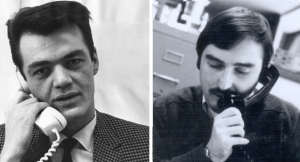

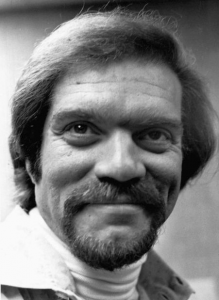

This article is a collaboration that took place over several months between Gary (Burleigh) Shannon and QZVX writer, Steven L. Smith. It is a true story of two KJR-AM disc jockeys, one of whom was a national legend and the other a prominent major market jock. The legendary figure is none other than the late Superjock Larry Lujack. The other DJ is Gary Shannon, who calls Seattle his hometown.

Lujack’s mid-sixties stint at KJR had a big impact on young Gary Shannon. Shannon wasn’t alone in his admiration for Lujack. Many famous media personalities, including Rush Limbaugh, David Letterman, and Howard Stern, incorporated elements of Lujack’s style into their own performances. Lujack was a good role model: In 1984, he signed a 12-year, $6 million contract with Chicago’s WLS. That made him one of the highest paid jocks in America. Lujack typical, sarcastic guy that he was, said of the contract: “I am not in the least bit excited.”

Lujack was a different kind of jock. He didn’t sound like everyone else. The New York Times reported: “His delivery included strategic pauses, audible paper-shuffling and grandiloquent references to himself in the third person. His style demonstrably shaped that of Rush Limbaugh, who in 1990 said “Lujack was the only person I ever copied.”

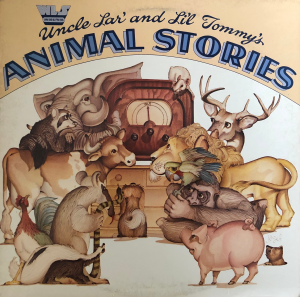

David Letterman’s televised Stupid Pet Tricks was a spin-off of Lujack’s popular feature Animal Stories. Chicago’s nationally syndicated radio and TV personality, Jonathon Brandmeier, said of Lujack: “Larry taught us that we could be ourselves on the radio.”

David Letterman’s televised Stupid Pet Tricks was a spin-off of Lujack’s popular feature Animal Stories. Chicago’s nationally syndicated radio and TV personality, Jonathon Brandmeier, said of Lujack: “Larry taught us that we could be ourselves on the radio.”

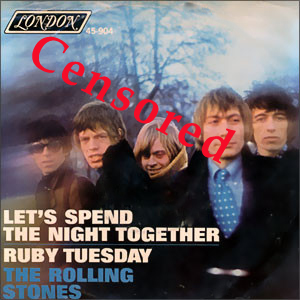

Howard Stern has far outdistanced Lujack as a “shock jock,” but in simpler days Lujack pushed the envelope as to what was acceptable on-air content. For example, at KJR he read a fan letter from a teen girl who was asking questions about French kissing. That is timid compared to the antics of today’s shock jocks, but the bit dates back to 1966. That’s the same year many U.S. radio stations crudely edited, or refused to play, the Stones’ record Let’s Spend the Night Together.

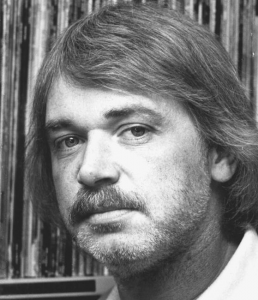

Back in Seattle, it is Gary Shannon’s opinion that another Gary — Gary Lockwood — came the closest to replicating the Lujack sound: “He had the talent to back it up and became one of the great KJR personalities.” Shannon’s view was shared by former KVI-AM deejay Peter B (Boam). Peter wrote: “Lockjaw (Lockwood nickname) and Lujack sounded so much alike they could have been fraternal, but not identical, twins.”

