “The King of Jazz,” which was one of the earliest color films. In the video below, Bing and the Rhythm Boys begin with “Mississippi Mud” and quickly segue into their 1929 pop hit “So the Bluebirds and Blackbirds Got Together.”

Seattle Bands & Orchestras on the Radio

Several top Northwest bands and orchestras appeared live on Seattle radio stations. Along with Vic Meyers and his orchestra, the list of elite performers included Cole McElroy’s Spanish Ball Room Band, Jackie Souders and his Butler Hotel Band, Eddie Harkness and his Olympia Hotel Orchestra and “Toots” Bates and his Highway Pavilion Orchestra. McElroy, Souders and Harkness all had recording contracts with national record labels. Click on the video to listen to some of the songs recorded by these leading West Coast artists.

Destination Bellingham

KVOS was undercapitalized from the get-go and Kessler always struggled financially. He couldn’t compete in a large market ripe with established and better funded radio stations. His efforts at selling radio time landed a few sponsors, but an insufficient number to avoid chronic money problems. Less than a year after the station’s first broadcast from Seattle, the FRC approved a request from Kessler that he be allowed to move his radio station 90 miles north to Bellingham, WA.

In Bellingham, a small and less competitive radio market, Kessler hoped KVOS would flourish. At the time, he had the only radio station in town, although KVOS wasn’t Bellingham’s first radio station. That distinction goes to defunct KDZR, operational 1922 to 1925, and owned by the then combined Bellingham Herald/Bellingham Reveille newspapers. KDZR broadcast from the Bellingham Radio Shop on Prospect Street downtown. When KDZR folded, the ego-deflated newspaper executives in charge disparagingly described radio as a “fully inadequate and impractical business.” Below is a KDZR program guide that ran in the Bellingham Herald more than 100 years ago.

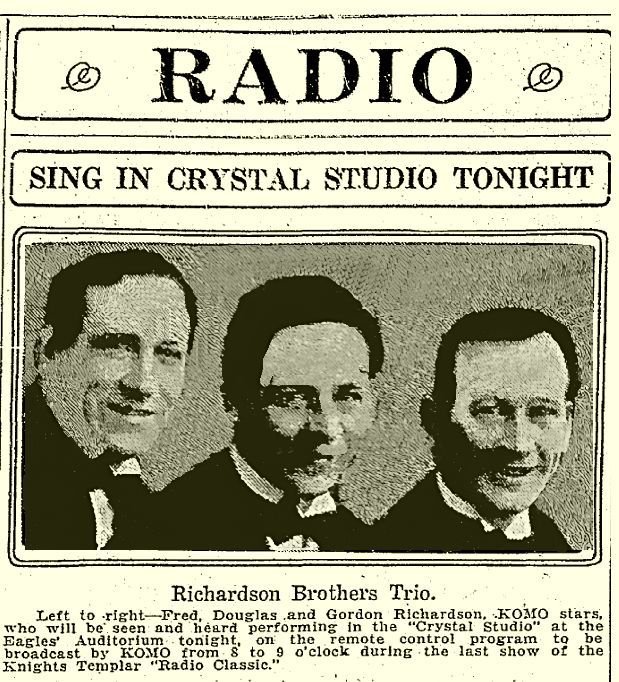

The Richardson Brothers

Five days before KVOS debuted in Bellingham, Kessler said he’d hired Douglas Richardson, a star on Seattle radio, as a staff artist. Richardson, a tenor, had been an audience favorite on KOMO, KJR and at lesser knowns KFOA and KTCL. Richardson had a West Coast deal with Columbia Records. Radio entertainers weren’t particularly well paid to begin with, so Richardson’s arrangement with Kessler wasn’t exclusive. The singer was allowed to perform at other radio stations, including in Seattle, Portland, California and Idaho.

Doug Richardson’s two older brothers were also accomplished tenors. Shortly after Doug was on board at KVOS, Gordon and Fred Richardson inked deals with Kessler. The singing Richardson brothers were versatile — able to perform solo, as a duo or as a trio. A bonus, Gordon and Fred agreed to sit-in as radio announcers. That helped Kessler who, up until that point, had been the station’s only full time announcer. Gordon Richardson would host “Ask Me Another”: a question and answer contest that pitted the knowledge of one family member against another. A live musical show, “Gloom Killers,” featured the vocal talents of both Gordon and Fred Richardson.

Halloween 1927

On Halloween Eve, Oct. 31, 1927, KVOS launched its inaugural broadcast from Bellingham. Local jazz and classical musicians performed live and the gala celebration had the standard welcoming speeches by Bellingham’s dignitaries. John A. Kellogg, the mayor, spoke as did Pat E. Healy from the Chamber of Commerce and Dr. Charles H. Fisher the President of the Bellingham Normal School (now Western Washington University).

On Halloween Eve, Oct. 31, 1927, KVOS launched its inaugural broadcast from Bellingham. Local jazz and classical musicians performed live and the gala celebration had the standard welcoming speeches by Bellingham’s dignitaries. John A. Kellogg, the mayor, spoke as did Pat E. Healy from the Chamber of Commerce and Dr. Charles H. Fisher the President of the Bellingham Normal School (now Western Washington University).