L ujack’s radio years in the Pacific Northwest were spent in Spokane and Seattle. However, it is impossible to profile Lujack without acknowledging his time as a radio superstar in Chicago. In fall ’66, he went from Seattle to Boston’s WMEX-AM for a short while. Then in ’67, he moved to WCFL-AM in Chicago. Four months later he was hired to work at Chicago’s WLS-AM. Lujack was a fixture at WLS for two decades. Except, he took a four-year hiatus from the station — returning to WCFL from ’72 to ’76. After leaving his position at WLS in ’87, he could be heard for several more years on stations in Chicago and New Mexico.

ujack’s radio years in the Pacific Northwest were spent in Spokane and Seattle. However, it is impossible to profile Lujack without acknowledging his time as a radio superstar in Chicago. In fall ’66, he went from Seattle to Boston’s WMEX-AM for a short while. Then in ’67, he moved to WCFL-AM in Chicago. Four months later he was hired to work at Chicago’s WLS-AM. Lujack was a fixture at WLS for two decades. Except, he took a four-year hiatus from the station — returning to WCFL from ’72 to ’76. After leaving his position at WLS in ’87, he could be heard for several more years on stations in Chicago and New Mexico.

Gary Shannon’s connection to Lujack was the impetus for this story. Let’s step back in time nearly sixty-years. In ’64, Gary was in the right place at the right time. He was a University of Washington student and Larry Lujack had recently relocated to KJR in Seattle. (Lujack had a circuitous route to KJR. He had earlier been fired from KJR’s sister station, KNEW-AM in Spokane. Therefore, before landing a gig in Seattle, he was briefly employed at KFXM-AM in San Bernardino).

S hannon vividly recalls KJRs mid-‘60s jock lineup. He refers to that era as the station’s Golden Years. From morning through night the talent was tremendous: Lan Roberts, Dick Curtis (who was also a newsman), Tom Larson (who was replaced by Big Jim Martin), Pat O’ Day, Larry Lujack, Tom Murphy, Jerry Kay and memorable newsmen Charles C. Bolland and Les Parsons. Gary believes this was the pinnacle of Seattle radio: “the station, sounded as good as any Top-40 radio in the country.” Larry Lujack agreed: “In that era, KJR was the greatest rock ‘n’ roll station that has ever existed.”

hannon vividly recalls KJRs mid-‘60s jock lineup. He refers to that era as the station’s Golden Years. From morning through night the talent was tremendous: Lan Roberts, Dick Curtis (who was also a newsman), Tom Larson (who was replaced by Big Jim Martin), Pat O’ Day, Larry Lujack, Tom Murphy, Jerry Kay and memorable newsmen Charles C. Bolland and Les Parsons. Gary believes this was the pinnacle of Seattle radio: “the station, sounded as good as any Top-40 radio in the country.” Larry Lujack agreed: “In that era, KJR was the greatest rock ‘n’ roll station that has ever existed.”

Pat O’Day, KJR afternoon drive deejay/program director, and at one time the station’s general manager, reminisced: “A broadcaster can have no greater thrill than to have had the good fortune to have created a team like this. These were phenomenal entertainers. Some went to unbelievable heights like Larry Lujack, who became the King of Chicago and the highest paid jock in the nation at the time. And yes, this team created a 30% share of all listening in the three counties. History that will likely never be repeated and what a joy to have been there.” Read more about KJR’s Golden Years, and listen to a composite aircheck, by clicking here.

Those in the know realize that KJR’s financial and ratings success in that era wasn’t dumb luck. World Famous Tom Murphy worked many major markets including Portland, Seattle, L.A. and Chicago. World Famous respects Pat O’Day: “He was the best boss I ever had. He has a great way with words. Pat’s funny and he’s a wonderful story teller. Pat had an ear for talent. He hired well and gave that talent lots of space. Last but not least, Pat was a super promoter, a man with a great mind for promotion.”

Murphy explained: “Three of Pat’s best ever promotions were: (1) Teen Fairs (Inexpensive to attend and hosted in what is now Key Arena. They featured live music, games, activities, sports equipment, clothing, electronics, and concerts by local musicians and big-name bands of national prominence); (2) All American Basketball (Jocks played faculty at local high schools. O’Day added a twist: He believed KJR should try to win games, otherwise audiences would tire of watching mostly crazy and clumsy jocks lose. He enlisted two or three ‘ringers’ — Seattle sports celebrities who could really play ball and they traveled with the team. Subsequently the ringers helped overwhelm the faculty teams and KJR usually won); (3) Hydro Races (Seafair hydroplane races were exciting and huge in Seattle. Beginning in 1970, Pat initiated and anchored the race coverage and he did so with amazing skill).”

Murphy explained: “Three of Pat’s best ever promotions were: (1) Teen Fairs (Inexpensive to attend and hosted in what is now Key Arena. They featured live music, games, activities, sports equipment, clothing, electronics, and concerts by local musicians and big-name bands of national prominence); (2) All American Basketball (Jocks played faculty at local high schools. O’Day added a twist: He believed KJR should try to win games, otherwise audiences would tire of watching mostly crazy and clumsy jocks lose. He enlisted two or three ‘ringers’ — Seattle sports celebrities who could really play ball and they traveled with the team. Subsequently the ringers helped overwhelm the faculty teams and KJR usually won); (3) Hydro Races (Seafair hydroplane races were exciting and huge in Seattle. Beginning in 1970, Pat initiated and anchored the race coverage and he did so with amazing skill).”

Gary Shannon summed-up O’Day succinctly: “Pat was an inspirational leader and most staff meetings were hilarious. He was always to the point, he didn’t pull punches when it came to criticism. When you received praise it really meant something. O’Day leads and promotes, he hires great talent, he adds great Top-40 music, and he’s supported by an aggressive sales staff. Total: Northwest radio magic. For listeners — solid gold memories.”

Getting back to our primary story, Shannon was bitten by the radio bug in the early sixties. He loved all types of music. This interest in music pointed him in the direction of radio. Heck, where else could a guy earn a living by spinning records? Gary became hooked on pursuing radio when he saw a jock at a live remote at the county fair. He decided to follow-up by visiting local stations. First he arranged a meeting with Laverne Drake, who was the respected music librarian at KVI.

Shortly thereafter, he visited KOMO-AM. Then in ’62, he met Dick Curtis at KJR and Mike Phillips at KAYO-AM. Come ‘63, Gary toured KOL-AM. In the final analysis, his favorite jocks — Larry Lujack and Dick Curtis — both worked at KJR. Shannon knew for sure that he really wanted to meet Larry Lujack!

Gary mailed a personal letter to Lujack and followed up with a phone call. His efforts paid off: Lujack suggested that Gary come by the radio station. Gary Shannon will never forget that first time he saw his idol, even though that memorable event took place more than 50-years ago.

“Lujack wore boots, black slacks, and a white shirt, with a skinny black tie — ties were mandatory apparel at KJR back then. I don’t think he had on Beatle boots. They looked more like cowboy boots, but I could be wrong. I have to mention his haircut. I thought it odd that Seattle’s hippest jock had a crew cut. Later I learned that was unavoidable, since he was serving in the National Guard. The military did not permit long hair. His vacations, while he worked at KJR, were scheduled to coincide with his obligations to Uncle Sam.”

Shannon continued: “This was real. It was 1965 and I was inside KJR and doing my best to act cool while standing only a few feet away from Larry Lujack. When he spoke, his voice sounded exactly like it did on the radio. When I arrived at KJR that day, I followed Lujack into the newsroom. I remember he sat down and read aloud his ‘rip and read’ news copy gathered from the Associated Press wire to determine which words should be emphasized. He would then underline those words. He was nice to me. I was just a rookie, my only radio experience at the time had been at a small station (KHOK-AM) in Grays Harbor County, WA. Just the same, Lujack treated me as a peer. He didn’t act like I was an annoying amateur with a litany of dumb questions.”

Gary Shannon has studied Lujack’s style: “I always wondered what it was about Larry that caught my ear in the first place. Then one day I got it. He was the first jock I had heard who sounded like he genuinely loved the music. That was apparent by the way he introduced records. “I recall his intro to a Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels’ single: ‘I dig it because it’s noisy and it’s loud!’ Then he hit the post — in this case posts (screams and then the vocal). Whether a front or back sell, Larry always found exactly the right inflection to build excitement and interest in a record.”