Musicians, who performed that first night, were the aforementioned Doug Richardson; local soprano Dorothy Frank; the Tulip Trio (piano, violin and cello); Einar Moen on piano and the Jay Curtis Band. Curtis’ band was a top draw in Whatcom County, performing at grange halls, dance halls, ballrooms and restaurants, from 1925 until 1941. Einar Moen, who would become KVOS’ best known musician, was the pianist with the Jay Curtis Band (in the bottom photo of the Curtis Band, Moen is 2nd from the right and Jay Curtis is 6th from the left). The newspaper clipping ran in the Bellingham Herald on Oct 29, 1927.

Memories of a Radio Star

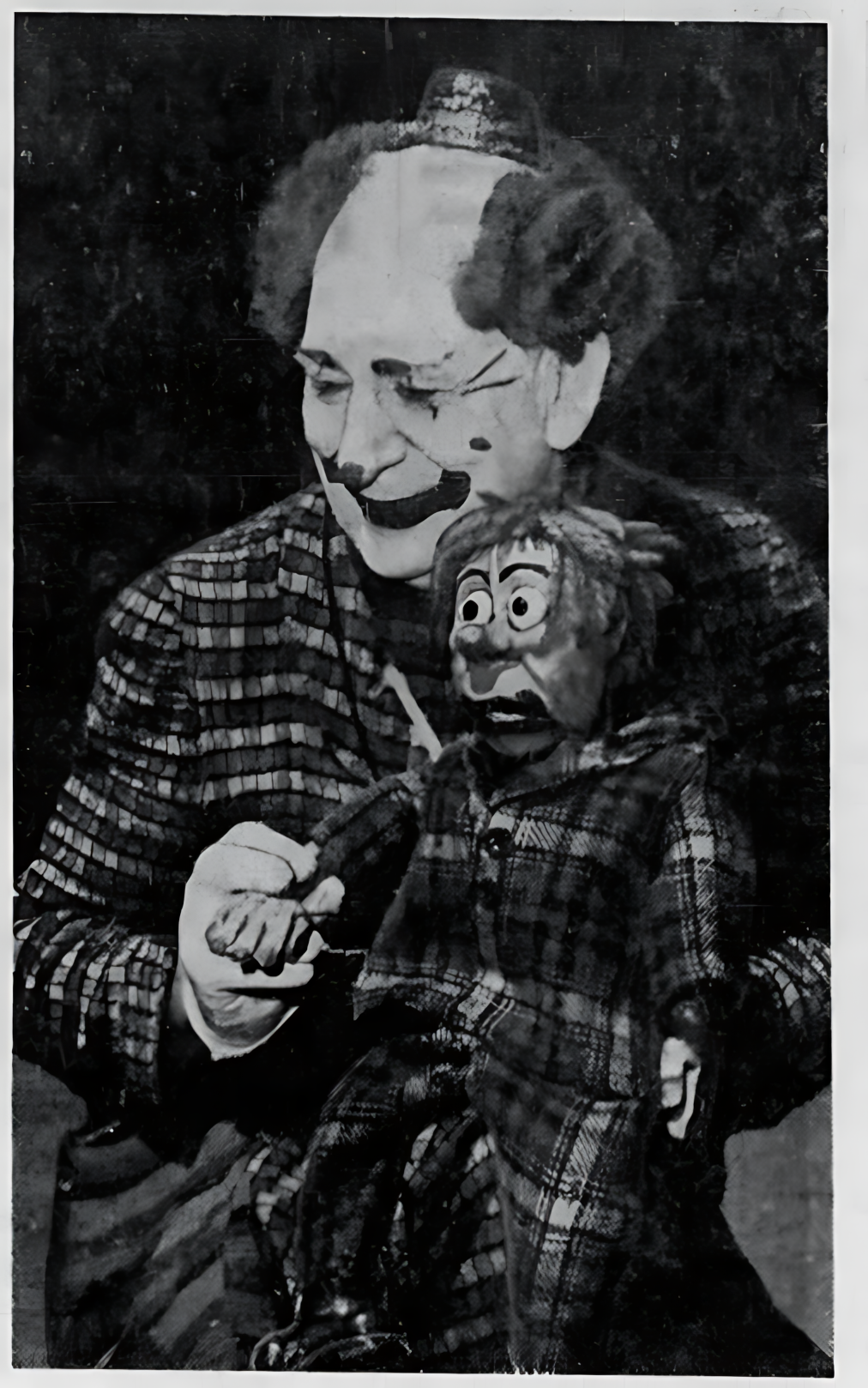

It is unclear how often Douglas Richardson actually performed on KVOS. At his peak, in the late 1920s, he was the “Northwest’s most famous radio singer.” Richardson held that title until he relocated to the Bay Area, in autumn 1929, where he was hired as a staff singer for the NBC Radio Network. During the depression it became increasingly difficult for Richardson to make a living by singing on the radio. In 1933, he left the business to take his chances in Vaudeville and Hollywood. Richardson sang, danced, worked as a singing waiter, co-owned a nightclub and, during WWII, he toured with the USO. Decades later, he’d return to Seattle — not as a singer, but as the official clown at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. {3}

is unclear how often Douglas Richardson actually performed on KVOS. At his peak, in the late 1920s, he was the “Northwest’s most famous radio singer.” Richardson held that title until he relocated to the Bay Area, in autumn 1929, where he was hired as a staff singer for the NBC Radio Network. During the depression it became increasingly difficult for Richardson to make a living by singing on the radio. In 1933, he left the business to take his chances in Vaudeville and Hollywood. Richardson sang, danced, worked as a singing waiter, co-owned a nightclub and, during WWII, he toured with the USO. Decades later, he’d return to Seattle — not as a singer, but as the official clown at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. {3}

Local recordings from the early days of KVOS are non-existent. However, a few copies of Douglas Richardson’s five 78 RPM singles on Columbia Records are still around. With the tight timeline between his record releases (1926- ’27) and his stint at KVOS (fall 1927) we’d assume that some of the songs were part of his repertoire at KVOS. Richardson’s style has been described as “typical 1920’s melancholic pop with a piano accompaniment.” Click on the audio player to hear Douglas Richardson’s first single: “Song of the Wanderer (Where Shall I Go)” followed by the B side “New Moon.”