Like most deejays, he had his favorite records. They were interchangeably referred to as his “faves” or his “favorites.” When Larry liked a record, his listeners knew it. His intro of Ryder’s Devil with a Blue Dress On and his high-energy intro of Billy Stewart’s Summertime are examples of how good KJR sounded in the golden age of Top-40 radio.

Audio PlayerKJR intros: Cut 1- Devil With a Blue Dress On & Good Golly Miss Molly, Oct. 1966; Cut 2- Summertime, July 1966 (Run time 1:28)

Another often used Lujack expression, which was evident in the prior Mitch Ryder record intro, involved variations of: “I crave this record.” That phrase “crave” showed up in many of Larry’s airchecks. Here are other examples: The records featured are by Percy Sledge, Dionne Warwick and the Young Rascals.

Audio PlayerCut 1- KJR; Cut 2- WLS; Cut 3-WCFL: Tracks circa mid to late ’60s (Run time 1:13)

Other times Larry would emphatically declare his love for a record. The passion in his voice sounded authentic. If it was all a DJ put on, it sure didn’t sound like it. This set begins with Lujack playing one of his “faves.” The records featured are by Neil Diamond, Jefferson Airplane and Peaches & Herb.

Cut 1-KJR; Cut 2-WCFL; Cut 3-WCFL: Tracks circa mid to late ’60s (Run time 2:16)

Shannon reflected on Lujack’s distinctive delivery: “That excitement and passion he projected was an art form. I was attracted to Larry’s style and later not only his style but his substance. His timing was absolutely perfect. It always matched the tempo and intensity of the music he played. His pacing changed continually — slow to fast, then fast to slow and back again. Unlike many jocks of the time, he wasn’t repetitive or predictable. He didn’t drone on at a never changing pace. The delivery was natural, like listening to an articulate guy you might meet on the street. He was the guy next door or your buddy: down to earth, accessible and speaking directly to you. His sarcastic and at times irreverent humor was the icing on the cake.”

Lujack performed his share of strange on-air bits. He wasn’t above spoofing listeners or pulling someone’s leg. Here’s an example: If a person didn’t know the hits, he or she would probably not get the joke. At first it seems like Superjock is providing an insider’s perspective into the music business. His humorless voice sets up the listener, but anyone who was around in the ‘70s soon realizes that what Lujack just told us was pure B.S.

Audio PlayerLong Cool Woman — Hollies, WCFL 1974 (Run time :56)

In Chicago, Lujack was adept at expressing his dislike for songs he didn’t much appreciate. Shannon recalls: “I heard him give a one word intro for Bobby Helms’ hit ‘Jingle Bell Rock.’ That one word intro was strategically placed after the distinctive opening guitar and jingle. At that tiny pause, moments before the vocal began, Lujack simply said: “Heav-eeey.”

Shannon visited Lujack at KJR one other time. He was in First Phone License school and Lujack suggested that Gary should record an aircheck in the KJR production room. Another time he went to Lujack’s home, which was off Admiral Way in West Seattle and near the beach. When he arrived at the house, Lujack was prepping for his show — jotting down notes in a metal spiral notebook. Tom Murphy later told Gary that the notebook was standard KJR deejay fare — a gift supplied by Pat O’Day. Pat gave notebooks to all of the jocks to encourage them to prep for their shows.

Shannon’s best radio gig, prior to being drafted by Uncle Sam in ’66, was at Top-40 station KPUG-AM in Bellingham. Shortly after starting the job, he was told by KPUG management that Larry Lujack had recommended that the station hire him. Gary could never confirm it for certain, but he believes Lujack put in a good word for him at KPUG. The KPUG job was great while it lasted, but it didn’t last long. Gary was drafted. During basic training at Ft. Lewis, Shannon wrote to Lujack asking him to say “hi” to his buddies in the barracks. A few days later, Lujack dedicated Elvis’ GI Blues to the guys in the barracks. All of the GI’s were wholly impressed with Gary’s influence!