Douglas Richardson: “Song of the Wanderer (Where Shall I Go?)” and “New Moon” released Sept. 1926 (Running Time: 5:51)

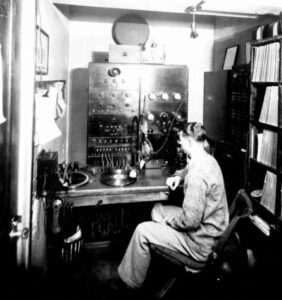

Hotel Henry

During Kessler’s time in Bellingham, the KVOS studio, offices, transmitter and antenna were located at the Hotel Henry on the corner of Holly Street and Elk Street (now State Street). The old Hotel Henry building still stands today, but it was turned into the Bellingham YMCA in 1944.

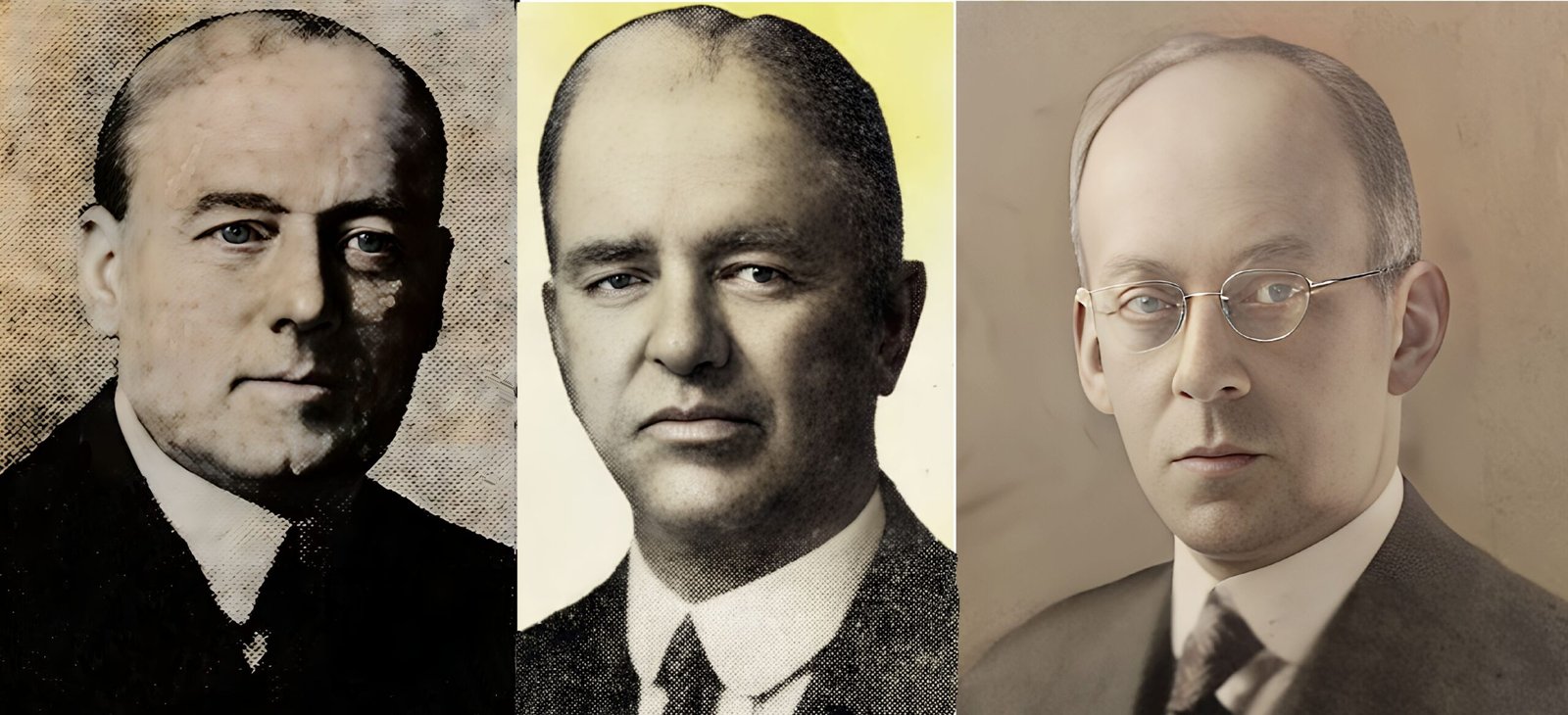

Mount Baker Radio Station

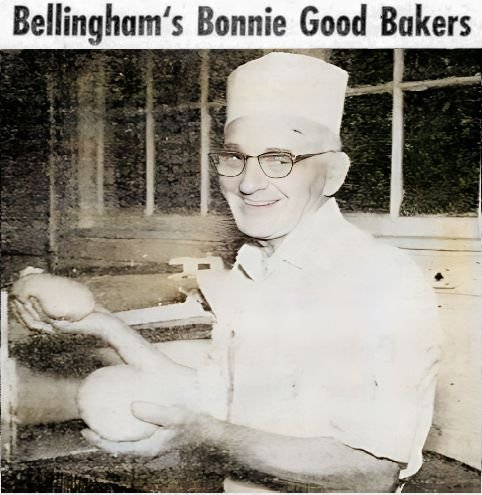

The KVOS call letters were unchanged in Bellingham, but the descriptor “Voice of Seattle” was retired. KVOS was re-branded as the “Mount Baker Radio Station,” a reference to a nearby mountain peak and ski area. Anyone who was old enough to have met Lou Kessler at the time, nearly 100 years ago, is long gone. Yet back in 1960 at a banquet celebrating KVOS, one speaker was 70-year-old retired baker Jake Wheeler. Jake recalled seeing Lou Kessler outside the Hotel Henry in the late ’20s. He said he was still trying to figure out why, after relocating to Bellingham, Kessler had stuck with the call letters KVOS instead of updating to KVOB for “Kessler’s Voice of Bellingham.”

Jake Wheeler from the Rogan Jones Papers, “1927 Days,” Center for Pacific NW Studies, Western Libraries, Archives & Special Collections, Western Washington University. (Running Time 1:37)

When Amateurs Entertained

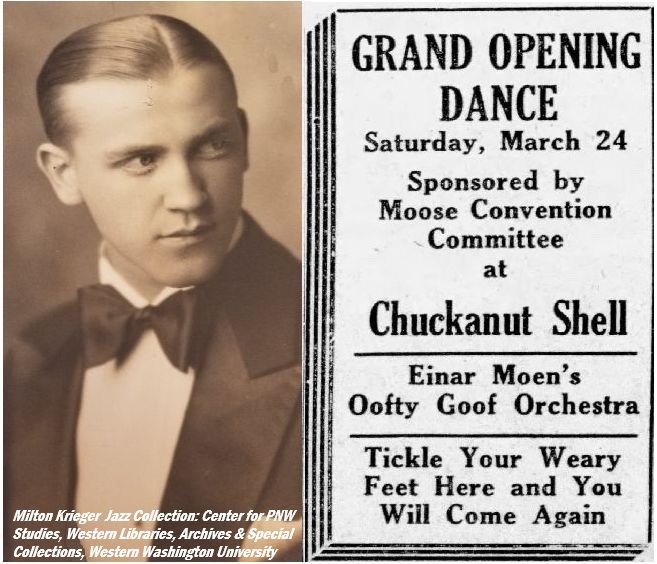

That old Bellingham Herald clipping (above) had been carefully cut out and saved by keyboardist Einar Moen. Kessler planned to present more live talent, and to rely less on 78 RPM records. First thing Lou did, he resuscitated the “Oofty Goof Frolic” that had aired in Seattle. But the show was re-cast with Bellingham talent. Moen got the title “chief fun-maker” and leader of the Oofty Goof Band (sometimes called the Oofty Goof Orchestra). Einar Moen was important in the early history of KVOS, affiliated with the station for 21 years (into the late 1940s), he survived the depression era financial crisis and worked with two different radio station owners. Moen played the piano when he performed on KVOS, but he became proficient on the organ in the mid-sixties when the owner of Sherman Clay Music asked him to provide both piano and organ lessons for their customers. Moen was one of only a few organists to perform concerts on the giant Wurlitzer pipe organ at Bellingham’s historic Mount Baker Theater.

Cultivating the Oofty Goof Band

Many of the young musicians in the Oofty Goof Band, as well as other entertainers heard on KVOS, had whet their appetites for music in the Bellingham Boy’s Juvenile Band. Forty to sixty members strong, the Juvenile Band got its start in the early ’20s, providing boys with a wholesome way to occupy time while they learned to play musical instruments. Well-funded and supported by various civic organizations, the Juvenile Band played and competed locally, regionally and even across the border in Canada. As a youth, Einar Moen participated in the Juvenile Band and he credited it for his success as a musician. In the early 1990s, Einar was interviewed by fellow musician and high school music teacher North Storms. Moen talked about the Bellingham Juvenile Band and the early days of KVOS radio.

Einar Moen from the Milton Krieger Collection of Jazz in Whatcom County. Center for Pacific NW Studies, Western Libraries, Archives & Special Collections, Western Washington University. Interviewer North Storms, circa 1992. (Running time: 3:15)

Another participant in the Oofty Goof Band was sax player Mel McKee. Mel was a big part of Bellingham’s music scene for five decades. One of his first bands, after the Oofty Goofs, was Mel McKee and his Diplomats in the 1930s. A musician at night, to make ends meet, McKee’s daytime job was as a salesman — floor coverings, men’s apparel, even ad sales for KVOS in the early 1950s. In the 1970s, his Mel McKee and the Mel-O-Dions and the Mel McKee Orchestra were highly sought after dance bands. Mel, a lifetime member and leader in the Musician’s Union, was still performing at senior citizen events into the 1980s. In an interview with North Storms, recorded thereabouts 1992, Mel described his time with the Juvenile Band and his life in the music game.

Mel McKee from the Milton Krieger Collection on Jazz in Whatcom County. Center for Pacific NW Studies, Western Libraries, Archives & Special Collections, Western Washington University. Interviewer North Storms, circa 1993 (Running time: 3:00)

Einar Moen and Mel McKee, the last remaining members of Kessler’s Oofty Goof Band, passed away only 20 days apart in May 1994. Moen was 88 years of age and McKee was 83. Moen and McKee both turned their youthful exuberance for music into outstanding careers as professional musicians navigating the music scene in Bellingham and Whatcom County.