After Gary completed two-years in the army, he was free to pursue his own radio dreams. As it turned out, he was hired by KJRB (KJR’s sister station, formerly known as KNEW) in Spokane. Coincidentally, during Shannon’s time in Bellingham, fellow KPUG jock KIrk Wilde had introduced him to Norm Gregory. Norm wanted to enter radio and he was attending college and working at a grocery store. While Gary was in the service, Norm’s career had taken off and he had moved to KJRB. In route to Spokane to work with Norm, Gary stopped in the Windy City to visit Superjock and the late Jerry Kay, another former KJR guy. Footnote: In just three years, Norm had moved from KPUG to KJRB and on to KJR in 1969. Norm’s turn to join the big show in Seattle came first, but shortly thereafter Gary joined him at KJR.

We have identified elements of Lujack’s style that were incorporated into the personas of others. But how about the early influences on Lujack’s career? Radio veteran Bob Shannon (no relation to Gary Shannon) wrote that during Lujack’s time in Spokane, he listened to airchecks from Seattle and modeled his style after that of KJR’s Dick Curtis. According to Bob Shannon, once Lujack landed at KJR — with Curtis an integral part of the station’s on-air lineup — Lujack worked hard to develop his own memorable personality.

There was another, perhaps unexpected, influence on Lujack. Gary Shannon recalls that Larry spoke of admiring Paul Harvey and his abilities to communicate. Harvey broadcast his daily commentary from the WLS studio and Lujack had met Harvey. In 1981, Superjock told an interviewer that Paul Harvey was the only broadcaster he admired.

Audio PlayerLujack discusses Paul Harvey: Off the Record – WLS-TV 1981 (Run time 1:28)

Lujack was impressed with Harvey’s ability to fully engage 24 million listeners a week. The famous commentator did so by writing clever copy and presenting it with varying vocal inflections, pauses for emphasis, along with rustling papers and studio noise in the background. Harvey’s first radio job came along in 1933 — seven years before Lujack was born. Larry didn’t land his initial radio job until 1958. Therefore, it is not surprising that some of Harvey’s winning traits were assimilated into Lujack’s style. Lujack might have been the first Top-40 jock brave enough to incorporate pauses and paper rustling into rock radio. Deejays back then just didn’t do that: They were expected to maintain rapid-fire patter and a continuously cheery demeanor. A popular motto in radio studios was keep it “light, bright and tight.” Make no mistake about it, pauses and ambient noise were not part of that formula.

Lujack described his early days in radio to the publication Illinois Entertainer: “When I was starting out, it was common to see signs in radio control rooms that said: ‘SMILE!’ You were supposed to have a big smile on your face when you talked on-the-air and be the listener’s best friend. I thought that was fake and phony, and I just wanted to be me — a sarcastic and cynical guy. I never had a problem with ratings, yet stations kept firing me because I didn’t sound friendly enough. But I always thought it would work.”

Lujack described his early days in radio to the publication Illinois Entertainer: “When I was starting out, it was common to see signs in radio control rooms that said: ‘SMILE!’ You were supposed to have a big smile on your face when you talked on-the-air and be the listener’s best friend. I thought that was fake and phony, and I just wanted to be me — a sarcastic and cynical guy. I never had a problem with ratings, yet stations kept firing me because I didn’t sound friendly enough. But I always thought it would work.”

Frequent targets of that “sarcastic and cynical” side of Lujack included his employers, cities he lived in, celebrities, deejay colleagues, deejays across town, the music he played and his advertisers. Here are examples of Larry Lujack skewering Wolfman Jack, the City of Seattle, and Evil Knievel — a sponsor.

Audio PlayerCut 1- WCFL; Cut 2- KJR; Cut 3-WCFL: Tracks circa mid-’60s to early ’70s (Run time 2:34)

Lujack admitted that he burned bridges along the way and had lapses in judgment. There’s the rumor that he was blown-out of Spokane for inappropriate references to WWII era n–is. In 1988, KJR jock Lan Roberts mentioned that incident during a KJR retrospective broadcast.