Oofty and Goofty Lived

The Bellingham rendition of the “Oofty Goof Frolic” had titular characters who, by no surprise, went by the names Oofty and Goofty. The female stars were chortling Whatcom High School students Ione Roll (Oofty) and her cohort Marion Bodiker (Goofty). The girls sang silly songs while Roll strummed her ukulele and Bodiker plucked at her banjo. After they graduated from high school, the girls married their boyfriends and, with her spouse, Ione Roll moved to Riverside, CA and Marion Bodiker and her husband ended up in Sunnyvale, CA. Roll (L) passed away in 2000 at age 89. Bodiker (R) passed away in 1971 at age 59.

Kessler’s Golden Year

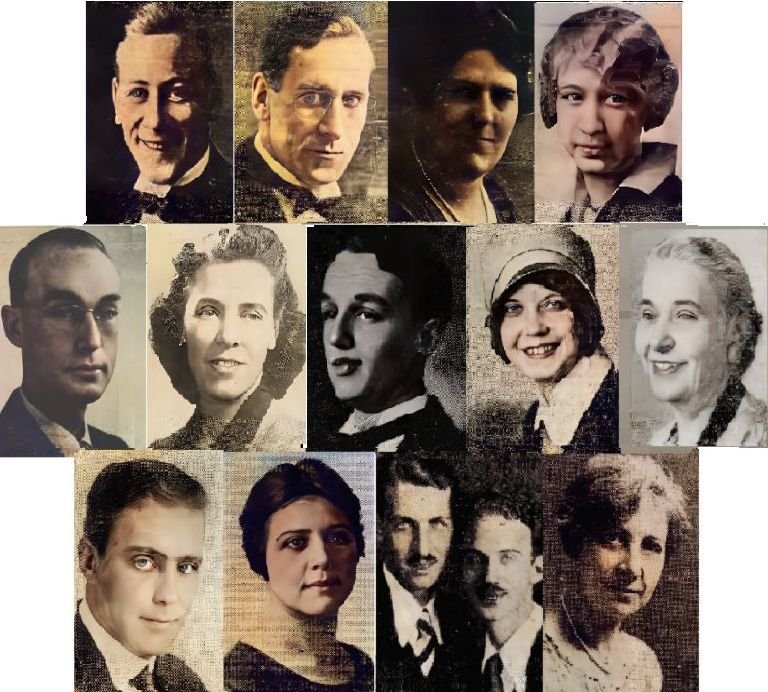

Shortly after the move to Bellingham, in keeping with Lou’s plan to offer more live in-studio entertainment, he maintained a roster of more than two dozen staff artists. In addition to the live on-air performances, the KVOS talent often appeared at recitals, dances, church events and before service clubs and fraternal organizations. In the late 1920s, the Bellingham Herald published a number of photos of the best known of the KVOS staff artists.

Still Quackin’ for Cash

In Seattle, Kessler sold airtime to the quacks pitching the miracle cure Mar-Va-Sol. In Bellingham, he had another quack paying cash. Dr. W. Delbert Darst trained as a chiropractor, but he billed himself as a “drugless physician.” He could cure the flu, rheumatism, cancer or any other malady. An expert at treating sexual disorders, he specialized in advising the ladies. Darst’s miracle cures were at best unconventional: heavy doses of sauerkraut juice, salt elixir, heating patients inside a “human bake” oven, and the tried and true process of zapping the infirm with “induced electric currents derived from fluctuating magnetic fields.” In summer 1923, lasting for less than two years, Darst was the medical supervisor and an owner of the Yoghurt Sanitarium that occupied the five-story former Fairhaven Hotel building. Any person feeling rundown, sick or injured would be admitted to the Yoghurt Sanitarium where 100% of the previously mentioned medical treatments were available. The signature cure at the aptly named Yoghurt Sanitarium came about on a daily basis as “faithful nurses” administered to ailing patients a medicinal yoghurt that Dr. Darst had cultured with his own hands in the basement of his sanitarium.

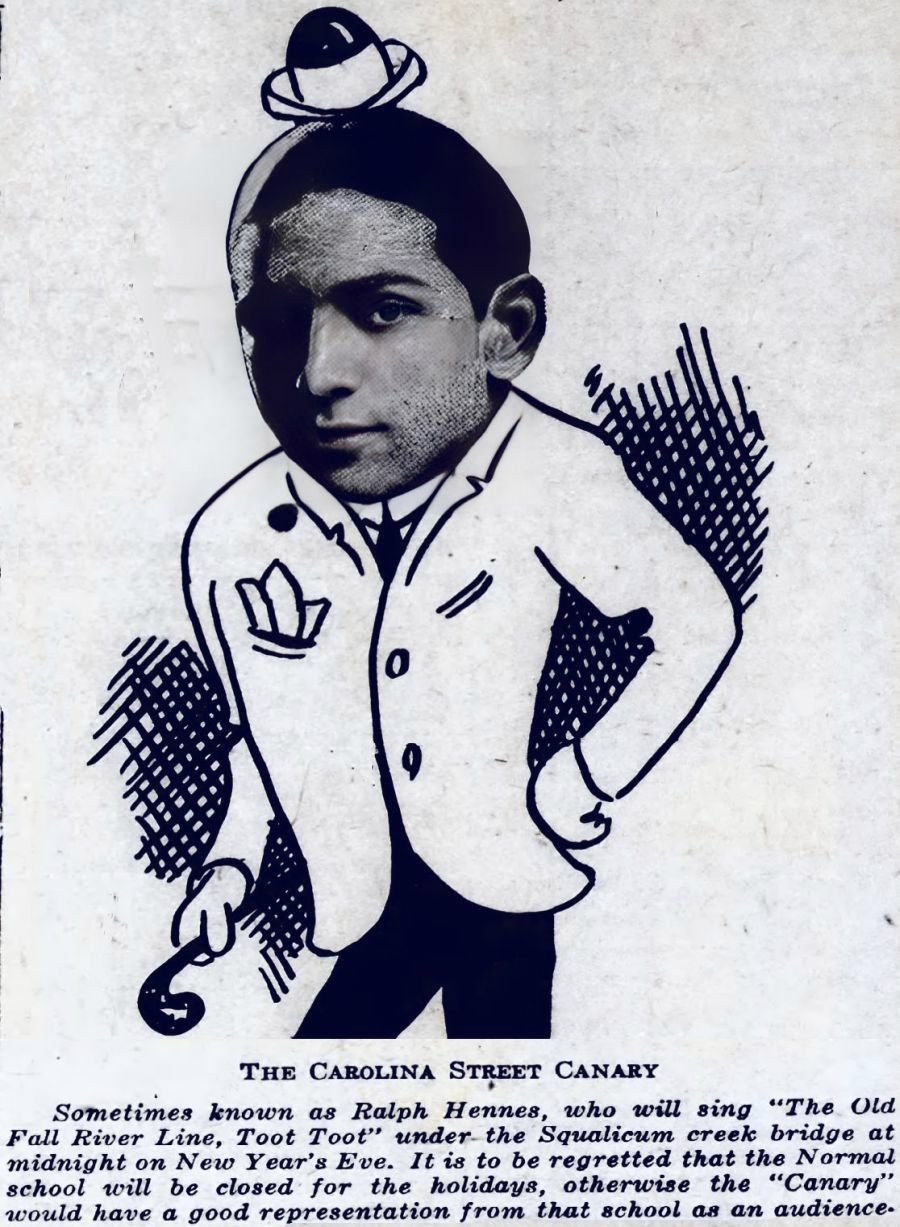

Carolina Street Canary

The dapper young man in the Bellingham Herald photo from fall 1924 was local songbird Ralph Hennes. Nicknamed the “Carolina Street Canary,” Hennes was multi-talented: a Bellingham firefighter, he was a drummer and vocalist in one of Einar Moen’s early bands, and he’d been nicknamed “Bellingham’s Singing Fireman.” In the Roaring ’20s, Bellingham adopted as its own an odd East Coast river boat song titled “On the Old Fall River Line.” A comedic tale of a steamship ride from New York to Rhode Island, the tune for some inexplicable reason became a favorite in Bellingham. Locals sang it on the Fourth of July and at various holiday festivities. Briefly it became a tradition: On New Year’s Eve, in the early 1920s, citizens gathered at midnight under the Squalicum Creek Bridge (now the Coal Mine Bridge) near the then operational Bellingham Coal Mine. The highlight came when Ralph Hennes, or another local musician, would serenade the delighted crowd with a stirring rendition of “On the Old Fall River Line, Toot Toot” (only in Bellingham was “Toot Toot” added to the end of the song’s title). There are no recordings of Hennes singing that or any other song, but Billy Murray’s original on Victor Records (No. 6 nationally in 1913) lives on. And it’s a record Lou Kessler played on KVOS.

“On the Old Fall River Line” — Billy Murray (Running Time: 2:23)

Hometown Farming

The first hometown farm show that ran on KVOS — “Farm Talk” — was presented by Harry B. Carroll Jr. The young Whatcom County extension agent reported on topics that resonated with Whatcom County’s large agricultural community. He spoke of cows, dairy farming, growing healthy strawberries and raspberries, crop fertilization and pest control. Farm reports were popular on early radio stations and Carroll was knowledgeable and respected by Whatcom County’s food producers. The Bellingham Herald dedicated lots of ink to Carroll and his farm show: This clipping ran just before Christmas in December 1927. That was only two months after KVOS had moved to Bellingham.

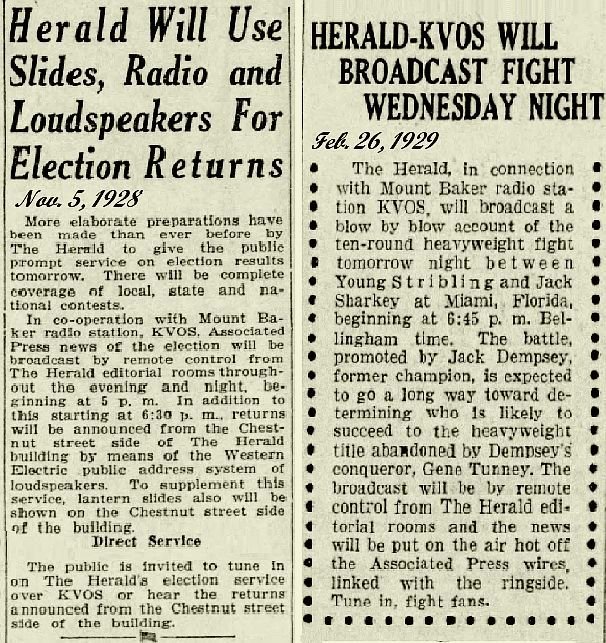

Of Presidents & Heavyweights

Lou Kessler was affable, creative and able to form mutually beneficial relationships. Under his direction, KVOS joined a small four station regional radio network that occasionally shared live programming between Bellingham, Seattle, Spokane and Portland. KVOS and the Bellingham Herald would team up to cover major national news or sports events. The Herald had access to a national news wire service and KVOS did not, so Kessler would report live from the Bellingham Herald as the news came ticking in on the old wire service teleprinter. In 1928, Cal Coolidge was leaving office and, as the election results were unfolding, GOP Presidential nominee Herbert Hoover crushed democratic candidate Al Smith in a landslide. Whatcom County got the election results first on KVOS.