Lan Roberts references the Spokane incident (Run time :42)

What Lujack actually said on-air was probably not as inappropriate or colorful as it seems after the story has been retold over nearly sixty-years. Long after the incident, Lujack told the publication Illinois Entertainer: “I had humongous ratings in Spokane, so I thought I could get away with anything! There was a commercial we ran for Volkswagen and it started out in German — ‘Achtung! Achtung!’ — and I thought it was funny. It reminded me of those old WWII movies. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I said something that made people think I was implying the dealership was a cover for an underground n–i movement in the U.S. It turned out the Volkswagen dealer was from Germany, he flew for the Germans in the war, and his employees were all German and they were highly offended. They were going to sue me AND KNEW RADIO, so the station fired me to get the V.W. dealer off their back.”

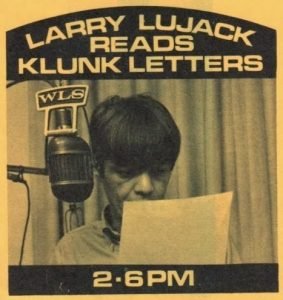

At KJR and throughout his career, Lujack got mileage out of reading letters sent in by listeners. Eventually, this regular feature earned the title Klunk Letter of the Day. In this next example, a funny bit that was mentioned previously, a teen girl is asking questions about French kissing.

Audio PlayerTalkin’ French kissing, KJR ’66 (Run time 1:10)

Jocks who worked with Lujack remember that he took those fan letters seriously. However, since Larry was not always a nice guy or polite, he would sometimes return to its sender a poorly composed fan letter. The letter would be critiqued by Lujack, and sent back with a note that instructed the sender to refrain from writing again until and unless he or she learned more about grammar, spelling, punctuation, penmanship, etc.

The most famous of Lujack’s on-air bits, and the one David Letterman imitated on TV, was Animal Stories (listen to a classic episode by clicking here). It ran on WLS from the late ’70s into the ’80s. Uncle Lar’ and his partner in the antics, Lil’ Tommy Edwards, told amusing and often bizarre tales of animals. The episodes were funny, but sometimes things didn’t turn out so well for the animals. Pat O’Day said Lujack did an early variation of Animal Stories in his KJR days, but the concept wasn’t fully developed until the Chicago years. Another of Lujack’s regular features on Chicago radio was The Cheap and Trashy Showbiz Report.

WLS-TV aired this interesting profile on Larry Lujack back in 1979.

![]()

This article on Larry Lujack’s career would be incomplete without more airchecks. Gary Shannon had this aircheck in his collection for many years. It was given to him by the late Norm Gregory. A few years ago, Gary donated a copy to a prominent online aircheck repository and it has been popular.

Audio PlayerKJR-Seattle, July 1966 (Run time 23:18)

Since we have focused on Lujack’s time in the Pacific Northwest, let’s listen to a vintage aircheck from KNEW (KJR’s sister station at the time).

Audio PlayerKNEW-Spokane, 1963 (Run time 2:24)

Readers interested in Lujack’s Chicago years can listen to a 1974 WCFL aircheck by clicking here. Or listen to a 1971 WLS aircheck by clicking here.

For the record: Superjock was born Larry Lee Blankenburg in 1940 in Quasqueton, Iowa. He was raised in Caldwell, Idaho. At 18-years of age, Blankenburg went to work at KCID-AM in Caldwell. On-air he took the last name “Lujack,” which was the surname of a pro football player he admired. His career path after that included jobs in Boise, Spokane, San Bernardino, Seattle, Boston, and on to his greatest fame in Chicago. Honors bestowed on Lujack include membership in the Illinois Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame (“It’s not Mount Rushmore.” he said upon learning of his induction) and the National Radio Hall of Fame. Lujack told The Sun-Times in 2008: “I did rock ’n’ roll radio for 30-years, it got to the point if I had to play Surfin’ U.S.A. one more time, I was gonna puke.” A heavy smoker for most of his life, Lujack died of esophageal cancer in 2013 at age 73. However, every day on radio and television stations around the country, at least in those markets where creative personalities still exist, his legacy lives on. His memory also lives on in the thoughts of once young radio personalities whom Uncle Lar’ befriended and helped along the way — just ask Gary Shannon!

Epilogue: Gary Shannon says that never in his life has he ever regretted knowing Larry Lujack. However, in retrospect if he could do it all over again, he would interject more of himself into creating his own on-air persona vs. working so hard at imitating his lifelong idol.

Credit: Sam Lawson’s Audio Vault