In 1929, the Herald and KVOS got together on a heavyweight bout between up and coming Jack Sharkey and challenger Young Stribling. The promoter was legendary ex-heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. Kessler, again reading from the Herald’s teleprinter, simulated the blow by blow action as Sharkey pummeled Stribling to win by decision. (Sharkey was crowned World Heavyweight Boxing Champion less than two years later.) The cooperative spirit between KVOS and the Herald was short-lived. The soon to be new owner of KVOS, Rogan Jones, would have a bitter and years long feud with Frank Sefrit, the powerful editor of the Bellingham Herald.

Then KVOS Crashed

The late 1920s were financially perilous times. The Great Depression was taking its toll. In January 1929, the proprietor of the Radio Shop, a store that sold and repaired radio receivers, charged that Kessler had failed to pay a debt of $175. The shop owner petitioned for the superior court of Whatcom County to force KVOS into receivership, a legal process that protects the creditor’s interests vs. common bankruptcy that protects the debtor. The case would be heard by Superior Court Judge Edwin Gruber.

The late 1920s were financially perilous times. The Great Depression was taking its toll. In January 1929, the proprietor of the Radio Shop, a store that sold and repaired radio receivers, charged that Kessler had failed to pay a debt of $175. The shop owner petitioned for the superior court of Whatcom County to force KVOS into receivership, a legal process that protects the creditor’s interests vs. common bankruptcy that protects the debtor. The case would be heard by Superior Court Judge Edwin Gruber.

The Radio Shop’s complaint was the tip of the iceberg. When other creditors came forward, KVOS had $16,000 to $17,000 in liabilities and only $3000 to $3,500 in assets. As Kessler tried to downplay the gravity of the crisis, the Bellingham Herald incorrectly reported that out-of-town investors controlled KVOS and that was unable to resolve any financial problems. The Herald’s editors forgot that when KVOS first landed in Bellingham, they’d published a story that said Kessler had bought out all of his original Seattle area investors and his only remaining partner (holding 8% of the company stock) was the station’s chief engineer in Bellingham, Neil Brown.

With his rocky finances being the talk of the town, Lou Kessler’s reputation took a beating. In January 1929, the FRC claimed they’d received listener complaints against KVOS. The complainants reported that Kessler had canceled all live programming and he was back to playing records. Kessler said he’d run out of money and he couldn’t afford to compensate live talent. The FRC alleged that locals were ticked-off that the KVOS dial position had gone from 209.7 meters (1430 kHz) to 1200 kHz and that change made it “difficult for them to tune in better quality out-of-town radio stations.” Kessler pointed out that the recent frequency change was mandated by the FRC — not his fault. That was true: In November 1928, the feds had reassigned the dial positions of almost every radio station in the U.S. with the intent of decreasing nighttime interference and so-called “night skip.”

Those out of area radio signals that were negatively impacted in Bellingham by KVOS’ frequency change could have been signals from Seattle, Canada, California or elsewhere. With fewer radio stations 100 years ago, even low-power facilities could span great distances. For example, when KVOS was looking into a power increase to 500 watts in January 1928, the Bellingham Herald reported that 500 watts would “cover the United States.” With the public’s fondness for DXing, in the late 1920s the Seattle Daily Times regularly published an “out-of- town” radio channel guide. With night skip, and optimal weather conditions, many faraway radio signals regularly dropped into the Pacific NW.

Lost Cause

At the KVOS receivership hearing in March 1929, Judge Gruber ruled that Voice of Seattle Inc., under existing management, was insolvent. He relieved Kessler of all of his duties and responsibilities at the station. The court appointed receiver was Conrad E. Barker, credit manager at Morse Hardware in Bellingham. Barker’s role was to serve as interim station manager and to look out for the interests of the creditors. Gruber also instructed Barker to auction off KVOS to the highest bidder. That court order sealed the deal. Kessler was out; he’d lost his radio station forever. At a 1961 banquet celebrating KVOS time in Bellingham, Conrad Barker described his role when he had been the manager/receiver of KVOS radio.

Conrad Barker from the Rogan Jones Papers, “1927 Days” Center for Pacific NW Studies, Western Libraries, Archives & Special Collections, Western Washington University (Running Time: 1:35)

Sold to the Highest Bidder

Charles S. Beard was a Bellingham print shop owner, a banker and the president of the Bellingham Chamber of Commerce. He was the highest bidder at the court ordered auction of KVOS on April 15, 1929. Acting as the trustee for the majority of the stockholders, Beard represented two dozen chamber members who had either loaned Kessler money or they’d co-signed notes for him. Not surprisingly, a significant part of Beard’s $8,500 winning bid came from funds he’d collected from his fellow chamber members. The goal was to purchase KVOS and to flip it to a qualified buyer. The chamber members hoped that move would help them recoup some of their losses, but they had absolutely no interest in owning a radio station on a long-term basis.

Along Came Jones

On April 26, 1929, only 11 days after Charles Beard and chamber members had acquired KVOS, Aberdeen, WA. businessman Lafayette “Rogan” Jones paid $9000 for the station. The chamber made $500 on the quick deal. Jones was shrewd, confident, tenacious and dedicated to success as a broadcaster. On the national stage, he became one of the most influential of the pioneering early broadcasters. His story will be told in the upcoming Part 2 of this article: KVOS Radio – The Jones Era.

References (Loose Ends)

[1] Roy Olmstead the Northwest’s Most famous bootlegger

Read more about renegade cop Roy Olmstead’s bootlegging adventures by clicking HERE.

{2} Louis Kessler

Always resilient, Lou Kessler would move forward with his life, but he’d never again own a radio station. In 1930 and ’31, Kessler worked as a deputy sheriff in King County. Tasked with rounding up Prohibition era bootleggers, Lou soon resigned from that position. Claiming the liquor laws were inequitably enforced and he did not wish to be a “stool pigeon,” Kessler became an advocate for the repeal of Prohibition. In 1933, as Prohibition came to an end, Kessler got into the beverage business, selling beer and wine wholesale and retail in King County.

Louis Kessler wore many hats in his lifetime: entrepreneur, salesman, chaplain, and public employee: chairman of the State Traffic Safety Commission, deputy coroner in King County, and supervisor of the State Board of Prison Terms and Paroles. Politically aligned with the GOP, Kessler ran unsuccessfully for the state house in 1952. Later, as a protest candidate, he ran against Dan Evans in the 1964 GOP gubernatorial primary election in Washington State. Evans went on to win and be a three term governor. Louis Kessler, a military veteran who had served in the U.S. Army in both WWI and in WWII, passed away in Seattle (in 1972) at age 74.

{3} Douglas Richardson

In 1933, Douglas Richardson left radio to seek fame and fortune in Vaudeville and Hollywood. When that did not pan out, he became a puppeteer – presenting a Punch and Judy show on kid’s TV. As he reached middle age, Richardson’s alter ego Zingo the Clown appeared. Zingo sang, played the guitar, worked the puppets, performed magic tricks and threw his voice (ventriloquist). Residing in a small travel trailer in San Francisco, Zingo and his trailer often travelled to fairs and shopping centers in California, Oregon and occasionally Washington. Richardson returned to Washington when Zingo was hired as the official clown for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. Once the fair ended, Zingo stayed on as the clown for the then Seattle Center. Richardson, at 89 years of age, was still clowning around Seattle in the early 1990s. In 2004, he passed away at a care facility in Seattle at the ripe old age of 102.

The following is a complete list of Douglas Richardson’s 78 RPM shellac pressings on Columbia Records:

“Song of the Wanderer (Where Shall I Go?)” b/w “New Moon.” (Sept. 27, 1926). His second single (Feb 15, 1927) was “Every Road Leads Me Back To You” b/w “When All The World is Fast Asleep.” The third single was “Promise” b/w “I’m Looking Over A Four Leaf Clover” (Feb 15, 1927). The fourth single was “Chlo-e (Song of the Swamp)” b/w “Wond’ring” (Sept 27, 1927) and his last single was “Seven Miles To Arden” b/w “Tonight Will Never Come Again” (Sept 29, 1927).

Lost to time were any copies of Richardson’s perhaps most consequential recording: “Chlo-e (Song of the Swamp).” Released in fall 1927, the frenzied singer was searching a swamp for a woman named Chlo-e. A show tune from the musical “Africana,” Richardson’s original record wasn’t a hit. But the song got lots of attention and it became a jazz standard recorded by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Paul Whiteman and his Concert Orchestra (Billboard #7 in 1928), and many other performers. “Chlo-e” was huge (Billboard #5 in 1945) when it was recorded as a parody by Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Click HERE to watch Spike’s version of “Chlo-e,” from the movie “Bring on the Girls.”

THE END

Credits: David Richardson’s book “Puget Sounds A Nostalgic Review of Radio and TV in the Great Northwest.” “The Less Subdued Excitement: A Century of Jazz in Bellingham and Whatcom County, WA” by Milton Krieger. “Music In Washington: Seattle and Beyond” by Peter Blecha. The Whatcom County Museum Photo Archives and the Center for Pacific N.W. Studies, Archives & Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western Washington University.

Miracle elixers

April 10, 2025 at QZVX

Steven Smith says:

I always make fun of the potions sold on old radio. Then I might be watching YT and some clown will come on and tell you to throw every medication prescribed in the garbage and do what he says. I think social media is sucking in more people to quack cures than radio ever did. I have seen it happen with relatives who were desperate.

Miracle elixers

April 10, 2025 at QZVX

Jason Remington says:

The weekend radio schedules still include the medicine men with the miracle cures, plus the genius who can guide your money through the financial maze of the market with a promise of riches.

There were some real success stories in this. Mr. Hoffman lived well. Mairsy Doats. I’ll be damned! Good for him.

So, Seattle had mobs controlling the flow of alcohol, just like the mobs that ran Atlantic City and Vegas. Now, the mob in Olympia has taken control of all that.

My hat is off to Lou Kessler and Rogan Jones! KVOS tv continues to this day, although the local touch has been lost. KVOS is now run by the corporate mob.